HTV‑X1 just rewired space cargo. Why it matters now

Launched on an H3 rocket in October 2025, JAXA’s HTV-X1 reached the International Space Station with power, cooling, and hosting chops that turn a cargo run into months of lab time. Here is why that shift matters and how to use it.

A launch that resets expectations

On October 26, 2025 Japan’s new HTV-X1 cargo ship lifted off from Tanegashima on the seventh H3 rocket and cleanly reached orbit. JAXA confirmed separation and nominal flight shortly after liftoff, setting the freighter on a course for the International Space Station. JAXA confirms HTV-X1 launch. Within days, the spacecraft was captured by the station’s robotic arm in the early hours of October 30 Japan time and berthed to the Harmony module for unloading and operations.

It is tempting to file this under routine station logistics. That would miss the point. HTV-X1 is the first of a new class of freighters that do more than deliver. It is built to power, cool, and host experiments from launch to reentry, and then to keep working after it leaves the station. In practical terms, HTV-X1 behaves less like a one-and-done cargo truck and more like a box truck with its own generator, refrigeration, and workshop that can peel away from the loading dock and keep operating for months. Japan’s recent science missions such as XRISM’s Resolve X-ray map underscore how power and thermal stability translate directly into better data.

What makes HTV-X1 different

The original Japanese cargo craft, HTV Kounotori, earned a reputation for hauling big, awkward gear in its unpressurized carrier. HTV-X keeps that strength and adds a set of capabilities that shift how science and hardware can be moved and used in orbit:

- Continuous power and cooling for payloads during the ride: Experiments that need stable temperatures or steady electrical power no longer have to wait until they are inside the station to be switched on. Refrigerated lockers and powered racks can run from the moment HTV-X1 is in space.

- Late load: Items can be installed a day before launch instead of several days in advance. That shortens the cold chain and opens the door to more time-sensitive biological or material samples.

- Bigger, smarter exterior volume: Instead of hiding unpressurized cargo deep inside the spacecraft, HTV-X mounts it in a roomy open-top cylinder under the fairing. If it fits the fairing and meets safety rules, it can ride. This is practical for deployers, exposed experiments, or integrated station hardware.

- Long autonomous operations after station work: Once it departs the station, HTV-X can free-fly for months as a hosted-payload platform before a controlled reentry. JAXA’s specification targets up to six months berthed and as much as 18 months of post-ISS operations. JAXA HTV-X specifications.

The mechanism behind these upgrades is not magic. The service module carries larger deployable solar arrays, a higher-capacity battery system, and simplified plumbing and thrusters that are easier to assemble and service. The structure is lighter and the interior outfitting is more rack-friendly. All of this adds up to more usable power and volume for payloads, and a cleaner path to turn the vehicle into a stand-alone platform after it unberths from the station.

Dragon and Cygnus, compared in plain terms

If you have been following space logistics, you know the two American workhorses: SpaceX’s Dragon and Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus.

- Dragon is the only one that brings cargo home. Its capsule splashes down with scientific samples and sensitive equipment. It usually stays docked for weeks, not months. Dragon has powered lockers for internal experiments during the ride and while attached, and it has an external trunk for large items delivered to the station. Once Dragon leaves, it focuses on returning to Earth rather than acting as a long-term free-flying lab.

- Cygnus is a pressurized hauler with strong station utility. It often performs station reboosts and can stay berthed for months. After unberthing, Cygnus conducts short free-flight demonstrations or satellite deployments before a destructive reentry. It does not return cargo to Earth.

HTV-X1 occupies a new lane. It cannot return cargo, but it can do something neither Dragon nor Cygnus routinely do at scale: act as a power-rich, months-long host for experiments after it finishes station logistics. Think of it as a logistics vehicle that moonlights as an orbital testbed. That combination changes how teams plan experiments. Instead of fighting for scarce power outlets and cooling capacity inside the station or squeezing into a brief post-unberth window, users can book time on the freighter itself.

