Typhon in Japan: Land-based Tomahawk and SM-6 change the game

A U.S. Army Typhon battery just touched down at MCAS Iwakuni, putting ship-killing SM-6 and Tomahawk missiles on Japanese roads. Here is how mobile Mk 41 launchers plug into the kill web, survive in the archipelago, and reshape allied deterrence.

The debut that signals a new phase

In mid-September 2025, a U.S. Army Typhon battery parked on the tarmac at Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni for Resolute Dragon 25. It was the system’s first appearance on Japanese soil, a visible reminder that long-range maritime strike is no longer only a Navy or Air Force story. The Army’s 3rd Multi-Domain Task Force brought the launcher forward for the exercise as part of a broader U.S.–Japan effort to thicken sea denial along the First Island Chain. Reporting ahead of the event confirmed the Army would deploy Typhon to Japan for September drills, and the unveiling in Iwakuni followed through on that plan.

Why it matters is simple. Typhon is a mobile launcher built around strike-length Mk 41 cells. That means it can fire Tomahawk for deep land-attack and maritime targets and Standard Missile 6 for anti-ship and anti-air roles. Park it anywhere with a good road or quay and it becomes a joint fires node that can talk to Navy and Air Force sensors and shooters. In a theater defined by distance and ocean, putting those magazines on land complicates any adversary’s calculus.

What a mobile Mk 41 adds

At its core Typhon adapts the Navy’s vertical launch ecosystem to a ground chassis. Each launcher packs a four-cell module in a standard 40-foot container, with a battery command post, communications, and power vehicles to match. The missiles are familiar. Tomahawk provides long-reach precision strike against fixed and relocatable targets at theater ranges. SM-6 brings a multi-role profile that includes anti-ship shots cued by offboard sensors and an air-defense option against cruise missiles and aircraft. Because the cells are strike length, the Army inherits the Navy’s growth path for future variants and seekers without inventing a new missile family.

Two practical advantages flow from that choice:

- Common logistics with the fleet. Spares, test gear, software loads, and handling procedures already exist.

- Battle management compatibility. The message formats that steer Tomahawk and SM-6 are well understood by Aegis and other joint systems, shortening the path to integration, as NATO’s IBCS plug-and-fight for NATO experience underscores.

How Typhon plugs into the kill web

The joint idea is straightforward. A distributed set of sensors finds a target and refines its track quality. That picture is shared across multiple data links and mission networks. A distant shooter takes a shot with a weapon that can accept in-flight updates, and any member of the team can provide the last known good target data.

