USAF uncrewed fighters enter the FY26 production race

On August 27, 2025 YFQ-42A flew for the first time. In September, the program shifted into mission autonomy trials. The U.S. Air Force’s Collaborative Combat Aircraft is now a race to an FY26 production decision and meaningful fielding by 2028.

The moment the training wheels came off

On August 27, 2025, the U.S. Air Force confirmed that General Atomics Aeronautical Systems’ YFQ-42A had begun flight testing in California. It was not a glossy concept video. It was an aircraft with a formal designation, telemetry streaming, and a real test card. The service called it a key step in a new way of buying airpower, one that prizes speed and scale. Air Force confirms first flight.

Four weeks later, during the Air, Space and Cyber conference at National Harbor, another first arrived. General Atomics leaders said they had started mission autonomy testing on the same airframe, shifting from basic envelope work to software that makes tactical choices under a human’s intent. Aviation Week also reported that the Air Force had tapped RTX Technologies to provide the YFQ-42’s mission autonomy suite, while Anduril’s YFQ-44 will use Shield AI’s Hivemind. The message was simple and consequential. Hardware is real. Software is next. Mission autonomy testing details.

If you trace lines from these two milestones to the calendar, the picture sharpens. Fiscal year 2026 begins on October 1, 2025. The Air Force has said it will make a competitive Increment 1 production decision during FY26. That is not far away. By 2028, the service wants meaningful numbers of Collaborative Combat Aircraft teamed with operational squadrons.

From prototypes to production pressure

The shift from elegant prototypes to repeatable production is the real crucible. Two teams are now in the lead for Increment 1. General Atomics brings experience building more than a thousand unmanned aircraft and a factory culture tuned for rate. Anduril brings a software native approach, modular manufacturing, and a desire to break defense cost curves. Each wants to prove it can deliver aircraft fast enough, cheap enough, and capable enough to matter in a real fight. For the broader push toward mass, see how the Replicator Reset and DAWG are reframing scale and timelines.

The decision ahead contains several nested choices:

- How many vendors for Increment 1. The Air Force could pick one for a cleaner industrial ramp, or two to keep competition alive and diversify risk.

- What rate is credible by 2028. A useful yardstick is several dozen aircraft per year that can be fielded with line units, not just test squadrons.

- How the cost is measured. Unit flyaway is only part of the picture. The service will track the cost to field a mission set, which includes autonomy progress, weapons integration, datalink gateways, training syllabi, and maintenance tools.

The FY26 call will also be shaped by the next tranche, known as Increment 2. Concept refinement contracts are expected by late 2025 or early FY26. Those awards will signal where the Air Force wants to diversify in the second wave, whether toward a stealthier airframe, a long endurance escort, or a specialized sensor carrier.

What CCAs will actually do by 2028

The goal is not a science fair. By the end of 2028, the Air Force wants CCAs to do specific jobs alongside crewed aircraft like the F-35 and the first Next Generation Air Dominance fighters. Here are the roles that are both plausible and valuable on that timeline.

- Magazine depth. CCAs carry additional air-to-air weapons so that a pair of F-35s can fight with the firepower of a small four ship. Think of two pilots directing four to six missile trucks that sprint forward, shoot on remote, and reposition.

- Sensing and sorting. CCAs push up the threat ladder first, using passive sensors to build fire control quality tracks and feed that data back to the shooters. The crewed fighters conserve signature and missiles until the picture is clear.

- Decoy and soak. Some CCAs will carry repeaters, chaff, and expendables to trigger enemy sensors and surface radars. A cheap airframe that draws a missile shot is doing a high value job if it protects a human crew.

- Stand-in jamming. A subset will carry compact electronic attack payloads to blind a specific radar during a time window. The point is not exquisite suppression. It is to open a narrow path for a strike package, then get out. For how directed-energy concepts are scaling, see microwave shields go big.

These roles do not demand a perfect artificial intelligence. They demand reliable autonomy tied to a human’s high level intent, secure datalinks that can degrade gracefully under attack, and rugged airframes that can operate often enough to give commanders options.

