Defiant hits sea trials, heralding a crewless warship era

Christened on August 11, 2025, DARPA's USX-1 Defiant is now at sea proving what a purpose-built, crewless surface ship can do for cost, reliability, and scale. If trials deliver, the Navy's MUSV plan, autonomous refueling, and Tier-III yard production could accelerate within a year.

A christening that felt like a turning point

In Everett, Washington, a bottle broke across a bow that lacks a bridge. On August 11, 2025, DARPA christened USX-1 Defiant, the first full-size U.S. surface ship designed from the keel up to never carry a sailor. Now, in September sea trials, Defiant is doing more than proving an experimental hull. It is testing a thesis: that a purpose-built, no-crew seaframe can change how the Navy fights, how shipyards build, and how the fleet pays for presence at sea.

Defiant is the demonstrator for NOMARS, short for No Manning Required Ship. The 180-foot, 240-metric-ton lightship strips out everything people need and keeps everything a ship needs. There is no human passageway to route, no berthing to ventilate, no galley to feed. The result is a compact envelope that can be optimized for range, sea-keeping, electrical power, and payload volume instead of habitability. DARPA says the design should operate in sea state 5 with no performance loss and ride out worse weather safely, resuming work when the seas subside. After the at-sea demo, the plan is to turn the platform over to the Navy's Unmanned Maritime Systems Program Office, PMS-406.

What a true NOMARS hull changes

Designing a ship with zero accommodations changes naval architecture in plain ways and subtle ones.

- Deck plan: When every cubic foot can be mission, fuel, or power, you can push range and payload fraction without growing the ship.

- Manufacturing and sustainment: Without man-rated spaces, systems can be packaged as modular racks accessed from topside hatches and removable panels. Big components can be designed to slide out, not be serviced in place. That means maintenance can happen with yard tools, not a destroyer tender.

DARPA's most provocative claim is not about autonomy. It is about industry. The agency says Defiant's simplified seaframe should be buildable and maintainable in Tier-III yards that usually handle tugs, ferries, yachts, and workboats. That opens capacity that today does not touch Navy surface combatants. If NOMARS holds up in the open ocean and in Navy test events, large parts of a future MUSV fleet could be cut, welded, and turned around in regional yards near the fleet instead of competing for drydock slots alongside destroyers and amphibs.

For the Navy, that changes more than cost. It changes time. A crewed combatant is a multi-year endeavor and a highly specialized industrial dance. An unmanned workboat-class hull is a months-scale build in yards that do not need to be retooled for the task. Multiply that by dozens of yards and the calendar begins to bend.

Reliability is the hardest problem

The moment you remove sailors, you remove the people who tighten clamps, swap filters, and coax a limping engine home. NOMARS embraces that trade and then attacks it. The goal is not zero failures. The goal is graceful degradation.

- Power is distributed rather than centralized, with hybrid generation and high-capacity batteries buffering loads.

- Propulsion is modular, with major components sized and sited so a bad unit can sit idle while the rest of the ship meets a minimum performance target until the next port call.

- Onboard diagnostics must detect, isolate, and work around common faults without human intervention.

These are not small asks. But they are the ones that make NOMARS different from a converted crewed ship. You cannot retrofit graceful degradation into a platform that still assumes a sailor with a wrench can reach any given flange.

Autonomous refueling moves from demo to fleet reality

Endurance lives or dies on logistics. Refueling at sea has always been a choreography of lines, heavy hoses, and trained hands. That does not work when the receiving ship has no hands on board. In late 2024, DARPA, PMS-406, and USV Squadron One demonstrated the key steps at sea using two experimental unmanned ships, passing a lead line, mating a probe, and pumping fluid while the receiving vessel remained uncrewed. Personnel rode along as observers, not participants. That was the first on-water test of an autonomous fueling concept that Defiant is now expected to exercise in open-ocean trials.

