3I/ATLAS turns the Solar System into a live observatory

In late 2025, interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS crossed the inner Solar System. From Mars orbit to the Jupiter system, a coordinated fleet captured its chemistry, dust, and motion in real time, turning the Solar System into a live observatory.

A rare visitor, caught by a scattered fleet

On October 30, 2025, the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS swept through perihelion, just inside the orbit of Mars. Weeks earlier it had skimmed past the Red Planet, and in November it crossed lines of sight reachable from the Jupiter system. The timing and geometry created a scientific gift: Earth was poorly placed, but a network of spacecraft and telescopes elsewhere could still watch. That network moved quickly.

Within days of discovery in July, observatories around the world and in space began to track the newcomer. The first high-resolution pictures set the tone: a compact, teardrop coma, brightening steadily as sunlight stirred buried ices, with early estimates placing the nucleus at no more than a few kilometers across. NASA centralized key basics about the comet’s path and observing plans for major assets, including Hubble, Webb, SPHEREx, and several Mars and Jupiter missions, which kept researchers aligned on what to watch and when to pivot their instruments toward the visitor. See NASA’s overview of 3I/ATLAS for trajectory, size limits, and campaign planning details in one place, including which spacecraft were tasked and why: NASA’s 3I/ATLAS mission page. For broader context on Webb’s capabilities, see JWST maps off-world climate.

