USAF’s autonomous wingmen fly, now the hard part begins

The Air Force’s first Collaborative Combat Aircraft are moving from hangars to the sky. Here is how first flights reshape tactics and force design, what industry must scale, and which tests and policies unlock FY26 production.

First flights change the conversation

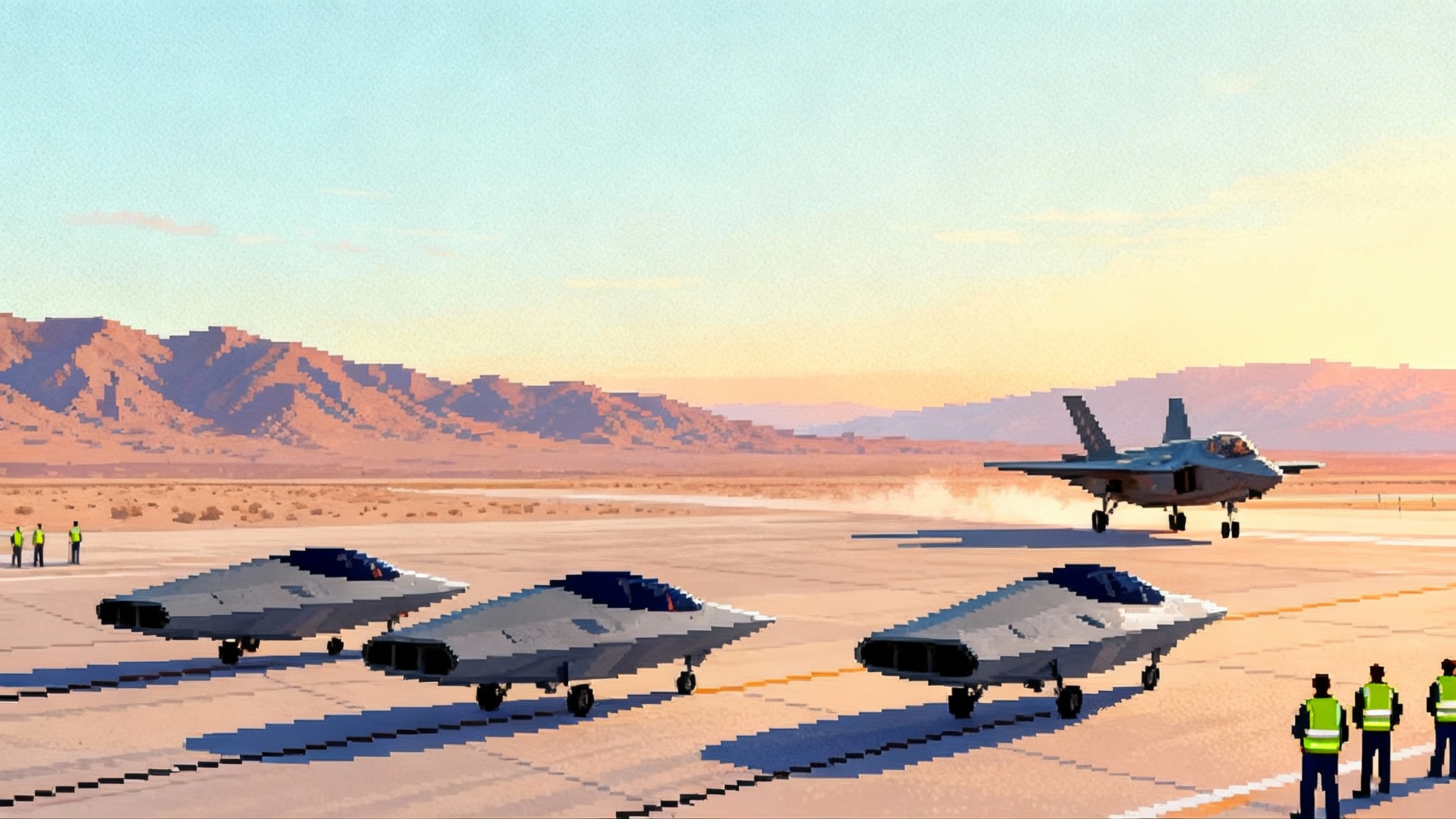

The U.S. Air Force just crossed from renderings to reality. General Atomics Aeronautical Systems’ YFQ-42A has begun flight testing, a public milestone that puts real jets and real data behind years of concept art and budget line items. The companion prototype from Anduril, the YFQ-44A, has been in ground test and is expected to fly soon. Together they represent the opening move in a program that aims to team uncrewed combat aircraft with F-35s, F-22s, and the next generation of crewed fighters.

This is not simply another test event. It starts the clock on whether Collaborative Combat Aircraft can prove they are safe, useful, and affordable at scale. The Air Force wants a production decision in fiscal 2026, and lawmakers are already asking for a concrete plan to get there. The next few months will decide if CCA becomes a fleet or another science project.