A 2028 scenario in three moves

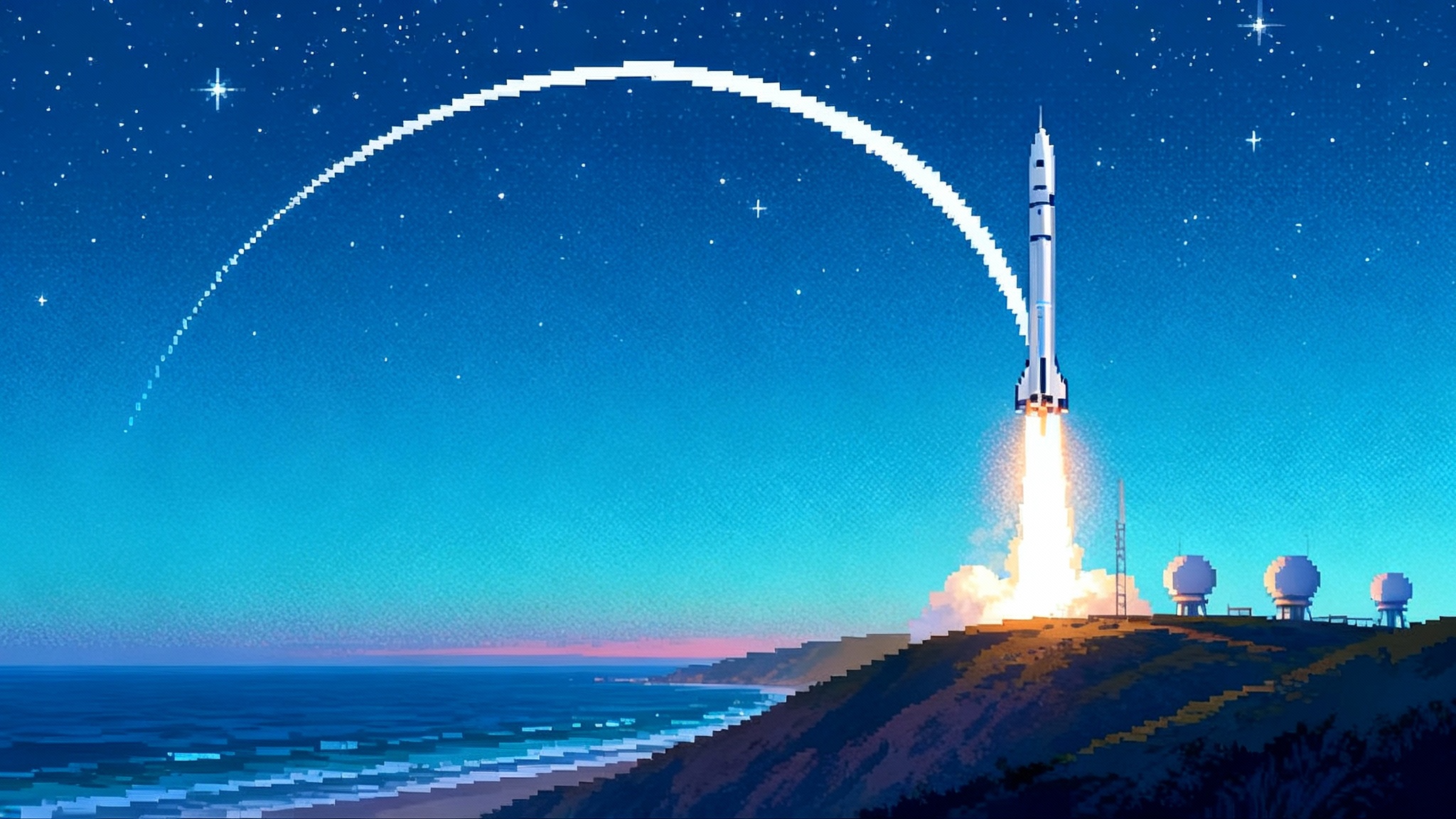

Imagine a hypothetical crisis in the Western Pacific in late 2028. A mixed package launches from dispersed sites. Two F-35As act as quarterback shooters. Four CCAs launch from a forward strip with a palletized support kit. Move one, the CCAs fan out 80 miles ahead on passive sensors, cross cueing with a standoff radar aircraft. Move two, they pass fire control quality tracks and a direct to shooter link cues the F-35s to assign shots. Two CCAs ripple pairs of missiles on command, then all four execute a drag maneuver while throwing off decoys. Move three, one CCA turns back to seed the return path with wideband jamming for 45 seconds while the rest sprint home. The pilots never cross the forward threat ring. The package lands, refuels, and repeats.

No single platform wins that fight. The team wins it by using machines for the risky parts and humans for judgment.

Autonomy that matters, not autonomy for its own sake

The September 2025 autonomy testing datapoint is important for one reason. Mission autonomy is not the same as autopilot. It is the difference between telling an aircraft to fly to waypoint Bravo and telling it to sanitize a specific slice of airspace, avoid certain emitters, and prioritize surveillance or weapons employment based on commander’s intent. In plain language, it is software that turns broad orders into action without a joystick.