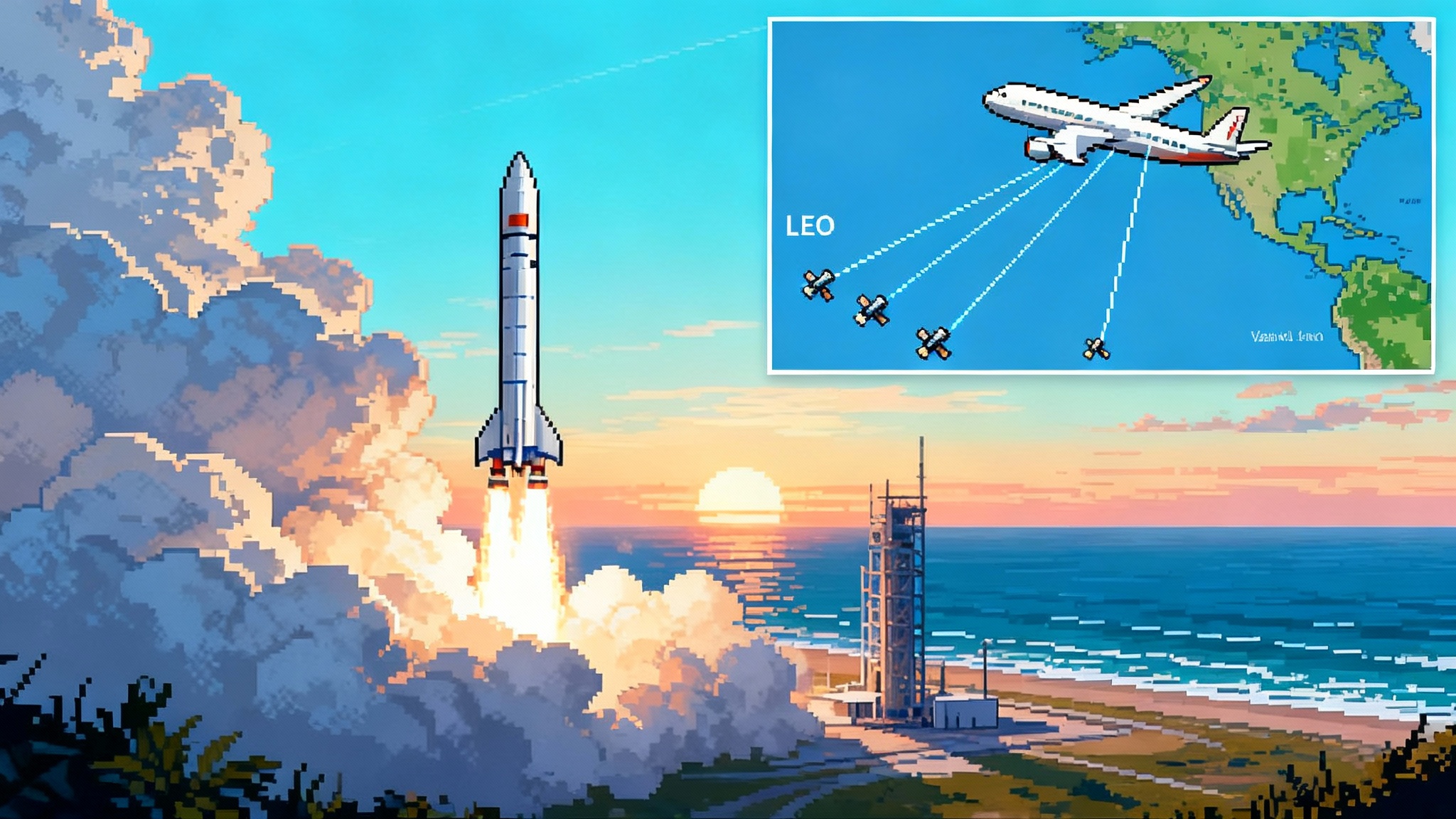

Typhon is designed to fit into that flow. Battery crews receive target data via joint tactical data links and Army fires networks and generate a fire mission that can be cleared at the appropriate echelon. Because Tomahawk and SM-6 are already integrated with Aegis, Cooperative Engagement, and other Navy constructs, the land battery can accept cues from P-8A patrol aircraft, E-2D airborne early warning, F-35 sensors, Aegis destroyers, and Joint ISR nodes. Improvements to fighter avionics like F-35 TR-3 combat clearance matter here, as do space-layer transports where SDA LEO mesh rewrites kill chains.

A recent demonstration showed what the anti-ship side of that kill web looks like with land-based launchers. In July, the Army’s 3rd MDTF conducted the first Typhon live fire outside the continental United States during Australia’s Talisman Sabre 25, successfully sinking a maritime target. The event validated combined targeting, command and control, and the mechanics of launching SM-6 from a road-mobile Mk 41.

Survivability on roads and at ports

If a system is easy to find it will not last. Typhon’s answer is mobility, footprint discipline, and deception:

- Mobility and camouflage. The launcher resembles a civilian container on a standard heavy truck until it emplaces. Batteries disperse across secondary roads, quarry lots, and small ports, using hides with overhead cover plus decoys that mimic thermal and radio-frequency signatures.

- Shoot-and-scoot timelines. Short setup and displacement cycles help crews fire and move before overhead sensors can cue fires.

- EM resilience. Emissions control, burst transmissions, and alternate communications paths keep the battery connected when primary networks are jammed or cut. Passive measures such as multispectral nets, false emitters, and dummy containers raise the cost of targeting.

In Japan’s southwest archipelago the map favors the defender. Dozens of islands and hundreds of kilometers of coastline create options to stage at a large base like Iwakuni, then move by road or short sea lift to operating sites that are hard to predict. The battery can cycle between hides and short-duration firing points and depend on partners to keep the sensor picture fresh while it keeps its radios cold.

Logistics and the maritime transport trial

Getting a launcher into position is as important as what it can shoot. The Army and its partners have been quietly validating how to move Typhon by sea and air so it can flow across the theater without telegraphing every move. In November 2024, an Indo-Pacific oriented unit loaded a Typhon module onto a chartered vessel at the Port of Tacoma. The event, documented in early January 2025, was a risk-reduction drill to prove roll-on loading, sea lashings, port handling, and the choreography among port officials, Military Surface Deployment and Distribution Command, and industry. In plain language the team was rehearsing how to move the launcher around the First Island Chain on short notice using civilian shipping.

Air mobility remains part of the playbook for rapid insertion, but in a sustained campaign most movement will be over water and road. That is where the maritime validation matters. It confirms the launcher can move discreetly between commercial ports and then disperse down coastal roads the way a standard container would. In the Western Pacific, where every pier may be a potential target, the ability to pulse a battery through several minor ports instead of a single major hub is a genuine survivability advantage.