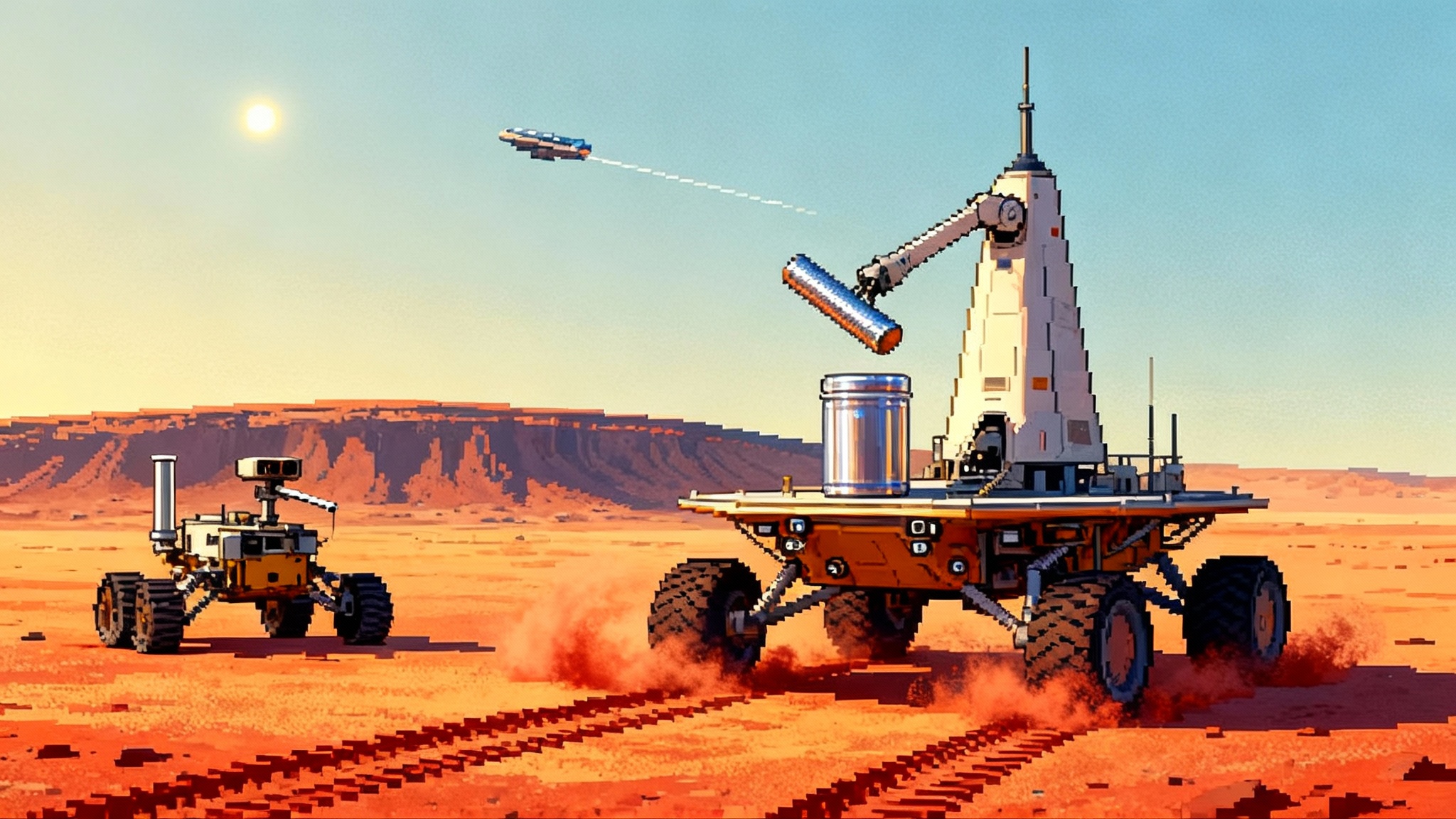

This was not a single telescope story. Europe’s two Mars orbiters tilted their cameras off the planet to chase a faint white dot. The Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, better known as JUICE, prepared to turn its sensors sunward for a difficult, low-data-rate look. Ground-based giants in Hawaii, Chile, and the Canary Islands took turns as the comet rose and set across the globe. The effect was a Solar System-scale observatory, stitched together by shared ephemerides, rapid scheduling, and preplanned playbooks for targets of opportunity.

Why Mars mattered when Earth could not

By early October, from Earth’s point of view, 3I/ATLAS was too close to the Sun for easy observing. Mars was not. On October 3 the comet passed roughly 30 million kilometers from the Red Planet and the European Space Agency seized the chance. The ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter used CaSSIS, a camera built to map Martian surface features, to record a faint moving glow against starfields. Mars Express aimed its own cameras and photometers. Even though neither spacecraft was designed to image such a distant and dim object, both could track the comet’s motion across the Martian sky with precise timing.

That timing mattered. Simultaneous measurements from Mars and from the few Earth-visible windows before and after solar conjunction let navigation teams triangulate the comet’s position and speed with cross-planet parallax. The trick is conceptually simple. If you hold a finger at arm’s length and alternate closing one eye, your finger appears to jump relative to the background. Astronomers did the same with a baseline measured in tens of millions of kilometers. The result is a tighter three-dimensional trajectory, which sharpened predictions for when and where to point every other instrument in the fleet.

An equally important benefit was environmental. Observing from Mars lifted the comet out of the glare and atmospheric scattering that plague solar-adjacent targets from Earth. CaSSIS needed stacks of short exposures, but the Martian vantage removed a layer of noise and allowed a clean measurement of coma size and overall brightness profile without the worst of Earth’s twilight gradients. That, in turn, constrained the rates at which gas and dust were being released.

