Alzheimer’s enters the bloodstream: pTau217 tests arrive

From the May 16, 2025 FDA clearance to an August nationwide rollout, a plasma pTau217 blood test is reshaping how we detect Alzheimer’s pathology. See who should be tested, how to interpret results, and what this means for care, prevention, and access.

The moment the blood test arrived

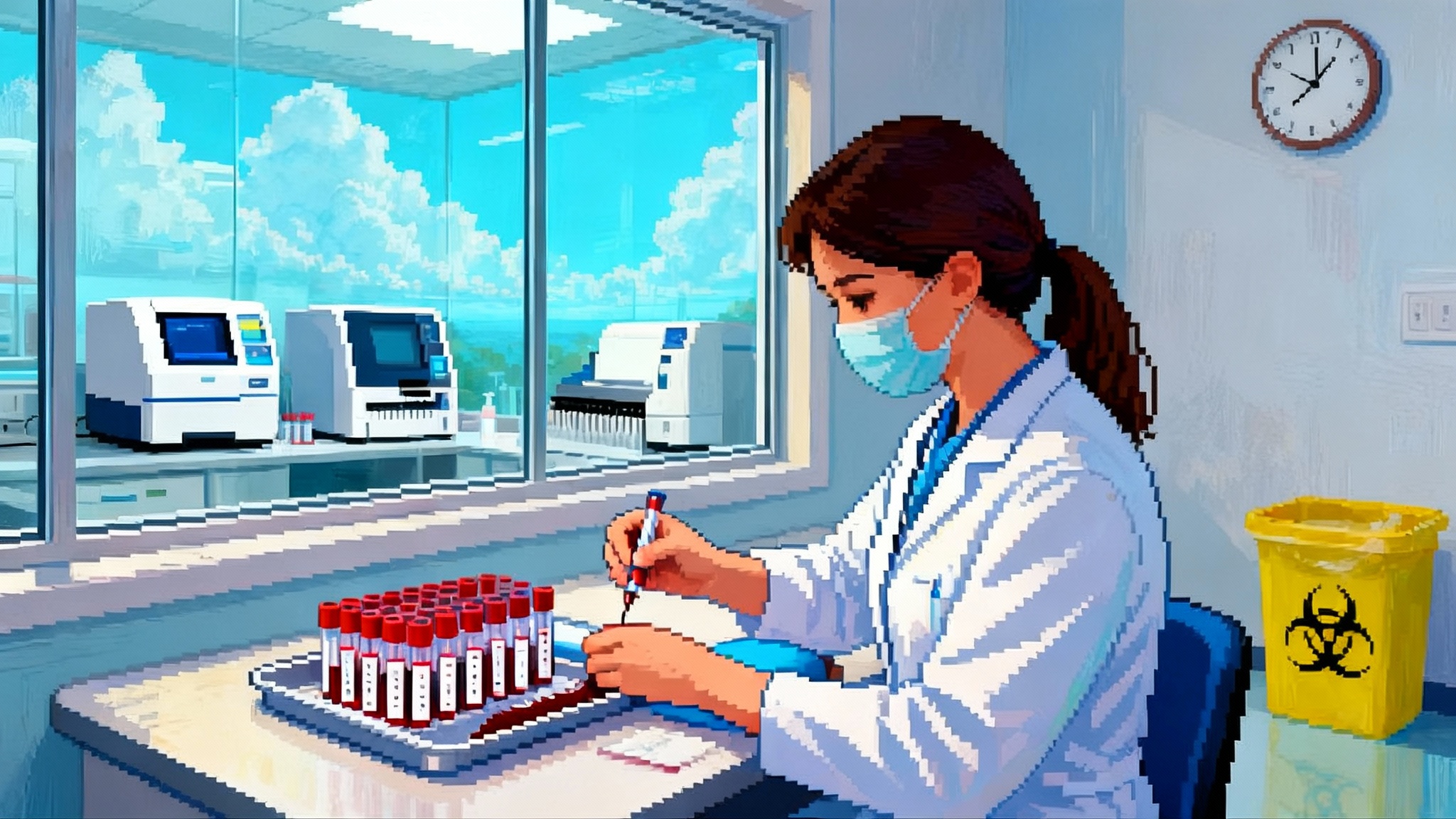

On May 16, 2025 the United States crossed a threshold in brain health. The Food and Drug Administration cleared the first blood test to help identify Alzheimer’s pathology in living patients, a lab assay that measures the ratio of pTau217 to beta amyloid 1-42 in plasma. The agency’s decision established a new clinical route to detect amyloid plaques without a spinal tap or a PET scan, and it did so for a defined population: adults 55 and older who already show signs or symptoms of cognitive decline. In plain terms, the playbook for how we diagnose and manage memory disorders changed in a day. You can read the announcement in the agency’s language, but the upshot was simple and profound: a blood draw could now stand in for much of the heavy lifting formerly done by imaging and cerebrospinal fluid analysis, especially to rule out Alzheimer’s pathology. FDA cleared the first blood test.

