Typhon Comes Ashore: Land-Based SM-6/Tomahawk Deterrence

From northern Luzon to Japan’s Resolute Dragon, Typhon launchers are moving from demo to deterrent. We break down how land-based SM-6 and Tomahawk change survivability, strike geometry, joint kill chains, signaling, costs, and the 2025 to 2027 outlook.

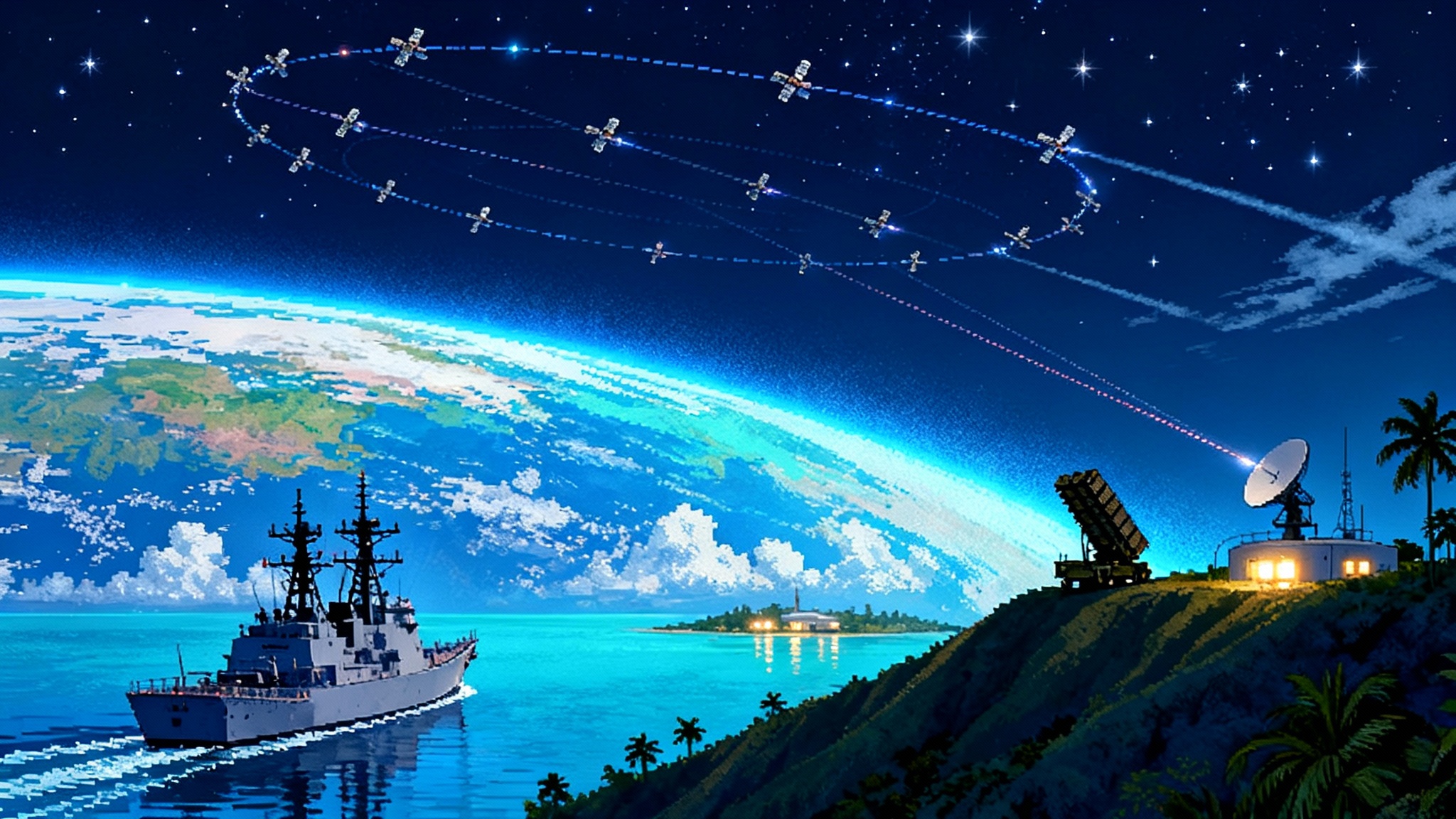

A new shore battery that changes the map

Three dates tell the story. In April 2024 the U.S. Army flew its first Typhon battery into northern Luzon, the first time the Mid-Range Capability entered the theater. In January 2025 Manila said the battery would stay and be repositioned on Luzon, signaling a shift from demonstration to presence Typhon to stay in Philippines. In September 2025 the Army publicly revealed Typhon in Japan during the Resolute Dragon exercises at MCAS Iwakuni, underscoring the alliance’s new land-based strike option Typhon unveiled in Japan.