If Defiant can repeatedly refuel without people aboard, it unlocks the obvious playbook: a smaller, cheaper ship that can stay out for a very long time, topping off from manned oilers or from other surface nodes. It also opens a distributed logistics pattern where unmanned tankers support unmanned sensors, reducing demand on high-value crewed oilers.

Payloads: sensors first, then more ambitious mixes

Defiant is a seaframe demonstrator, not a missile barge on day one. The Navy's intent for the medium unmanned surface vessel class has long started with intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance plus electronic warfare. That fits the hull and the moment. A MUSV that quietly carries passive sensors, a towed array, a signals package, and a tall mast with a relay can extend a carrier or a destroyer's reach without exposing a crew. It can also present a problem to an adversary: ignore the small ship and risk it being a decoy or a node in a kill chain, or spend a missile to roll the dice.

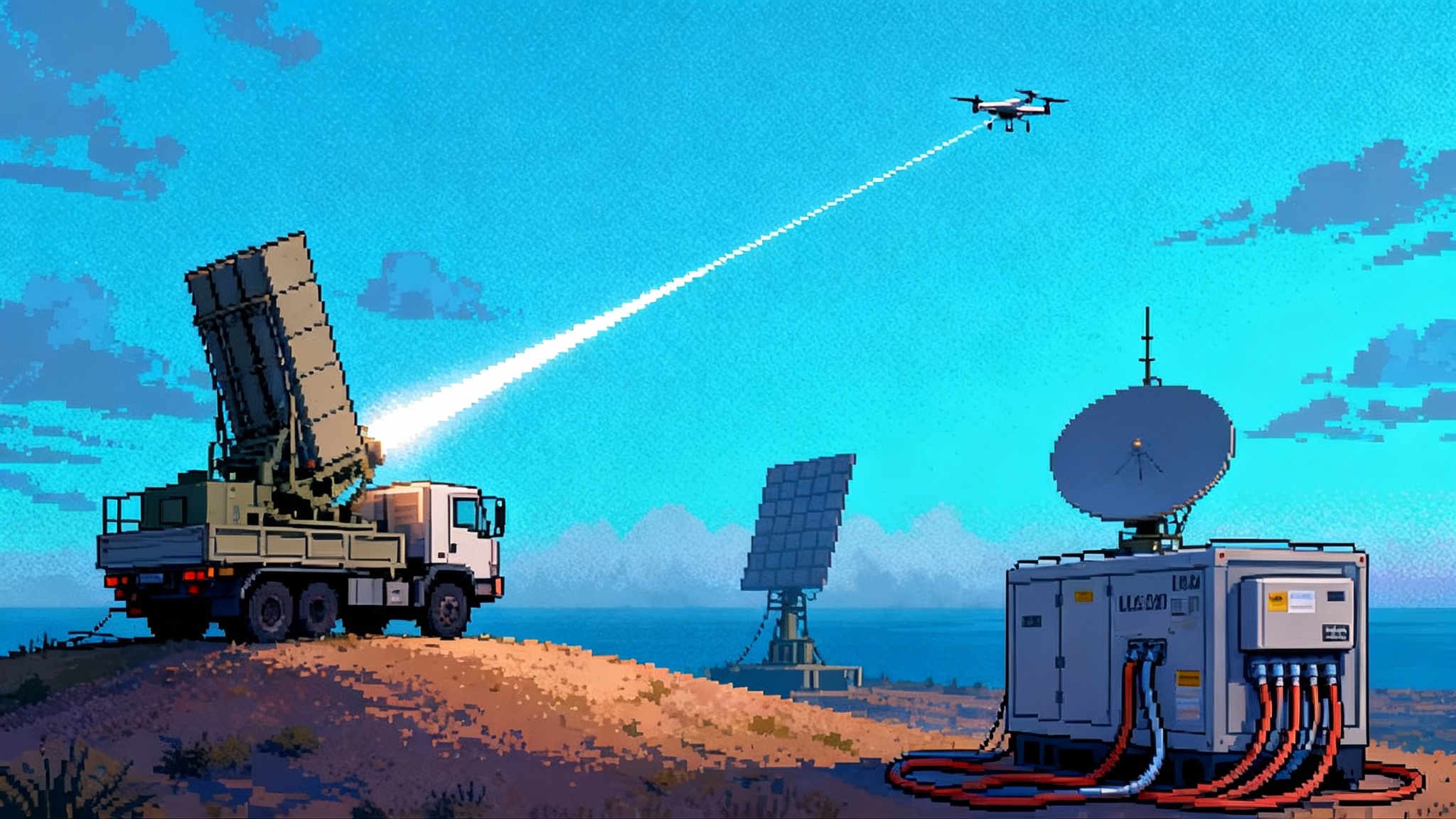

As the reliability case firms up, payload ambition will climb. A modular deck and a clean utility backbone make it straightforward to bolt on mission containers, unmanned aerial vehicle launch and recovery systems, decoys, and non-kinetic effectors. Heavy strike is more controversial. It is technically possible to mount angled launchers on a medium USV, but survivability, rules of engagement, and command and control authority for lethal force from an unmanned platform will evolve more slowly than the hardware. For context on how networks change kill chains, see the Pentagon's LEO mesh and how massed autonomy scales in Replicator moves from hype to hardware.

The EW and capture problem set

A crewless ship invites two obvious attack paths: take its senses and take the ship.

- Electronic warfare: GNSS spoofing, datalink jamming, spectrum denial, and cyber intrusion are a given in any fight with a peer. The counter is layered navigation and layered comms. An unmanned ship can blend inertial fixes, celestial updates, visual terrain or star tracking when conditions allow, bathymetric correlation near coasts, and resilient waveforms on multiple bands with burst, line-of-sight, and satellite paths. It can mission-plan to assume loss of comms and run on a playbook for hours or days if it must.

