The hidden bottleneck in Sentinel’s new-silo pivot

By opting for all‑new silos in May 2025, the Air Force shifted Sentinel from a missile program to a civil‑works megaproject. Concrete, fiber, power and EMP hardening now drive cost, schedule and risk, with GAO warning Minuteman III may have to serve into the 2050s if execution slips.

The quiet pivot that changes everything

In May 2025, the Air Force confirmed it will build brand‑new silos for the LGM‑35A Sentinel rather than convert the Minuteman III holes scattered across the Great Plains. The service said a conversion trial at Vandenberg showed unacceptable cost and schedule risk, so reusing old sites without reusing old silos is now the plan, as first reported in Air Force: build new silos.

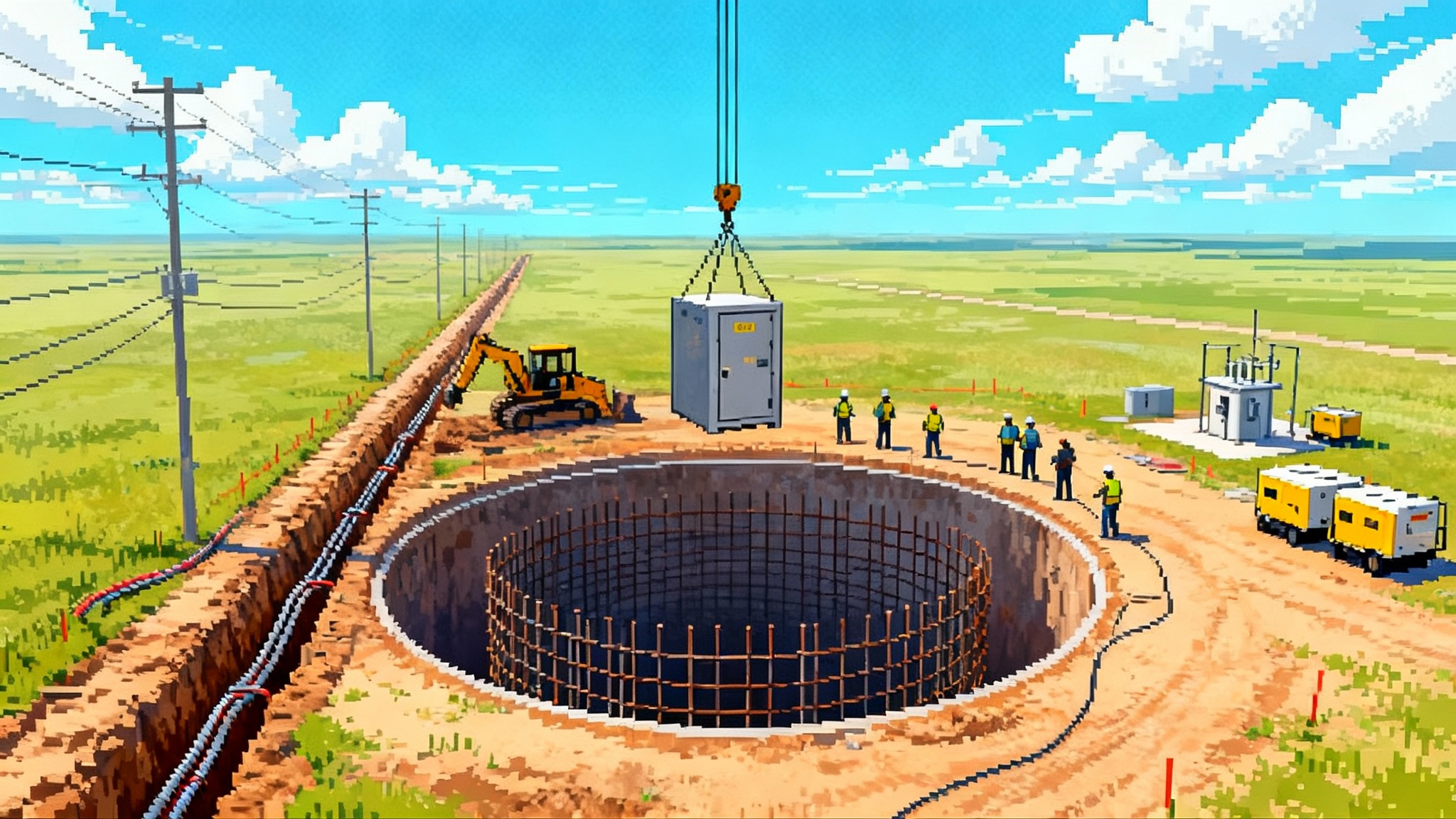

That choice sounds simple. It is not. It quietly moves Sentinel’s center of gravity from missile engineering to civil works. The program’s true bottlenecks now live in concrete, trenching, vaults, miles of conduit, new power feeds and modernized secure communications that must withstand a nuclear environment. The missile is still hard. The dirt is harder.