That arc matters because Typhon is not just another launcher. It is a mobile, containerized adaptation of the Navy’s vertical launch architecture that can fire Tomahawk cruise missiles and the SM-6 multipurpose missile. In practical terms, it gives land forces a maritime strike and deep land-attack tool that can be dispersed, hidden, and moved across roads and airfields inside the First Island Chain. For People’s Liberation Army planners who have long leaned on anti-access and area denial concepts, it introduces a shore-based, shoot-and-scoot problem that does not sit neatly in their traditional naval or air targeting lanes.

What a mobile, land-based SM-6 and Tomahawk force does

Typhon adds three attributes that matter in the Indo-Pacific.

-

Survivability through movement and deception. Each launcher is truck mounted, road mobile, and paired with a battery operations center that can set up and tear down quickly. This enables shoot-and-scoot cycles that deny an adversary a clean kill chain. When launchers are spread across multiple sites and mixed with decoys, the attacker must expend scarce reconnaissance and strike assets on many maybes rather than a few knowns.

-

New arcs from the First Island Chain. From northern Luzon, Tomahawk and SM-6 can reach across the Luzon Strait into the Bashi Channel, a chokepoint for naval traffic moving between the Philippine Sea and the South China Sea. From southern Kyushu or the Sanyo region, those arcs can sweep the East China Sea and the approaches to the Miyako Strait. Geography becomes leverage. The First Island Chain’s ring of roads, ports, and airfields converts into a dispersed network of ground launch points that can mass effects without massing forces.

-

Integration with joint kill chains. Typhon is a node, not a standalone battery. Its missiles rely on external sensing and cueing to reach out to moving ships or specific land targets. That means the real power comes when it is fused into U.S. and Japanese sensor grids, from maritime patrol aircraft and E-2D airborne early warning, to space-based ISR and Aegis combatants. In a fast kill web, any trusted track can be serviced by any available shooter. The addition of a land shooter with maritime reach diversifies the set of options the joint force can call on when weather, enemy air defenses, or electromagnetic conditions complicate aviation and surface operations. For Japan’s maturing sensor and interceptor network, see how Japan’s SPY-7 air defense is reshaping coverage.

How it bends PLA A2/AD math

PLA anti-access and area denial concepts rest on the idea that long-range sensors, missiles, and aircraft can hold U.S. carriers, cruisers, and forward air bases at risk and thereby deter or delay intervention. Typhon introduces a new category of targets and launch geometries that force rebalancing.

-

Targeting costs rise. Mobile launchers that hide in clutter and move after brief communications windows require persistent ISR with high revisit rates. That stretches space, air, and surface sensors and dilutes the concentration of assets against big targets like runways, fuel farms, and ships. Even if the PLA detects a launcher, it must decide whether to spend a costly long-range missile on a decoy or a small truck that may already be gone.

-

Interdiction becomes a locality problem rather than a base problem. A fixed air base can be crated by a handful of ballistic or cruise missiles. A dispersed battery that can deploy across provincial roads and commercial airfields turns interdiction into whack-a-mole across dozens of localities. That favors the defender, especially when host nations assist with camouflage, concealment, and deception.

-

Sea denial from land complicates the naval picture. Anti-ship trajectories from shore-based SM-6 or Tomahawk create crossfires with allied aircraft and surface ships. A PLA surface action group transiting a strait must now consider threats from shore that can be retargeted midcourse. The ability to threaten shipping lanes and task groups without committing scarce fighter sorties or exposing destroyers reduces the defender’s risk while increasing the attacker’s planning burden. For context on Beijing’s advancing strike portfolio, see China’s new hypersonic A2/AD.

Survivability by design: shoot, scoot, and seem larger than you are

Survivability is not only about armor or hardening. For Typhon it is about mobility, emissions control, and deception.

-

Mobility. Launchers and support vehicles can be airlifted by C-17s, ferried by landing ships, and convoyed by road between EDCA sites in the Philippines or exercise areas in Japan. Rapid emplacement and displacement shorten exposure to enemy ISR and strike cycles.

-

Emissions discipline. If the battery uses brief, scheduled, or line-of-sight communications windows, it reduces the risk of geolocation by electronic support measures. Passive reception of targeting data and preplanned fire mission packages help the battery remain radio silent until the moment of execution.