What followed was just as important. By mid August, large national laboratories had turned regulatory clearance into clinical reality. Labcorp announced that the same pTau217 to Aβ42 plasma ratio assay would be available nationwide through its network, bringing the test into community phlebotomy sites and primary care workflows across the country. That means patients no longer have to live near a tertiary memory clinic to access modern biomarkers. The path from an FDA green light in May to a practical blood draw in August was short, and it reframed how quickly Alzheimer’s diagnostics can reach people where they receive most of their care. See rollout details in Labcorp’s announcement: available nationwide through Labcorp.

What this test actually measures

The plasma assay quantifies two proteins that move in opposite directions as Alzheimer’s pathology builds. Phosphorylated tau at the 217 site tracks with tau pathology and the downstream effects of amyloid. Beta amyloid 1-42 tends to decline in biological fluids as it is deposited into plaques. The ratio of pTau217 to Aβ42 correlates with the presence or absence of amyloid plaques on PET or with approved cerebrospinal fluid panels.

In FDA-reviewed data, the blood test correctly aligned with amyloid PET or CSF in the vast majority of symptomatic patients, with high negative agreement that makes it well suited as a triage tool to rule out Alzheimer’s pathology in the right clinical context. A nontrivial minority will receive an indeterminate result that defers back to imaging or CSF. And because the test detects biology rather than cognition, clinical judgment anchors interpretation. A positive biomarker is not a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia.

Why May to August matters for brain aging

Speed to access is not a trivial footnote in neurodegeneration. Long waits for PET scans and specialist visits erode the window in which disease-modifying therapies can help. A community blood draw can cut months from that wait. Earlier confirmation or exclusion of Alzheimer’s pathology allows clinicians to channel patients into the right lane sooner: medication for amyloid positive, symptom management and a different diagnostic workup if negative, and risk reduction for all.

Cost matters too. PET scans and lumbar punctures are effective but expensive or invasive. A blood test that can reliably spare many patients from confirmatory imaging reduces barriers for people far from specialty centers and for those uneasy with a spinal tap. That is the path to broader equity in diagnosis, provided we roll the test out responsibly.

Who should be tested

- Adults 55 and older with a documented cognitive complaint and objective evidence of impairment on a validated screen or neuropsychological testing.

- People already being evaluated for possible Alzheimer’s disease by a primary care clinician or specialist, where the result will change management.

- Individuals being considered for anti amyloid therapy who need evidence of amyloid pathology to proceed.

- Candidates for research studies or clinical trials that require biomarker confirmation.

Who should not be tested

- Asymptomatic people seeking a screening test for peace of mind. This assay is not a screening tool, and testing without a clinical concern can cause harm.

- Individuals younger than 55 or those with clear non Alzheimer’s explanations for symptoms, such as medication effects, untreated major depression, delirium, normal pressure hydrocephalus, or thyroid and B12 abnormalities.

- People for whom the result will not change care. If advanced dementia is already present and goals of care exclude disease modifying therapy or further diagnostics, skip biomarker testing.

- Anyone unwilling to act on either result. If a positive would not lead to referral or therapy consideration, and a negative would not prompt a search for other causes, testing may not be appropriate.

Accuracy and limits versus PET and CSF

Think of the plasma pTau217 to Aβ42 test as a sophisticated filter. In symptomatic patients, a negative result carries a high probability that amyloid plaques are not the driver of the cognitive problem at that time. That reduces the need for PET and spares many patients a lumbar puncture.

A positive result is different. It greatly increases the probability of amyloid pathology but does not stand alone as a diagnosis. Confirmatory testing or specialist evaluation remains prudent, especially before launching therapies with significant monitoring needs. Indeterminate results point to the same path. And there are caveats: comorbid neurodegenerative diseases, vascular injury, chronic kidney disease, and assay variability at extremes of age can influence levels. Clinicians should interpret results against the patient sitting in front of them, not against a threshold in isolation.