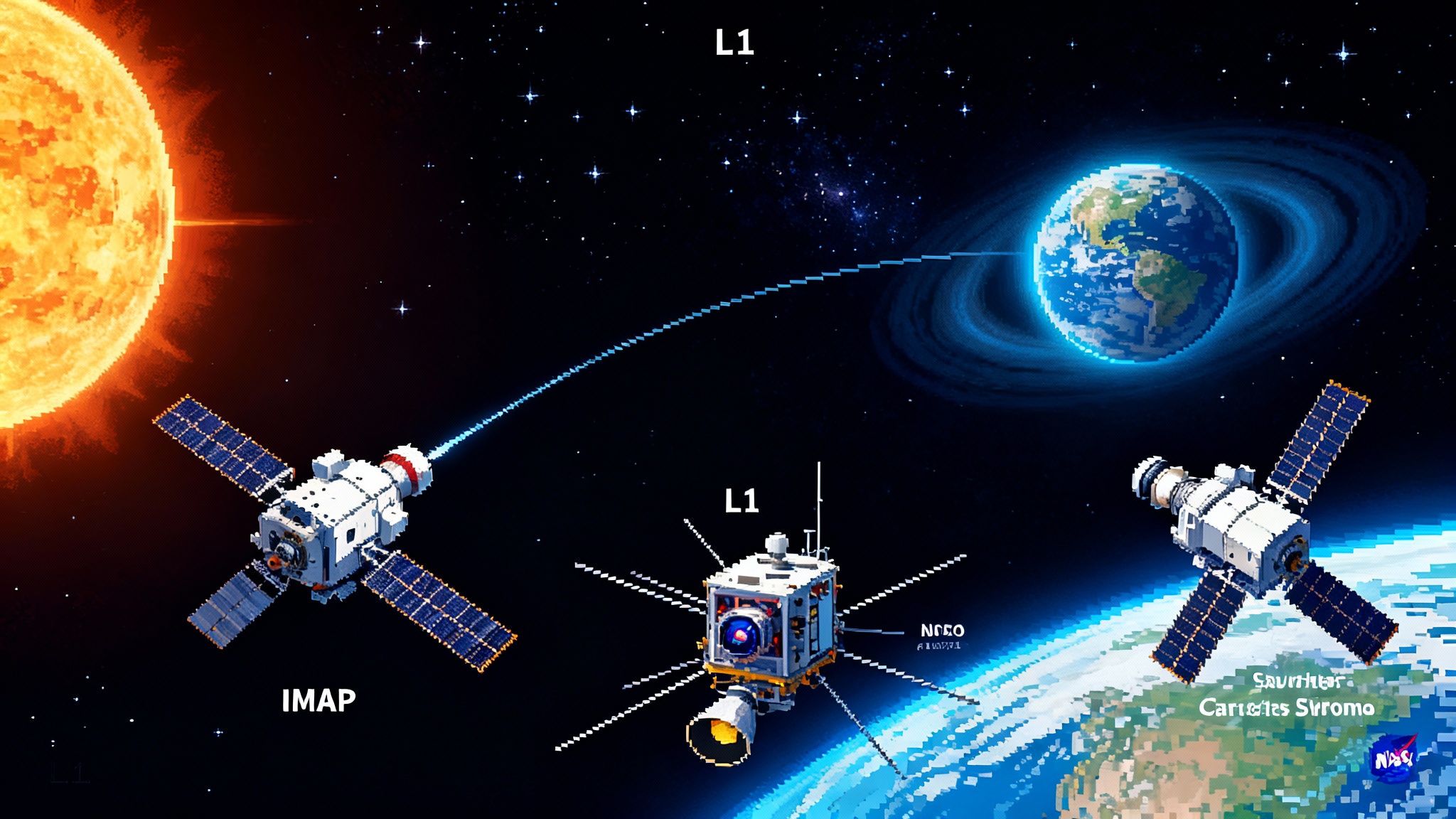

JUICE finds a difficult but valuable angle

In November, ESA’s JUICE attempted observations from well beyond Mars. The spacecraft sat in a tough thermal geometry, using its large high-gain antenna as a heat shield while relying on a smaller antenna for low-bandwidth data. That forced engineers to plan lean observing sequences and accept delayed downlinks. Even so, the vantage had two advantages. First, JUICE looked toward a comet fresh from solar heating, when activity is strongest. Second, the geometry offered a long, slanted line of sight through the tail, enhancing sensitivity to faint dust structures and gas emissions that spread over vast distances. JUICE teams coordinated with NASA’s Europa Clipper on complementary ultraviolet looks, setting up paired datasets that will be cross-calibrated when JUICE’s recordings arrive on Earth in early 2026.

ESA framed this multi-mission window in advance, with a public observing plan for the Mars orbiters in early October and for JUICE through late November. That plan did more than inform the public. It synchronized instrument teams, ground telescopes, and data archives around a shared timeline and cadence, which is essential when a target’s visibility is measured in days. You can see that plan and geometry laid out in ESA’s campaign note: ESA’s Mars and Jupiter missions observe 3I/ATLAS.

Early science in three threads: chemistry, dust, and dynamics

-

Chemistry. Early spectroscopy in late summer delivered the big headline: strong carbon dioxide emission with clear water ice signatures. That combination is consistent with a chemically rich, cold-formed comet that has spent eons in deep space before this solar flyby. Infrared surveys mapped an extended carbon dioxide coma hundreds of thousands of kilometers wide, implying vigorous outgassing. Water vapor limits and evolving bands point to layered ices that respond differently to sunlight as the nucleus rotates. In practical terms, this is a lab test of planetary formation models that predict how volatile ices freeze and segregate in protoplanetary disks around other stars.