For the record, General Atomics says the YFQ-42A begins flight testing. That is the first proof point the program needed. Now the question is what the early sorties must demonstrate to unlock money, mission sets, and a credible path to mass.

What the early flights must prove

Program leaders and operators will judge these first months on data. Three baskets, in plain terms, will make or break momentum.

- Baseline airworthiness and safety margin

- Stable takeoffs, landings, and envelope expansion without surprise control law issues.

- Reliable propulsion, thermal, and power performance while carrying mission hardware.

- Predictable handling in gusts, crosswinds, and turbulence, which matters for dispersed base operations.

- Robust lost link and abort behaviors that keep the aircraft and surrounding air traffic safe.

- Teaming that actually helps the pilot

- Formation and tasking with a human lead where the uncrewed jet follows intent, not just waypoints. That means agent behaviors that interpret commander’s intent and translate it into safe, useful actions.

- Mission autonomy that adds value when the data link is pristine, and still contributes when it is degraded. Think sensor cueing, pop-up jamming, or offboard weapon employment with minimal instruction, all within rules of engagement.

- Clean interfaces in the cockpit and on the ground. Pilots must assign tasks quickly and see only what matters, not a flood of telemetry.

- Electronic warfare resilience

- Navigation when GPS is jammed. That includes alternate navigation modes and map matching.

- Communications that are low probability of intercept and low probability of detection, with graceful degradation rather than a hard fail.

- Sensor performance in clutter and deception, and the ability to keep doing a mission even when the adversary is actively trying to blind or spoof you.

Proving all three in a handful of sorties is not realistic, but early hits matter. The program must show steady progression, close the loop from flight data to software updates, and avoid long gaps between test points. That is how you build confidence in time for fiscal 2026.

How tactics and force design shift

The first obvious change is magazine depth. A flight of F-35s that brings several CCAs can carry more sensors and more weapons, with less risk to human pilots at the forward edge. The uncrewed jets can push closer to threat emitters for targeting, sprint to loft a missile, or soak up a shot that would otherwise be aimed at a crewed aircraft.

Second is disaggregated kill chains. CCAs let teams split sensing, shooting, and jamming across platforms. One aircraft sees, another jams, a third shoots. That complicates the adversary’s targeting and forces them to waste time solving for a moving puzzle.

Third is tempo. CCAs will not need the same sortie rhythm as a fighter squadron. The Air Force has already signaled this with a new Aircraft Readiness Unit model that keeps jets fly‑ready and deployable without daily pilot training sorties. That matters for manpower and sustainment. It also suits Agile Combat Employment, where aircraft hop between austere sites and rely on small teams and prepositioned kits.

Force design will evolve around those ideas. Expect detachments of CCAs aligned to fighter squadrons for operations, plus centralized software and payload teams that churn upgrades through continuous integration. Expect commanders to iterate on how many CCAs sit on each wing and which missions get priority. A missile truck package for counterair looks different from an electronic attack package, and both are different from a sensing picket that feeds the entire force.

Pressure on the industrial base

First flights move the pressure from PowerPoint to production. Two primes now have to prove they can ship airframes, software, and payloads on a schedule. The interesting twist is that the competitors pitch different strengths.

- General Atomics brings deep experience building large numbers of uncrewed aircraft with a global sustainment footprint. That helps with quality systems, supplier management, and field support. They must show they can get a new jet design out of development and into repeatable production quickly.

- Anduril emphasizes software factories, modular design, and a distributed manufacturing model that taps many smaller shops. That could scale if interfaces stay stable and quality control is rigorous. They must prove the approach yields predictable costs and consistent airframes.

Both teams will lean on a busy supply base. Small turbofans, radomes, conformal antennas, compact AESA arrays, electronic warfare receivers and transmitters, and secure datalinks are the gating items. Engines and RF components are notoriously long lead. The government’s decision to fund long‑lead parts in the next six months will tell you how serious it is about a 2026 ramp.

Open architecture is the other lever. If mission bays, electrical power, and software interfaces stay consistent, payload vendors can compete at the module level. That is how you keep costs from creeping and avoid vendor lock‑in. It is also how you can shift a CCA from counterair to EW in weeks rather than months.

What Congress wants to see

Lawmakers have been supportive, but they want receipts. The Senate’s defense policy report directs the Air Force to brief on the plan to transition Increment 1 prototypes to full‑scale production, including resources, integration with fifth‑generation fighters, data link interoperability, and an operational test plan. That formal push for a production roadmap is unambiguous. See the Senate report on CCA production plan.

In plain English, Congress expects:

- A dated schedule from now to initial operational capability, with named test gates and decision points.

- A unit cost curve that bends down with volume, not up with requirements creep.

- A contracting approach that preserves competition at the payload and software layers even if the airframe is downselected.