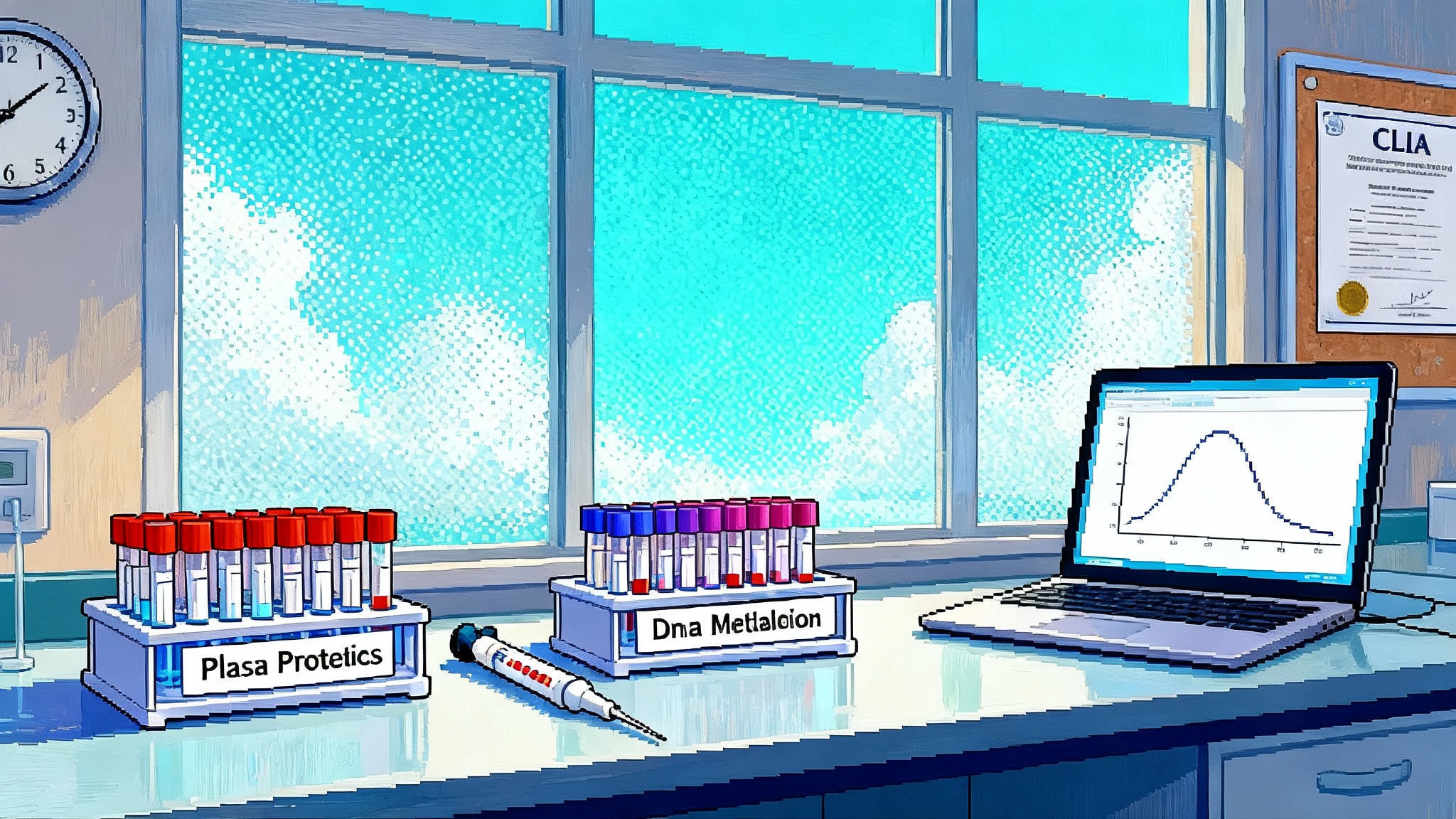

Professional guidance is starting to catch up. In July 2025 the Alzheimer’s Association issued its first clinical practice guideline on blood based biomarkers, recommending that in specialty care these tests can triage symptomatic patients by ruling out Alzheimer’s when sensitivity is very high, and that positive results should be confirmed unless accuracy meets stringent thresholds. That is the middle road between access and caution.

What the result changes in care

- Negative result: Focus on alternative diagnoses and treat reversible contributors. Depression, sleep apnea, medication burden, autoimmune or infectious processes, cerebrovascular disease, and frontotemporal degeneration move to the top of the list. Reassure the patient that Alzheimer’s pathology is unlikely to explain current symptoms, continue follow up, and lean into risk reduction.

- Positive result: Refer to a memory specialist if not already involved. Discuss anti amyloid therapies and monitoring needs. In shared decision making, weigh benefits and risks, the patient’s values, caregiver capacity, MRI access, and coexisting conditions. Many centers will still confirm with CSF or PET before starting therapy, but a plasma positive can get the process moving faster.

- Indeterminate result: Explain the uncertainty and arrange the next step, typically CSF biomarkers or amyloid PET, along with continued clinical assessment.