-

Deception and decoys. Inflatable or wooden mock launchers, fake heat signatures, and false logistics patterns can burn adversary time and weapons. Even a small ratio of decoys to real launchers forces an attacker to overcommit.

-

Dispersed reloads. The limiting factor for any land battery is the reload. Prepositioned reloads at multiple small sites, plus modular handling gear, shorten the time to put tubes back into action. The more reload points, the harder it is for an adversary to shut down the battery with a single strike.

New angles of fire from the First Island Chain

The First Island Chain is not a monolith. It is a lattice of islands, peninsulas, ports, and airfields that can be used to create overlapping arcs.

-

From northern Luzon, engagement windows open across the Luzon Strait and into the southern approaches to Taiwan. This threatens maritime traffic that supports coercive pressure against the Philippines in the West Philippine Sea and puts a cost on PLA Navy forays east of Taiwan.

-

From Kyushu and western Honshu, arcs can sweep the East China Sea and the Ryukyu island chain approaches, complicating any move to isolate Japanese outlying islands. In concert with Japanese ground-based anti-ship missiles, U.S. Typhon batteries can generate cross-axis dilemmas for ships entering or leaving chokepoints.

-

When linked with air and maritime assets, these land arcs become part of a broader kill box architecture. A target tracked by a Japanese destroyer or a U.S. P-8A can be engaged by the nearest and most survivable shooter, which may well be a concealed launcher on a provincial road.

Plugging Typhon into a U.S.–Japan kill chain

Typhon’s value scales with your ability to find and hold targets. In practice, that means tight alignment with allied sensors and battle networks.

-

Sensing. Maritime patrol aircraft, E-2D airborne early warning, surface radars on Aegis ships, and overhead systems provide wide-area tracks. Japan’s investments in radars and space situational awareness add coverage, especially in the East China Sea. Civil maritime picture feeds can add context in crisis.

-

Fusion. Track-quality data must be correlated, deconflicted, and distributed quickly. The U.S. push toward joint all-domain command and control aims to reduce the time from detection to engagement by connecting sensors and shooters across services. Typhon should be a consumer of that network and, when appropriate, a contributor.

-

Fire control. For moving maritime targets, cooperative engagement concepts let a sensor far from the launcher provide continuous updates. This is where trust and procedures matter. Cross-alliance authorities for retargeting, confirmation of identification, and coordinated fires must be rehearsed before a crisis.

-

Counter-ISR posture. A kill chain is only as strong as its most detectable link. Emission control by sensors, use of passive or low-probability-of-intercept modalities, and deception about where the battery actually is will decide whether Typhon survives long enough to matter.

For how sea-based fires complement land batteries, see hypersonics at sea with CPS.

Signaling, escalation, and alliance politics

Typhon’s appearance in northern Luzon and then in Japan sends clear messages, yet those messages land differently in Manila and Tokyo.

-

Manila’s calculus. The January 2025 decision to keep and relocate the battery inside the Philippines shows the Marcos administration is comfortable with a rotational presence that raises costs on coercion in the West Philippine Sea. It also reflects confidence that dispersed basing and careful procedures can limit escalation. Domestic critics worry about entanglement and retaliation. The choice to train Philippine soldiers on the system’s payload handling indicates Manila wants familiarity and options without immediate ownership. The politics hinge on whether the presence is seen as raising deterrence more than risk.

-

Tokyo’s balance. Japan has embraced a counterstrike posture while remaining sensitive to local basing issues. The public reveal during Resolute Dragon places a U.S. launcher on Japanese soil in a high-visibility setting, while avoiding live fire. That balances deterrent signaling with reassurance that operations will be disciplined, coordinated, and temporary for exercises. Tokyo is likely to frame Typhon as a complementary asset that sits alongside Japan’s growing inventory of indigenous long-range missiles, not as a substitute.

-

Strategic signaling to Beijing. Land-based SM-6 and Tomahawk in the First Island Chain are a message about resilience and depth. They say the United States and allies can impose costs from locations that are hard to roll back quickly and that escalation ladders will have many rungs. Beijing will answer with more ISR, more counterstrike options, and diplomatic pressure on host governments. The central question is whether that exchange stabilizes at a higher deterrence plateau or feeds a perception spiral.

Cost per effect: land launchers versus ships and aircraft

Comparing costs is messy because you are paying for more than a missile. You are paying for access, survivability, and options.