The Air Force appears to be pursuing two complementary approaches. On YFQ-42, the service is integrating an autonomy suite from a major defense avionics house with deep experience in safety critical code and certification. On YFQ-44, the service is pairing a newer airframe with a fast iterating autonomy stack that has flown thousands of hours on smaller systems. The competition is not just about wings. It is a trial of software cultures.

What matters between now and the FY26 decision is steady, instrumented proof. Can the aircraft safely execute semi autonomous taxi, takeoff, and landing by early 2026. Can a pilot in a separate aircraft give intent based commands and watch the CCA choose a legal, tactically sound set of behaviors. Can the autonomy handle lost link events without surprises. These are not YouTube moments. They are test cards that decide whether a flight lead will trust a robot wingman in busy airspace.

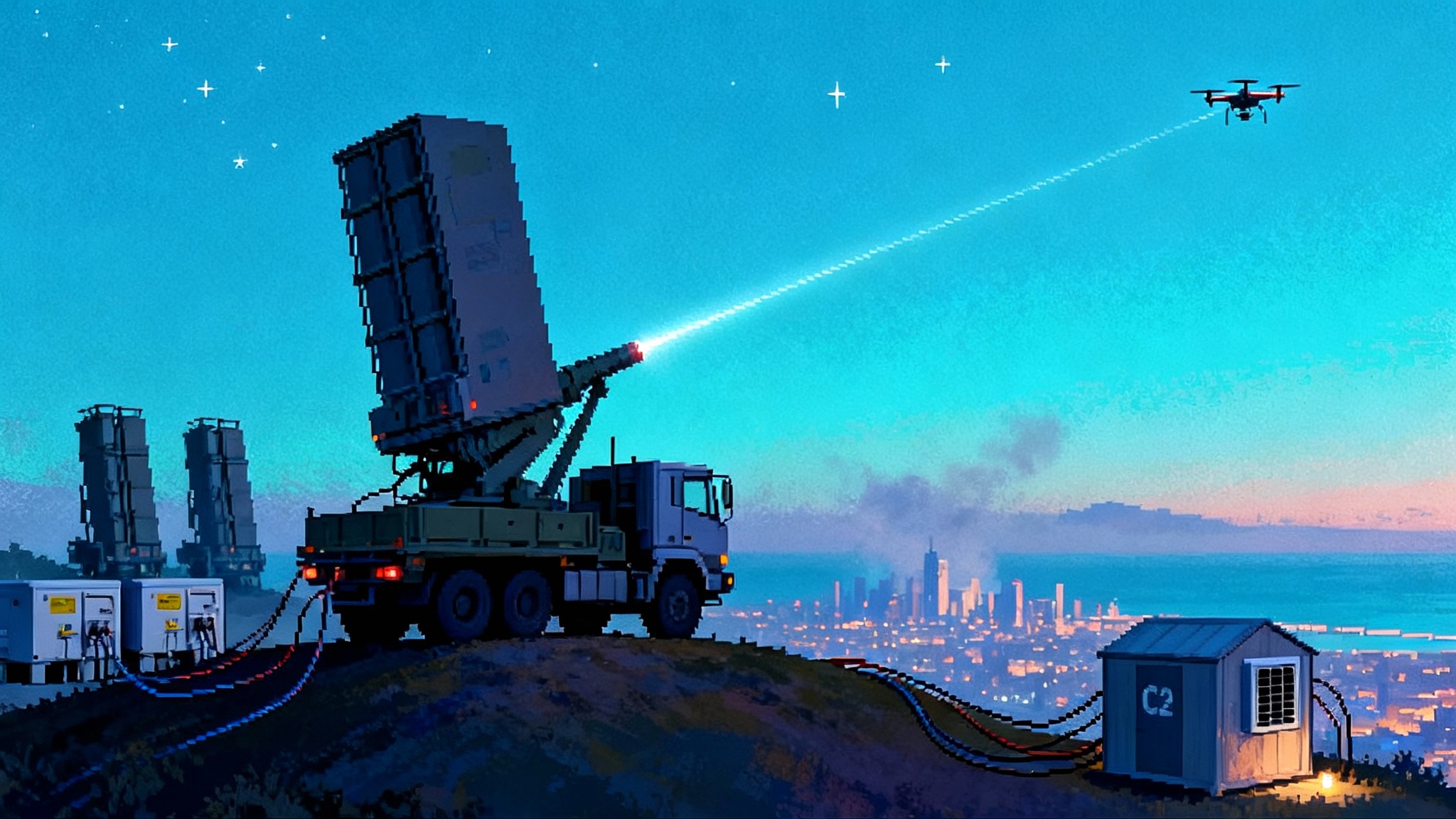

Communications and electronic warfare resilience

If the enemy can blind and mute your robots, they become targets or lawn furniture. CCAs need depth in three areas to avoid that fate.