- A plan for how and where to base the first units, how to man them, and how to integrate with fighter wings without breaking the personnel system.

If the Air Force brings that plan and the early flight data looks solid, expect a funding surge tied to production readiness reviews and long‑lead buys in fiscal 2026.

The policy and ROE hurdles

Technology will not be the only decider. Rules of engagement and policy guardrails must mature fast enough to let CCAs do real work.

- Positive control of weapons. DoD policy still requires appropriate human judgment in the use of force. That likely means a human lead will authorize weapons release and set engagement boundaries that the autonomy agent must respect. The program will need unambiguous logs and replay to prove compliance after missions.

- Airspace integration. CCAs must meet flight safety expectations when operating near civil routes and foreign partner airspace. That pulls in sense‑and‑avoid behaviors, geofencing, and coordination with air traffic control procedures during deployments.

- Fail‑safe ethics. When communications are jammed, the jet must default to behaviors that preserve life and prevent unintended engagements. That behavior must be testable and consistent.

- Cyber and software assurance. If the fleet is updated by secure networks every few weeks, the accreditation process must be lightweight and repeatable. The test community and authorizing officials will need new playbooks that assume fast iteration rather than annual baselines.

This is doable, but it takes deliberate rehearsal in large force exercises with real fighters, real jammers, and real mission commanders. Early operational assessments should lean into that with mixed crews and honest debriefs.

Three proof points that unlock FY26

You can think of the next quarters as a funnel. If CCA delivers these three proof points by early 2026, the production case becomes hard to argue against.

- Teaming that survives friction

- A flight leads two CCAs through a dynamic intercept against a thinking adversary construct. The CCAs prosecute without perfect comms, and they do not get in the way of the crewed fighters. The pilot workload is acceptable, and trust goes up after the debrief.

- EW‑hard control and sensing

- The CCAs complete tasks with GPS degraded and with aggressive datalink jamming. Navigation stays inside safety margins and mission objectives still close. The adversary has to work harder and spend more to disrupt the team than the team spends to adapt.

- Production‑relevant builds and costs

- Airframes roll out at a drumbeat cadence with the same configuration. Software increments arrive on time and are backward compatible. The cost per tail drops in line with the learning curve. Long‑lead vendors hit their dates. The program demonstrates it can move from 2 to 4 to 8 aircraft per month without chaos.

Hit those, and the Air Force can start low‑rate production with confidence. Miss them, and the program will slip into the long‑test limbo that has killed promising concepts before.

A quick procurement playbook

If you sit in the Pentagon or on the Hill, here is a pragmatic checklist for the next 12 months:

- Freeze the external interfaces. Lock the electrical, mechanical, and software boundaries that payloads depend on. Changes after that go through a tight waiver process.

- Stage a two‑wave operational assessment. Put CCAs into an Integrated Combat Turn exercise this winter, then a Pacific‑oriented large force event in spring to validate logistics and command relationships.

- Fund long‑lead bottlenecks by line item. Engines, RF front ends, and composite subassemblies get early contract authority with clawbacks if performance slips.

- Keep competition alive. Even if you downselect an airframe, keep separate competitions for sensors, EW pods, and autonomy containers. Make the airframe a platform, not a monopoly.

- Measure trust, not only telemetry. Add pilot workload, mission effectiveness, and debrief confidence as program metrics. Those are as important as airspeed or frame drops in the autonomy stack.

What this means for operators

Pilots will get new roles. A four‑ship might come with a small herd of CCAs that must be tasked, monitored, and trusted. That requires new briefing habits, new brevity, and new displays. The payoff is more reach, more shots, and more resilience. Tactics will mature quickly once crews see that the uncrewed wingmen actually do what they are told and handle the dirtier parts of a fight.

Maintainers will manage a different rhythm. Fewer daily flights, more health monitoring, and more software change control. Some maintenance will look like aircraft, some like servers. The sweet spot is a crew that can swap a radar line replaceable unit in the morning and push a containerized autonomy update after lunch.

Commanders will get a new lever for risk. You can accept more risk forward when the platform is uncrewed, but you still care about losing scarce assets. That will push mission planners to assign the right mix of attritable and more capable CCAs to each problem set.

The bottom line

Flight test has started. That achievement removes the biggest psychological barrier for a program that aims to change how the Air Force fights. Now comes the proof. CCAs have to show they fly safely, help pilots win, and keep working when the spectrum turns hostile. They also have to show a believable path to volume without the price climbing as capability grows.

If the data is good and the production plan meets congressional expectations, fiscal 2026 can be the year the Air Force moves from prototypes to platoons of uncrewed wingmen. If not, the window closes a bit, and the program becomes another cautionary tale about ambition outpacing execution.

For now, the jets are rolling and one of them is already airborne. That puts the burden where it belongs, on flying, testing, iterating, and delivering a combat tool the force can trust.