-

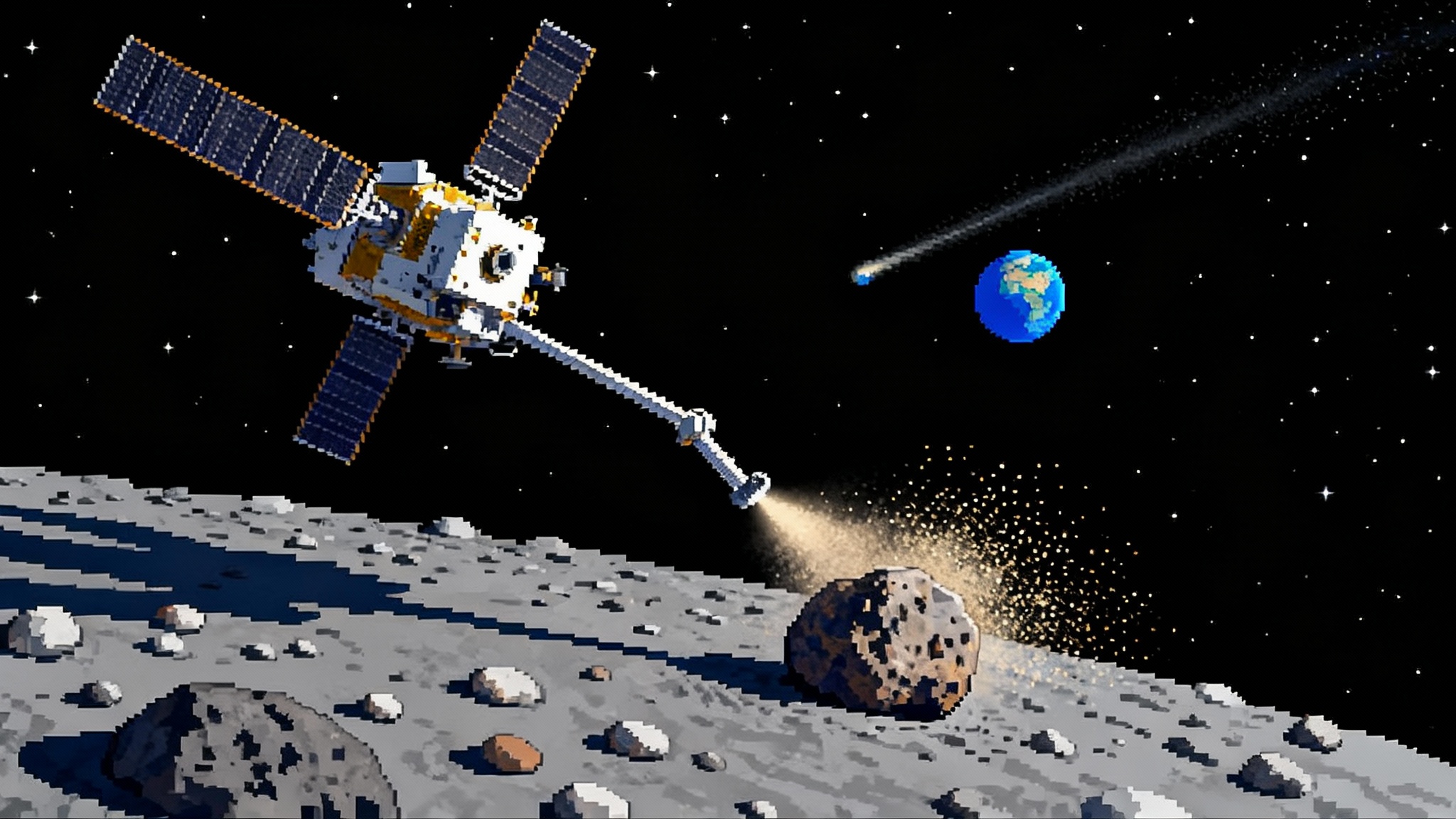

Dust. From July through October, images showed a compact, teardrop-shaped coma and a tail that lengthened as perihelion approached. The tail’s structure evolved from a short wedge to a longer, more filamented streamer, a sign that larger grains lagged behind smaller ones accelerated by solar radiation. Polarimetry by several ground telescopes hints at dust grains with sizes and coatings unlike many short-period comets from our own Kuiper Belt, a difference that may trace a different birth environment. Taken together, the dust color, polarization, and brightness profile suggest grains that are less processed by repeated solar heating.