- Jam resistant links. Expect low probability of intercept and low probability of detection waveforms, directional antennas, and power control that uses the minimum necessary energy. The goal is to be a quiet node, not a neon sign.

- Gateways and relays. CCAs will often act as translators between stealth datalinks on fifth generation aircraft and broader networks. It is better to carry the gateway forward on a semi expendable airframe than to broadcast from a high value asset. This will pair with the proliferated LEO layer as the LEO battle network arrives.

- Autonomy fallbacks. The software must continue to execute the commander’s intent if the link gets spotty. That means guardrails like preplanned fences, timeouts, and graduated return to base logic rather than brittle scripts.

A simple mental model helps. Think of the CCA as a disciplined junior officer. You give it the mission, authorities, and constraints. It communicates when it can. If it loses contact, it follows the plan, then comes home on time.

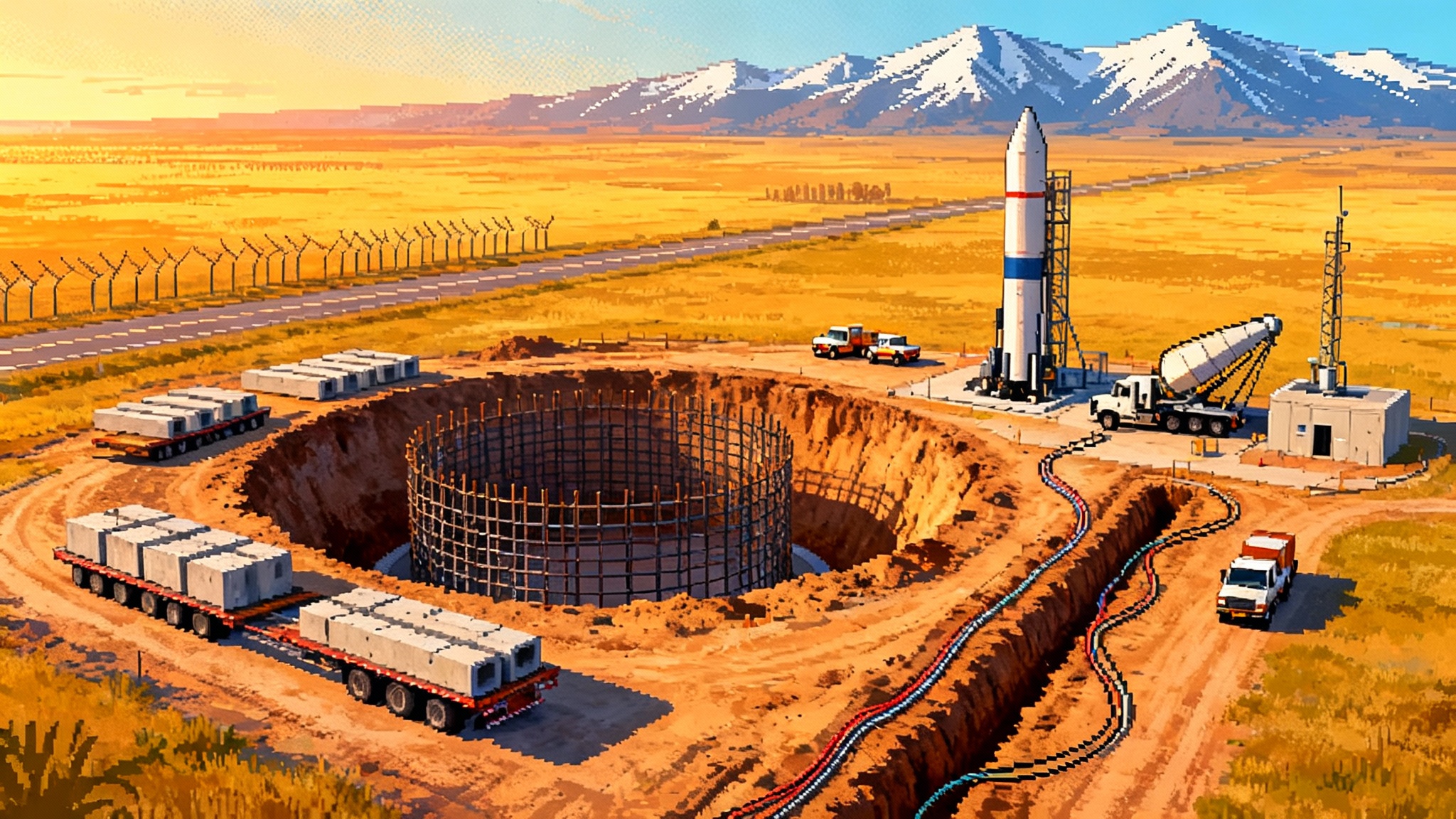

Dispersed basing without the circus

To survive long range missiles and keep sortie rates high, the Air Force is moving toward Agile Combat Employment. CCAs fit that playbook because they are simpler to support than a stealth fighter. That does not mean they are disposable. It means the logistics footprint is light enough to move often.

Picture a forward site with a single 6,000 foot runway, a small fuel bladder, a palletized maintenance kit, and a handful of specialists. A truck brings in preloaded weapons canisters. A second team sets up a portable line-of-sight relay. The CCA lands, crews swap a weapons pack, run a quick health check via built in test, and it is back in the air. The pilot directing the mission might be 300 miles away, riding shotgun in a crewed fighter or sitting at a forward mission cell. The key is speed and repetition, not perfection.

There are real limits. Jet powered CCAs need runways and fuel. They will not operate from dirt roads. They will need secure storage for crypto and sensitive modules. But compared to ferrying a crewed squadron, the footprint is small and the tempo can be high.

Anduril’s flight and the next awards to watch

Anduril’s YFQ-44A will be the next high profile milestone. Company leaders have described a semi autonomous taxi, takeoff, and landing system that they want flying on the airframe, not just on surrogates. When the aircraft takes its first flight, watch for three details. Was it remotely piloted or semi autonomous from the start. Did it meet planned altitudes, speeds, and systems checks without deferrals. Did the team publish a near term plan for expanding the envelope and moving into autonomy behaviors.