Why months-long free flight matters

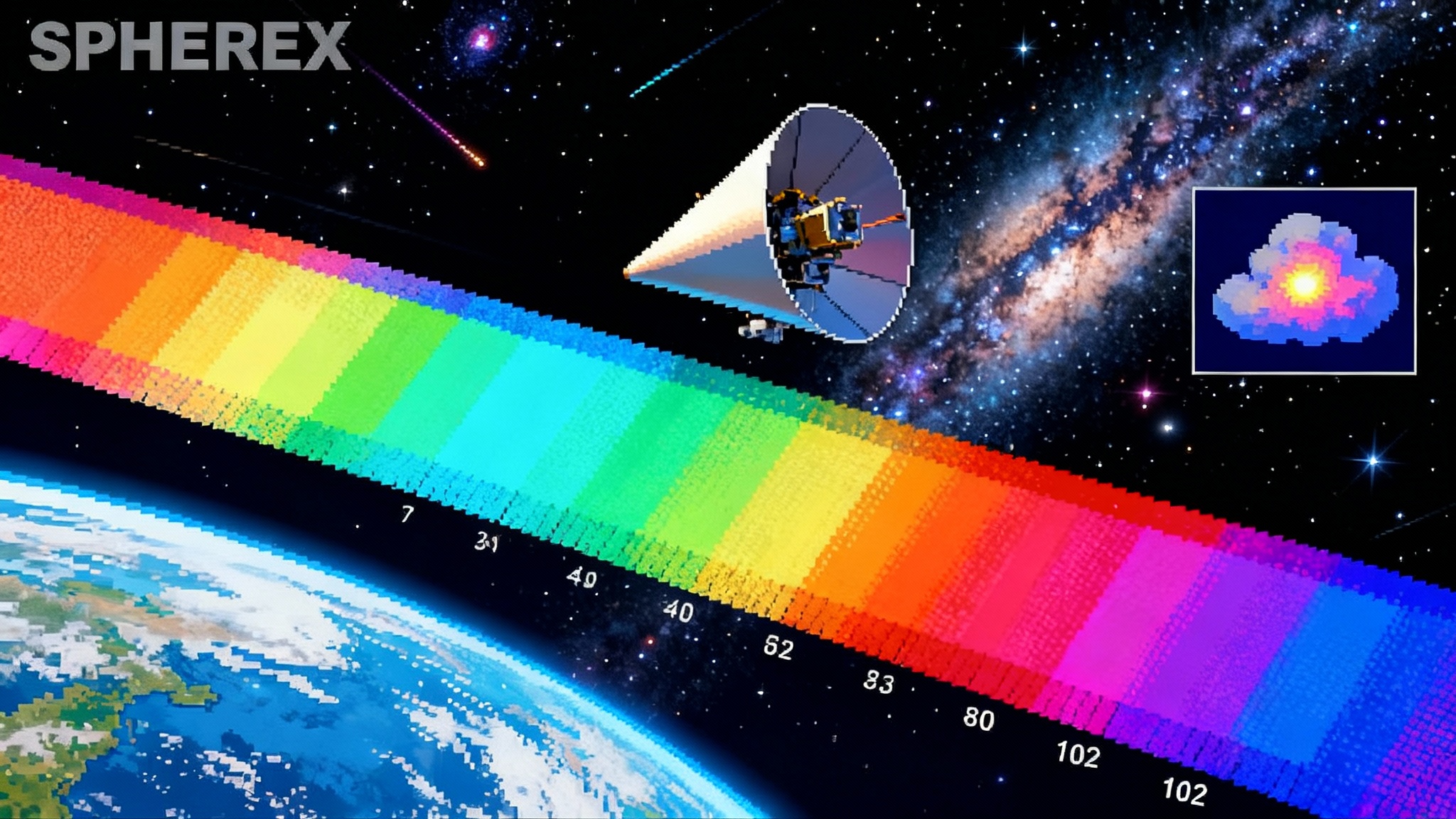

In microgravity research, time and thermal stability are everything. Many experiments are like slow-cooking recipes. Materials science needs weeks of controlled temperature to grow uniform crystals. Space biology needs steady cold chains and clean power to preserve samples or run incubations without interruption. Earth observation instruments benefit from long exposures without the thermal cycling that comes from being switched on and off.

A free-flying, power-rich freighter is like renting a quiet lab down the hall from the busy main facility. The station is a marvel, but it is also a shared house with limited closet space and a busy kitchen. By moving some experiments onto HTV-X during flight and after undocking, JAXA and partners can increase the number of power-hungry or thermally sensitive payloads that fly each year. That spreads risk and smooths scheduling. It also allows smaller teams to test avionics, sensors, or thermal designs at lower cost, because they can rent space on the already-operational spacecraft rather than build or buy a dedicated smallsat mission.

There is another advantage: proximity. An experiment can ride powered and cold from the launch pad to the station, get serviced by astronauts while berthed, and then continue operating on the same spacecraft as it departs for months of additional data collection. No re-integration. No move to a different satellite bus. That reduces complexity that often kills good ideas before they fly.

External payload support without contortions

HTV-X’s open-top external carrier is a practical fix. On many flights, large external hardware has to be packaged in complex ways to survive ascent and then extracted with robotic arms. By offering a simple, wide, rack-like volume under the fairing, HTV-X makes it easier to ship station gear, deployers, and exposure experiments. The vehicle’s higher power budget means some of those external items can be powered during flight or staged for quick activation after berthing. For teams that have struggled to fit into a capsule’s trunk or a cramped unpressurized bay, this is like moving from a hatchback to a box truck.