What changed at Vandenberg

For years the working assumption was pragmatic: dig into a 1960s Minuteman III launch facility, refurbish what you can and adapt the rest for Sentinel dimensions and loads. Vandenberg Space Force Base was the test bed. Crews opened a launch facility and began conversion, only to discover what any civil engineer dreads. As‑built drawings from the Cold War did not fully match field reality. Subsurface conditions varied more than expected. Corrosion, water intrusion paths and undocumented utilities stacked discovery on discovery.

The result was cascading change orders, schedule expansion and cost growth. Air Force officials said the Vandenberg experience validated the implications of unknown site conditions and tipped the risk calculus. With that, the service pivoted to new silos on predominantly Air Force‑owned land, often at existing sites but with clean foundations and known subsurface profiles. The logic is to trade one big risk for many smaller, more controllable ones.

The real bottleneck is in the dirt

Building an ICBM field is not just digging a hole and dropping in a canister. It is a system of systems that must survive the worst day imaginable. The civil scope looks like this:

- Silo foundations and liners: New excavations to depths exceeding 80 feet, with blast‑rated liners, shock isolation and drainage systems. Concrete quality, rebar placement and curing schedules define structural performance, which dictates how much shock the missile and its guidance can tolerate.

- Utility corridors: Sentinel requires a modern, high‑bandwidth, cyber‑resilient backbone. The legacy Hardened Intersite Cable System, largely copper, must give way to fiber in hardened conduit runs. That is trenching across ranchland and badlands, boring under roads and rivers, building pull vaults and manholes and installing redundant routes between launch facilities, launch centers and wing command centers.

- Power and backup generation: Continuous power with fault isolation is now a cyber and survivability requirement. Expect substation upgrades, higher‑capacity feeders, switched gear and distributed backup generation at key nodes. Power islands must be resilient to EMP, cyber intrusion and physical damage.

- EMP and radiation hardening: Cables, vaults, penetrations and facility enclosures need shielding and properly bonded grounds. The little things matter. An improperly terminated shield or poorly bonded splice can turn a hardened network into an antenna.

- Roads, pads and logistics: Thousands of heavy‑haul trips move rebar, cement, conduit and shelters. Winter freeze, spring thaw and permitting windows control when you can move dirt. Every weather day is a schedule day.

None of this is exotic. All of it is large. And because these tasks repeat hundreds of times over six states, small inefficiencies compound into years. The pattern mirrors other scale‑up efforts across the force, from 155mm surge chokepoints to LEO mesh communications.

What Nunn‑McCurdy exposed

When the Sentinel program tripped a critical Nunn‑McCurdy breach in 2024, the headline was cost. The number jumped about 81 percent from the 2020 estimate to around 140.9 billion dollars after the Pentagon scrub, and the schedule moved right. The more telling line was the breakdown. According to Pentagon briefings reported at the time, the majority of cost growth was associated with launch facilities, launch centers and the processes of converting Minuteman III infrastructure to Sentinel. In other words, civil construction and command‑and‑launch architecture, not the rocket itself, were the main drivers.

After recertifying Sentinel as essential, the Department of Defense told the Air Force to restructure. The new‑silo decision is a direct output of that restructuring. It removes conversion unknowns, but it also makes the program’s dependency on civil‑works throughput undeniable.

GAO’s September warning: Minuteman may have to serve into the 2050s

The Government Accountability Office’s September 10, 2025 report delivered a blunt risk assessment. It said the Air Force could need to operate Minuteman III for up to 25 more years because of Sentinel delays and rising costs. GAO also noted the Air Force lacks a comprehensive transition risk management plan and urged the service to establish one, including a schedule for a Sentinel test facility and a detailed plan for operational test launches of Minuteman beyond 2030. GAO even called out the need to address personnel and materiel implications if the United States decides to re‑MIRV ICBMs as an interim measure. See GAO’s ICBM transition risk findings.

Translated, the report says the backstop is not a slide by months. It could be decades of sustaining a 1970s weapon system, with supply chains that already strain to produce spares.

The command and control cutover is a program within the program

Moving from analog Minuteman command and control to Sentinel’s digital architecture is not just software. It is physical. Fiber replaces copper across thousands of miles. Hardened shelters and vaults get new racks, power, surge protection and crypto. Cyber readiness standards are higher. Air Force Global Strike Command officials told local audiences during spring 2025 town halls that crews plan to start digging up the legacy copper HICS runs later this decade and replace them with fiber by around 2030, while preserving missile alert coverage during construction. That cutover sequence is as delicate as it sounds, because every step must maintain a minimum number of ICBMs on alert. The broader push toward resilient, distributed networks echoes the Pentagon’s move to LEO mesh communications.