Command and control with Japanese forces

The debut at Iwakuni coincides with institutional changes that make joint employment easier. Japan stood up a permanent Joint Operations Command in March 2025 to unify Ground, Maritime, and Air Self-Defense Forces and to streamline combined operations with U.S. forces. In parallel, the United States began upgrading U.S. Forces Japan into a true joint force headquarters with more operational authorities to act as JJOC’s day-to-day counterpart. Those moves shrink decision loops and make it simpler to pass targeting data, deconflict fires, and assign magazines regardless of whether the missile leaves a ship, aircraft, or a road-mobile launcher.

On the ground the Army’s 3rd MDTF connects through its Land Effects Coordination processes to align with Japanese formations that command coastal defense units and anti-ship missile regiments. The practical tasks are mundane but decisive: shared airspace control measures, fire support coordination lines, and common tools for target vetting and weaponeering. The more routine that becomes in exercises, the more credible the posture looks to an adversary.

Politics and law in Japan and the Philippines

Deterrence only works if it can be sustained politically. In Japan the system’s presence sits within a long-standing alliance framework and a Status of Forces Agreement that governs U.S. basing and training. Tokyo’s 2022 strategic documents endorsed a counterstrike capability, and Japan is procuring longer-range missiles of its own. That said, local communities matter. Bringing a land-based strike system to Yamaguchi Prefecture for an exercise will always trigger questions about safety, noise, and escalation. Transparency with host municipalities and a clear exercise schedule are part of maintaining consent.

In the Philippines, Typhon’s first overseas deployment arrived in early 2024 under the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement, which allows rotational U.S. access at selected sites. Manila has been explicit about the deterrent value of forward U.S. fires, even as Beijing criticized the move. The system was not live fired there in 2025, but its continued presence highlighted the legal flexibility to stage and move such capabilities under EDCA and long-standing mutual defense arrangements. As in Japan, the political logic is to keep deployments rotational and exercise-driven while building capacity in the host force.

What allies see and want

Typhon’s performance has triggered allied interest well beyond the Pacific. Germany publicly signaled its intent to pursue the system in mid-2025 as Berlin rebuilds long-range strike options and looks for a common magazine that can plug into NATO networks. The attraction is the same: a road-mobile launcher that fires Tomahawk and SM-6 gives a land formation the ability to hold high-value targets at reach and contribute to sea denial without building a new missile ecosystem from scratch. Expect other allies to study similar paths or to ask for rotational access to U.S. batteries as an interim step.

The PLA playbook against Typhon

No capability arrives in a vacuum. The People’s Liberation Army will move quickly to counter a land-based maritime strike threat inside the First Island Chain. Expect:

- Sensor and shooter suppression. Space and airborne ISR to find launchers, long-range rockets and cruise missiles to service firing points, and electronic warfare to fracture the data links that feed the kill web.

- Cyber and influence operations. Campaigns against logistics and mission systems, plus information operations aimed at host communities when batteries exercise near ports and towns.

- Operational gambits at sea. Surface groups pushing into gaps in the sensor picture, daring the joint force to shoot without perfect target data. That puts a premium on resilient, multi-path sensing from seabed arrays to small uncrewed aircraft and on exercising cross-cueing so that any sensor can close the last miles of uncertainty for a land battery.

- Early fires on key nodes. Rocket Force salvos against known bases and main supply routes to force Typhon onto small ports and tertiary roads, making mobility discipline and maritime lift rehearsals central to survival.

What changes for joint fires and sea denial

Typhon in Japan does not replace ships or aircraft. It changes the geometry of the fight. Distributed batteries create additional magazines that can be tasked from the same kill web as Aegis destroyers and P-8 patrol aircraft. They complicate any blockade plan by threatening surface groups from unexpected azimuths and add a persistent deep-strike option ashore. They also drive healthy habits: emission control, deception, joint fires rehearsal, and logistics that lean on commercial ports and roads.

The First Island Chain is a contest of time and distance. By parking Navy-class missiles on trucks inside the theater, the alliance buys both. The mid-September debut at Iwakuni shows the politics and the plumbing can support it. The July sink exercise in Australia shows the missile and the launcher deliver as advertised. The rest is steady work. More sensors in the web, more practice passing target-quality tracks across services and borders, and more routine rehearsals at ports and road junctions that make movement second nature. Do that well and a few container-shaped launchers become a strategic problem for any fleet that sails too near Japan’s shores.