A better cold chain and late loading

Late loading sounds bureaucratic, but it is one of the most important operational upgrades. Moving the cargo cutoff from about 80 hours to roughly 24 hours before launch turns refrigerated and biological payloads from marginal propositions into reliable flyers. Imagine shipping fresh reagents, protein crystals, or even certain medical studies that degrade hour by hour. Shortening the countdown clock from three-plus days to one curbs losses and raises the odds that what arrives in orbit is actually useful. Pair that with powered lockers during ascent and you get a cold chain that is continuous from laboratory to orbit. That is the difference between an interesting idea on paper and a dataset you can publish.

The next 12 to 18 months: what to watch

- Platform hosting milestones: Expect JAXA and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries to exercise the free-flying mode after HTV-X1 completes its station work. The critical proof will be not just how long it can loiter, but how steadily it can power and thermally manage hosted experiments without crew tending.

- Manifest clarity for HTV-X2: Industry schedules point to HTV-X2 aiming for a 2026 launch. The key strategic question is which customers step up to occupy the new hosting slots. National space agencies will use them, but the growth signal will be commercial users booking power-hungry payloads that cannot get enough time or amperage inside the station.

- Standard interfaces: If JAXA publishes consistent electrical, thermal, and data interfaces for hosted payloads and keeps late-load options, experiment teams can design once and fly multiple missions. That is how you get learning curves and lower unit costs.

- Private station alignment: Commercial station teams will be looking for off-the-shelf logistics and hosted payload capacity while their own platforms come online. HTV-X can bridge that gap. If you run a station program, take the meeting and map where HTV-X fits your early operations.

- Insurance and certification: Continuous power and months-long operations add new risk profiles. The first customers to work with JAXA on payload assurance, contamination control, and deorbit rules will set the blueprint others follow.

Concrete actions for teams right now:

- If your payload needs more than a few hundred watts or steady cooling, request the HTV-X electrical and thermal interface documentation and begin a delta design. The retrofit cost is likely lower than building a whole satellite bus.

- If you manage a program with flight-critical samples, model the cold chain from lab to rocket fairing with the 24-hour late-load window. Use that timeline to unlock studies you previously ruled out as too fragile.

- If you operate a commercial station project, write a concept of operations that uses HTV-X hosting before your station is ready and then transitions hosted experiments to your own truss or module. This reduces schedule risk and gives early customers real data sooner.

Beyond the station: cislunar logistics and sample return legs

The most intriguing future for HTV-X is away from the station. Because the service module is power rich and designed for autonomous operations, it can be evolved into a cislunar logistics tug. In a Gateway scenario, a variant could deliver cargo to the Near Rectilinear Halo Orbit that the lunar outpost will use. The same attributes that make HTV-X useful near Earth are valuable near the Moon: dependable power for sensitive cargo, the ability to host instruments during cruise, and the ability to loiter until a docking window opens. As heavy-lift and refueling mature on other programs, such as Starship Flight 11 orbital refueling, the transport options only expand.

There is also a tactical use in sample return campaigns. Imagine a robotic mission that drops a small, sealed sample container into low Earth orbit for pickup. An HTV-X variant could be the middleman that receives, verifies, conditions, and ferries that container to a vehicle designed for Earth return. That splits the mission into legs that can be flown by different providers, consistent with NASA’s Mars Sample Return 2025 reboot emphasis on modular architectures.

A proving ground for debris-removal techniques

Japan is already a leader in debris mitigation and on-orbit servicing concepts through companies like Astroscale and through national technology efforts. HTV-X offers a large, stable, well-instrumented platform to test rendezvous sensors, proximity operations software, and capture mechanisms on extended timelines. You can mount sensors externally, power them continuously, and collect data over months. Even simple demonstrations, such as practicing autonomous station-keeping next to a representative target, would move the field forward. Because HTV-X is a cargo craft at heart, it also has a straightforward end of life. That reduces regulatory friction for tests that must end safely.

A faster, more distributed supply chain in orbit

Taken together, HTV-X1’s features point to a near-term logistics model that looks less like a single highway and more like a network of feeder roads. Here is the practical shift:

- More powered payload slots in transit and while berthed, so fewer experiments wait in line for station interfaces.

- A real option to continue operating after unberthing, so payloads can collect longer data runs without buying their own satellite bus.

- Simpler paths for oversized external hardware, so integration is less contorted and risk is lower.

That is a distributed supply chain. You can move gear when you need to, power it when you need to, and keep it running between nodes. Over the next 12 to 18 months, if JAXA demonstrates stable long-duration hosting and locks in a predictable manifest cadence, HTV-X will not just be a new vehicle. It will be new infrastructure that others can plan around.

The bottom line

HTV-X1’s launch was more than a successful flight. It was the first outing of a freighter that doubles as a laboratory. Dragon still owns the return-to-Earth niche and Cygnus still excels as a dependable station workhorse. HTV-X opens a third path: logistics plus hosting. If you build space hardware or run space research, act like this capability already exists, because it does. Design your next payload to use its power and late-load features. Plan your operational timelines to include months of free-flight data without a new satellite build. The quickest way to benefit from a better supply chain is to ship on it.