-

Per-shot costs are similar across domains because the missiles are similar. A Tomahawk is a Tomahawk whether it leaves a ship or a truck. An SM-6 brings a premium for multi-mission capability regardless of the launcher.

-

Platform overhead is where land launchers shine. A Typhon battery of a few dozen personnel and trucks can sit forward for months at a fraction of the cost of keeping a destroyer on station. The sustainment bill is lower, and the political cost of rotating a small land unit into an existing base is often easier to manage than the continuous presence of a warship.

-

Magazine depth cuts the other way. A destroyer carries dozens of cells and can reload in secure ports. A land battery’s ready magazine is smaller, and reloads require dispersed stockpiles, specialized handling, and time. In a surge fight, land batteries must plan to mass effects by number of batteries and reload nodes rather than by the depth of a single ship’s magazine.

-

Risk trades differ. Aircraft can surge quickly and reach targets across the theater but risk air defenses and tanker availability. Ships offer mobility and persistence at sea but risk anti-ship missiles and submarines. Land batteries inside allied territory are cheaper to keep in place and harder to find, yet once found, they are vulnerable if they cannot displace between salvos. The smart mix uses all three, with land batteries freeing ships and aircraft to focus on tasks only they can do.

2025 to 2027: doctrine, logistics, and countermeasures

-

Doctrine will move from cameo to cadence. The April 2024 arrival in Luzon was a first look. The January 2025 decision to keep the battery created a steady-state learning lab. The September 2025 reveal in Japan put joint integration on display. Over the next two years expect Typhon to be written into joint maritime denial concepts alongside HIMARS and allied ground-based anti-ship missiles. Expect more rehearsals of cross-service targeting and authorities, especially for dynamic maritime engagements.

-

Logistics become the pacing item. The decisive questions are where reloads sit, how fast they move, and how many handling teams exist per battery. This drives negotiations with host nations about storage, movement permissions, and security at multiple small sites rather than a few big depots. The ability to airlift a launcher, fire, then exfiltrate to a different island or prefecture will separate paper plans from real options.

-

Countermeasures will multiply. The PLA will push more small satellites and long-endurance drones to find batteries, more electronic warfare to strip away targeting links, and more long-range fires to hit reload points. Cyber operations against logistics software and base infrastructure are likely. Expect decoy competitions, tighter emissions control, and deception playbooks to be part of every rotation.

-

Host-nation politics will set ceilings. In the Philippines, continued harassment at sea will likely sustain support for rotational U.S. capabilities, but any incident that harms civilians or is seen as reckless could constrain access. In Japan, careful exercise choreography, transparent safety practices, and visible joint command relationships will be essential to avoid local backlash.

-

Industrial base implications are real. Land batteries that can shoot SM-6 and Tomahawk will compete with ships for the same missile inventory. That argues for higher production rates and for allied co-production or co-financing. The more the alliance leans on land-based shooters, the more it must invest in the mundane gear of reloads, decoys, transporters, and spares.

-

Allied adoption and interoperability. Manila is evaluating what to buy or co-develop for archipelagic defense. Tokyo is fielding longer-range ground-based missiles and may opt to train more deeply with U.S. land launchers even if it does not procure Typhon itself. Australia’s experimentation with land-based maritime strike and joint exercises can create a trilateral playbook for cross-loading sensors and shooters.

What to watch

-

Recurrent rotations. The key indicator is whether Typhon returns to Japan and continues to move among Philippine sites on a predictable training drumbeat. Repetition turns novelty into deterrence.

-

Live-fire events in the First Island Chain. Demonstrations matter for allies and adversaries. A controlled live-fire in an allied range complex would harden joint procedures and signal confidence.

-

Storage and movement agreements. Watch for publicized deals on munitions storage and logistics corridors in the Philippines and Japan. Those are the sinews of a real capability.

-

More decoys and deception. If exercises begin to feature visible decoys and deception vignettes, that is a sign the force is internalizing survivability rather than treating it as an annex.

-

Missile production. Deterrence rests on depth. Rising production rates for SM-6 and Tomahawk, plus allied investments, will tell you whether policy is matched by magazines.

Typhon’s arrival ashore is less about adding a new missile and more about rearranging the geometry of deterrence. By placing multi-mission cells on trucks inside the First Island Chain and wiring them into allied sensors, the United States and its partners are turning geography into a force multiplier. The PLA will adapt. So will Manila and Tokyo. The race now is not only about range or speed, but about who can build and sustain a kill web that is fast, resilient, and hard to unravel.