-

Dynamics. The refined trajectory shows a clean hyperbola, as expected for an unbound interstellar object. Small non-gravitational kicks from outgassing are present but modest, and they tracked changes in brightness as activity waxed and waned. Parallax between Mars and Earth anchored the ephemerides enough to schedule narrow-slit spectrometers and narrow-field imagers across observatories that normally would be hesitant to commit precious time on a moving, uncertain target. This is exactly the sort of practical win that cross-planet baselines were expected to deliver.

To put the scale in context, Hubble observations place a firm upper limit on the nucleus diameter near 5.6 kilometers, with some solutions allowing a much smaller body masked by a bright, dust-rich coma. That spread is not unusual in early comet work, because the sunlit envelope is orders of magnitude larger and brighter than the solid core beneath it.

The campaign playbook that made it work

Observers did not improvise from scratch. They pulled a playbook from two decades of comet campaigns and updated it for an interstellar target that would be visible for only a few months in 2025.

-

Cross-planet parallax, operationalized. The geometry was recognized early, and teams allocated synchronized windows. Parallax is not merely a pretty geometry trick. It feeds the orbit solvers that determine where to place a spectrograph slit a week later, which determines whether someone captures a clean line for carbon monoxide or misses by a few arcseconds. Downstream, it reduces wasted time and improves the odds that multiple facilities record the same feature under similar viewing angles.

-

Rapid scheduling at scale. Queue-scheduled telescopes like Gemini South, the Very Large Telescope, and Keck slotted in short monitoring runs that rode between longer programs. Small robotic networks contributed cadence and weather resilience. On the spacecraft side, engineers prepared “slew and stare” templates so that teams could validate a new pointing and exposure plan in hours, not weeks. When the comet grew brighter than expected in late September, those templates enabled a higher frame rate and better tracking without rewriting the entire pipeline.

-

Data fusion with purpose. Teams shared not just images, but calibrated brightness profiles, time-tagged slit positions, and dust color indices. Those products feed multiphysics models that connect gas production, dust drag, and sunlight pressure to visible morphology and spectral lines. The goal was not simply to assemble a pretty collage. It was to derive the fluxes of carbon dioxide and water, the dust-to-gas ratio, and the grain size distribution that best match observations from three vantage points. That is how you turn a sky show into constraints on how other planetary systems build comets.

-

Acknowledging the limits and using them. Mars orbiters were not designed to do deep comet spectroscopy. JUICE had to ration downlink and protect itself from the Sun. Ground-based assets lost weeks to solar glare. Rather than fight the constraints, the campaign treated each capability as a piece of coverage, like a relay team where each runner has a different stride. The result was continuous context rather than isolated snapshots.

The surprises that opportunity delivered

Three unplanned dividends stood out.

-

A clean tail-through-the-plane view. From Mars, observers caught the comet with a viewing angle that maximized the column of dust and gas along the line of sight. That geometry accentuated faint structures that would be hard to see from Earth and will inform how we interpret tail shapes in other comets when geometry is less favorable.

-

A better handle on activity onset. With Earth mostly blinded by solar proximity in October, Mars and JUICE covered the rise and immediate decline around perihelion. That continuous arc captured the moment when sunlight began releasing carbon dioxide more rapidly than water, a clue to ice layering and to the thermal properties of surface crusts that insulate deeper ices.

-

A rehearsal for coordinated ultraviolet work. The potential pairing of JUICE ultraviolet observations with Europa Clipper’s ultraviolet spectrograph created a template for cross-mission spectral comparisons. Even with delayed downlinks from JUICE, synchronized timing means that, months later, teams can line up spectra taken near the same minute and compare features across instruments. That gives the field a clean test of instrumental cross-calibration that will pay off far beyond this comet.