In parallel, the Air Force intends to award Increment 2 concept refinement contracts by late 2025 or early FY26. That will tell industry where to invest. If the awards emphasize longer range and stealth, expect designs that look like slim escorts. If the awards highlight electronic attack and sensing, expect stretched noses, big apertures, and power margin for payloads. The Air Force is also signaling that it wants many suppliers in the vendor pool, not just one or two giants. That increases options and keeps prices honest.

How to judge progress between now and the FY26 decision

Here is a concrete scorecard you can use as the calendar advances.

- Flight envelope growth. The prototypes should move from basic handling to clean supersonic points, then to representative loads with safe margins.

- Semi autonomous procedures. By early 2026, look for reliable remote taxi, takeoff, and landing with procedural deconfliction in mixed traffic.

- Mission autonomy demos. Expect simple, supervised behaviors first. Examples include autonomous racetrack orbits with threat avoidance, autonomous formation with a human lead, and intent based targeting drills with human on the loop.

- Sensor integration. A passive sensor suite producing fire control quality tracks is more telling than a glossy video. If the data can cue a weapon, it matters.

- Weapons workups. Before live shots, watch for captive carry tests and separation trials with telemetry pods. A clean separation campaign is a sign the design is maturing.

- Airworthiness releases. A broader release that allows operations outside a single test range is a good indicator that reliability and safety cases are convincing.

- Reliability and cost curves. The most revealing briefings will show mean time between failures climbing and maintenance hours per flight hour falling. If those curves bend the right way, production risk falls.

The bottom line

Late summer 2025 turned Collaborative Combat Aircraft from a talking point into a race. The YFQ-42A’s first flight on August 27 put metal in the air. The start of mission autonomy tests in September turned attention to the heart of the concept, which is software that can carry out a commander’s intent amid jamming and friction. The calendar is unforgiving. A production decision arrives in fiscal 2026. By 2028 the Air Force wants CCAs teaming with F-35s and the first Next Generation Air Dominance jets in meaningful numbers.

If you want a single test of whether the promise becomes reality, ask this. Will a flight lead in 2028 trust a pair of uncrewed fighters to fly 80 miles ahead, build a targeting picture, and shoot on command while the humans stay in the safer part of the fight. Everything that matters flows to that point. The hardware is catching up. The software is on the field. The production lines are being tuned. Now the service and industry must show that the new playbook can repeat on schedule, at scale, and in contact with an adversary that gets a vote. That is how CCAs will reshape air superiority, not as a slogan, but as a set of tactics that work when the air is crowded and the clock is running.