- Capture: An unmanned hull is easier to board than a frigate with a 57 mm gun and a quick-reaction team. Designers will hedge with anti-tamper enclosures, encrypted storage, remote zeroization, and the unromantic reality that a ship may be built to scuttle itself if it is about to be taken intact. The art is to do this without creating new safety hazards to nearby friendly traffic or the environment.

Expect Defiant's trial data to feed not just engineering tweaks but tactics for operating in waters where small-boat swarms, coastal militia, and opportunistic boarders are a concern. Lessons from other autonomy programs, such as autonomous wingmen lessons, will be relevant.

Transition to PMS-406 and the Navy's path to scale

One reason Defiant's debut matters is the promised handoff. DARPA says that once the at-sea demonstration is complete, Defiant transitions to PMS-406 for Navy use and further evaluation. The Navy already has a USV squadron that has taken converted commercial hulls on long runs and experimented with autonomy stacks and payloads. A purpose-built hull adds the missing piece for a proper program of record: something you can produce consistently without dragging human systems along for the ride.

If Defiant performs, the playbook looks straightforward:

- Move from one X-ship seaframe to a baseline MUSV that can be built in parallel at multiple regional yards with assured quality.

- Keep mission systems as modular kits that can be installed near the pier, minimizing yard time and maximizing commonality across batches.

- Use Fleet Introduction Teams that look more like software field service units than ship commissioning crews.

If the Navy leans in on this pattern, you get faster cycles. Instead of commissioning one multi-billion-dollar ship every few years, you could be accepting batches of MUSVs every quarter across the country, each batch carrying a slightly improved autonomy release and a targeted payload set for a theater commander's need.

The money signal that matters

The politics have started to catch up with the technology. The Senate's reconciliation package this summer boosted medium unmanned surface vessel money to a headline figure that grabbed the waterfront. Breaking Defense summarized it simply: an additional 300 million dollars brought the total MUSV spend to 2.1 billion dollars in the package, even as some crewed ship lines lost ground. See the details in this Senate reconciliation overview on MUSV funding.

What does that actually signal for the next 12 to 24 months?