From reactive to ready: a quick-reaction architecture for the next 4I

3I/ATLAS demonstrated that the Solar System already functions as a distributed observatory when the community acts in concert. Detection and early warning are improving with missions like NEO Surveyor integration in 2025. But this campaign also exposed friction that cost hours and days in a clock-driven event. If we want the next interstellar visitor to yield more than good pictures, we need a standing, quick-reaction architecture. Here is a concrete version of that idea.

-

Preplanned spacecraft tasks. Every deep-space mission should carry a small library of target-of-opportunity scripts: slew rates, exposure ladders, tracking modes, telemetry budgets, and thermal constraints, pre-vetted and stored onboard. The operational idea is simple. When the Minor Planet Center posts a likely interstellar orbit, operations can push a file that turns a planetary mapper into a comet tracker within one planning cycle. For Mars orbiters, that means CaSSIS-like stacks, horizon-safe pointings, and onboard star-tracker assists to hold a moving target. For outer planet craft, it means ultraviolet and infrared integrations tuned for low surface brightness at long range.

-

Smallsat interceptors on standby. A handful of 50 to 200 kilogram spacecraft parked at gravitational waypoints could sprint on short notice. They would not need to be fast by flagship standards; a modest chemical stage and solar electric thrusters can deliver a quick flyby if the alert comes early. The payloads are simple and proven: a narrow camera for nucleus shape and spin; a medium-field dust imager; a compact ultraviolet spectrograph for carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen lines; and a mass spectrometer if we can afford it. For a relevant precedent, see Tianwen-2 comet encounter plans.

-

Automated pipelines from alert to archive. The first hours after an alert are often lost to plumbing. We can fix that with a standardized pipeline that ingests preliminary orbits, produces pointing tables for common instruments, and posts machine-readable schedules. A companion data pipeline would tag and time-align observations by geometry rather than just by mission and instrument, so that a radiative-transfer modeler can pull every spectrum taken at a given phase angle, no matter the facility. This is a solved problem in other domains. Weather satellites and radar networks already auto-fuse multi-sensor data on tight deadlines. We should do the same for interstellar targets.

-

A governance lightweight enough to work fast. No one needs a new agency. What the field needs is a persistent, opt-in coordination layer with a published playbook. Assign a small rotating secretariat drawn from existing planetary defense offices and national observatories. They do not grant time or control spacecraft. They keep a shared calendar, run drills twice a year, and ensure that when the alert hits, the right people have each other’s phone numbers and a common file of template requests ready to send to their time allocation committees and mission operations.

Concrete actions before the next alert

-

Put the scripts onboard. Mission teams can add a handful of pointing and exposure templates within their current software update cycles. Write them, test them against star-catalog simulations, and include them in the next maintenance upload.

-

Publish the playbook. The community should settle on a short, stable document that lays out the first 72 hours after an interstellar candidate is flagged: who computes refined orbits, who translates them into pointings for major facilities, how conflicts are resolved, and how updates are broadcast.

-

Fund two interceptor buses to flight-qualify in parallel. The first unit proves the spacecraft and the ground segment. The second learns from the first. Keep the payload common across both. If no interstellar target appears in time, divert one to a long-period comet from the Oort Cloud and treat it as a rehearsal.

-

Stand up the geometry-first data catalog. Seed it with 3I/ATLAS products. Organize by observing geometry and viewing wavelength, not by mission. Invite modelers and instrument teams to plug in their tools. Reward speed and correct metadata as much as signal-to-noise.

-

Rehearse with real comets. Choose one inbound long-period comet per year as a drill. Run the full play: parallax, rapid scheduling, data fusion, and public releases that explain not just what we saw but how we coordinated.

The bigger payoff

Why does all of this matter? Because interstellar comets let us examine the leftovers of other planetary systems without leaving home. Chemistry tells us what ices and organics are common out there. Dust reveals how grains were processed in their birth disks. Dynamics encodes the gravitational shoves that kicked these objects loose. 3I/ATLAS showed that a loosely coupled fleet can extract that information in real time when the geometry is right.

The lesson is practical and optimistic. We do not need to wait for a single perfect mission to answer every question. We can turn the Solar System itself into an agile observatory, one that spans planets and spacecraft and national programs, if we make a few smart investments in readiness. The next visitor will not wait for us. With the right playbook, we will be ready when it appears, and we will not just watch it pass. We will capture it scientifically, together.