Why starting fresh can actually de‑risk

Skeptics hear “new silos” and think more cost. The Vandenberg lesson shows the opposite. Standardizing a new silo design and executing it hundreds of times, with predictable subsurface conditions, can be safer than bespoke remediation of 55‑year‑old structures. It allows industrial‑scale methods, modularization and parallel construction. It also reduces the probability of unknowns that force redesign late in the game.

The second advantage is digital integration. A greenfield utility corridor can be designed around cyber and EMP requirements from day one, rather than grafting modern fiber and shielding onto Cold War pathways that were never meant for today’s data loads. The execution mindset is similar to the disciplined, incremental approach now guiding B-21 weapons integration.

The decision timeline to watch

As of September 2025, the near‑term choices that will set the program’s fate are mostly about sequence and capacity rather than technology leaps:

- Reset baseline and phasing: The Air Force has been reworking the acquisition program baseline since recertification. Watch for updated dates on first flight test, initial operational capability and base‑by‑base conversion starts. Officials previously targeted first flight in 2026, but even that date is under reassessment as the restructure firms up.

- Test facility schedule: GAO flagged the need for a Sentinel physical security test facility to support concurrent operations of Minuteman and Sentinel. Until that exists, fielding plans remain riskier than they need to be.

- Utility corridor awards: Corps of Engineers, regional contractors and primes must award multi‑year corridor work that installs new conduits, vaults and fiber along existing routes. Expect incremental awards through the late 2020s to keep work moving across multiple states.

- HICS‑to‑fiber cutover plan: The cutover window starts to open in the second half of the decade. The Air Force must publish a sequenced plan that locks in outage windows, alternate routing and alert coverage by squadron.

- Minuteman sustainment milestones: The Air Force will need to formalize a post‑2030 Minuteman test launch plan, lock in long‑lead parts buys and decide whether to pursue any interim performance changes, including potential MIRV policy adjustments, that GAO asked the service to analyze.

Industrial‑base chokepoints, and how to actually de‑risk

The chokepoints are not mysteries. The question is whether the program will attack them early enough.

- Civil works

- Chokepoint: Silo excavation and lining capacity, specialized concrete and rebar placement crews and trenching fleets for utility corridors. Seasonal weather, right‑of‑way access and environmental mitigations can stall work.

- De‑risk moves: Pre‑qualify multiple civil primes in each missile state, publish standard work packages for silo components and modularize vaults and headworks so crews install interchangeable kits. Fund early geotechnical surveys across all fields to shrink unknowns. Stage aggregate and cement near hubs to avoid trucking bottlenecks.

- Solid rocket motors

- Chokepoint: First‑stage and second‑stage motor production slots compete with other strategic and tactical programs. Composite case production, propellant casting and cure cycles cannot be rushed. A single incident can lose months.

- De‑risk moves: Secure long‑lead materials such as carbon fiber pre‑preg and critical binders, reserve test stand windows and keep qualification testing cadence predictable. Avoid one‑off design churn that ripples into tooling changes.

- Guidance and avionics

- Chokepoint: Radiation‑hardened components, inertial measurement units and guidance computer boards are supply‑constrained. Lead times lengthen under quality‑assurance scrutiny.

- De‑risk moves: Lock stable configurations, dual‑source radiation‑hardened parts where possible and use common avionics modules across test articles and production units to reduce complexity. Keep first‑flight hardware near production standard to minimize rework.

- Secure C2 and networks

- Chokepoint: Fiber plant, crypto gear, EMP‑rated terminations and trained installers who understand nuclear hardening. Improper bonding or shielding creates rework and vulnerability.

- De‑risk moves: Standardize EMP‑rated connector kits and bonding procedures. Train a dedicated cadre of installers who travel with the project. Stand up a representative network testbed early so cyber teams can validate configurations before field deployment. Sequence corridor work to create redundancy first, then cut over.

Across all four, the pattern is the same. Fix the plan, freeze the design where you can and then feed the industrial base a steady drumbeat of work. Surge and starve, or constant redesign, will break schedules faster than any single technical risk.

What the cost narrative misses

It is tempting to frame Sentinel as a ballooning missile bill. The data and the recent pivot say otherwise. Most of the growth is in the command‑and‑launch segment and the civil works needed to carry a 21st‑century command network across 40,000 square miles. The Vandenberg trial proved that conversion risk is real. The GAO report proved that a transition without a disciplined risk plan leaves the country living on Minuteman longer than anyone wanted. The program will not be saved by a hero rocket test. It will be saved by pouring concrete, pulling fiber and closing vaults on time.

The bottom line

By choosing new silos, the Air Force traded a conversion gamble for an execution marathon. The bottleneck is no longer a bespoke missile technology problem. It is a civil‑works megaproject that must move with assembly‑line rhythm across six states while never letting the alert force dip below requirements. Get the foundations, fiber, power and hardening right, and Sentinel’s other risks become manageable. Get them wrong, and Minuteman III could be standing the watch into the 2050s.