- The Navy will have runway to place early production orders for purpose-built MUSVs rather than live indefinitely on converted offshore boats.

- Tier-III yards will be brought under quality and cybersecurity umbrellas and trained to Navy standards for repeatable seaframe builds. Expect a handful of pilot yards to start cutting steel within the year if trials are solid.

- Payload money will chase seaframes. EW and ISR kits will be the first to scale, followed by decoys, comms relays, and anti-drone systems useful in daily contact.

- Crewed combatant delays will push decision makers to treat MUSVs as real gap fillers. That does not mean replacing destroyers or frigates one for one. It means manned ships concentrate on command, power projection, and complex warfare while unmanned ships extend sensors, carry risk, and soak up volume tasks.

None of this is guaranteed. The reconciliation bill is a surge, not a base. The Navy still has to bake tactics, authorities, and training into a coherent concept. But in budget terms, the signal is clear. Money for MUSVs is moving from the margin to the middle of the page.

Costs, manning, and the fleet's math

A purpose-built MUSV is not free, but it avoids major crew costs across decades. Every sailor you do not have to recruit, train, billet, and deploy is real money back to maintenance and munitions. On the acquisition side, a smaller hull built in a simpler yard shifts more dollars into payloads and autonomy and away from heavy steelwork and complex hotel systems.

This also changes manning patterns. The people do not go away. They move. You need autonomy engineers, reliability analysts, payload technicians, network operators, and expeditionary maintainers who can swap a failed module on a pier in Bahrain or Guam. You need small boat crews and security teams to protect unmanned ships in port and in choke points. The fleet will look more like a cloud service with forward points of presence than a collection of identical ships with identical crews.

Industrial base: a broader bench

U.S. naval shipbuilding has lived with a thin bench for too long. NOMARS offers a way to widen it. If the seaframe is intentionally maintainable with the tools and crane capacity of a workboat yard, then Gulf Coast, Pacific Northwest, and Great Lakes yards can be part of the solution quickly. The Navy will need to certify processes, impose cyber protections, and phase work carefully, but the leverage is huge. Every new yard that can build fifty to a hundred meters of hull to a standard is a relief valve on the big yards. It also gives the Navy options to surge production regionally when theater conditions change.

Risk, regulation, and rules of the road

Crewless ships in busy waters raise legal and practical questions. Compliance with collision regulations requires a credible detect-and-avoid stack and prudent operating envelopes in traffic. Port entry and canal transits will be gated by local authorities. Use of force from an unmanned platform will be tightly bound by human command and control until policy evolves. That is healthy. It ensures early MUSVs gain trust as scouts, relays, and decoy layers before the Navy explores more kinetic roles.

Cybersecurity is the quiet risk that could dominate the whole effort. An unmanned ship is a rolling IT system with propulsors. The autonomy stack, the supervisory control links, the payload networks, and even the yard maintenance tools have to be hardened. Expect PMS-406 to impose strict configuration control, software bill of materials requirements, and red team validation as part of acceptance.

What to watch during sea trials

Defiant's September trials are not a ribbon cut. They are a checklist. The items that matter most over the next few months:

- Repeated open-ocean runs at range with logged fault management events that show graceful degradation is real and repeatable.

- A successful autonomous refueling evolution with the demonstrator itself, not just with test surrogates.

- Evidence that maintenance turnarounds can be done quickly at non-traditional yards using commercial equipment.

- Clean handoff to PMS-406 with a roadmap for early production lots, including which payloads will ride first.

If those land, the conversation shifts from whether to how many.

The bottom line

Defiant is not a toy and not a publicity stunt. It is a bet that purpose-built, no-crew ships can be reliable enough to live at sea, cheap enough to buy in numbers, and simple enough to build across a wider industrial base. The August christening and September trials are the hinge. If the data match the design, PMS-406 will have the confidence to move fast, Tier-III yards will have the work, and commanders will gain a new tool to stretch their sensor horizon and their munitions stocks.