Implications for anti amyloid therapies

Both of the FDA approved anti amyloid monoclonal antibodies for early symptomatic disease require evidence of amyloid pathology before treatment and careful MRI monitoring during treatment. A widely available blood test changes logistics. Instead of waiting weeks for imaging, a clinician can obtain a plasma result at the outset of evaluation. If negative, you likely spared the patient from procedures they did not need. If positive, you have a clear signal to proceed with confirmation and therapy counseling sooner. Faster triage means more patients can start therapy while still in the mild stage, where benefit is modest but meaningful.

This also helps with therapy safety. These drugs can cause amyloid related imaging abnormalities that require MRI monitoring and careful dose decisions. A blood based triage step reduces unnecessary MRI exposure by steering amyloid negative patients away from therapies they would not benefit from. For a broader view of brain aging therapeutics, see how an autophagy drug targets brain aging.

Clinical trials and the enrollment bottleneck

Trials for new Alzheimer’s drugs and prevention strategies are often slowed by screen failures when patients who clinically appear to have Alzheimer’s turn out to be amyloid negative on PET. A plasma pTau217 assay allows researchers to pre screen more efficiently, reduce the number of fruitless PET scans, and shorten the time from first contact to randomization. That lowers trial costs, which helps sponsors take more shots on goal, including trials that test risk reduction in midlife and combinations of therapies.

Equity and access

PET access is uneven in the United States and lumbar punctures are not universally available in routine care. A blood draw at a neighborhood patient service center is different. It meets people where they live. That said, equity is more than geography. Validation across diverse populations matters, because biomarker distributions and comorbidities can differ by ancestry, socioeconomic status, and exposure history. Health systems should track performance by race and ethnicity, ensure interpreter services during counseling, and offer low cost follow up imaging when needed. We also need to watch for new inequities: if one plan covers plasma biomarkers and another does not, access will again split along income and employment lines. For the policy backdrop shaping diagnostics, see how the FDA LDT rollback reshapes biomarkers.

Primary care, Monday morning

Here is a practical way to fold the new test into everyday practice.

-

Identify the right patient. Age 55 or older with a credible cognitive complaint corroborated by a family member or friend.

-

Screen and stage. Use a validated instrument such as MoCA or MMSE, and obtain a functional history to judge whether the patient is in subjective decline, mild cognitive impairment, or mild dementia.

-

Rule out the reversible. Order a basic lab panel that includes CBC, CMP, TSH, B12, and screen for depression and sleep apnea risk. Consider MRI for vascular changes, normal pressure hydrocephalus, or other structural causes when indicated.

-

Counsel before the blood draw. Explain what the pTau217 to Aβ42 test measures, that it is not a diagnosis on its own, and how the result will shape next steps. Document informed consent.

-

Order the plasma test. Use a national lab with clear reporting and turnaround times. Prepare the patient for the small chance of an indeterminate result.

-

Interpret in context. Negative likely rules out Alzheimer’s pathology at this time. Positive increases the likelihood but usually needs confirmation before disease modifying therapy. Indeterminate calls for PET or CSF.

-

Plan the path. For positives, refer to a memory specialist, review therapy options and MRI monitoring, and check blood pressure, anticoagulation, and APOE status if local protocols require it. For negatives, intensify workup for other causes and focus on risk reduction.

-

Close the loop. Schedule follow up, share results with the patient and care partner in accessible language, and avoid medical jargon.

Payer coverage and practical costs

Expect the coverage landscape to evolve through late 2025. FDA clearance usually improves the chance that Medicare and commercial plans will cover a diagnostic test when used for a medically necessary indication in a defined population. Early in a national rollout, however, plans often require prior authorization or limit coverage to certain settings. Pricing varies by lab and region, and out of pocket costs depend on plan design and deductibles. When counseling patients, emphasize that a negative plasma test can avert the far higher costs and burdens of PET and lumbar puncture, and that coverage is more likely in symptomatic adults 55 and older when the result will change management. Encourage patients to ask their plan about medical necessity criteria and expected member cost sharing before proceeding.

Pair biomarker testing with midlife risk reduction

A blood test does not change what we already know about cognitive aging. The biggest wins for population brain health still come from risk factor control in midlife and early late life. Use the conversation around biomarker testing to double down on the levers that delay decline.

- Blood pressure. Keep systolic blood pressure under good control, especially from ages 40 to 75. Treat hypertension with lifestyle and medication as needed.

- Hearing. Address hearing loss with a proper audiology assessment and hearing aids. Untreated hearing loss is among the most important modifiable risks for later cognitive decline.

- Sleep. Screen for sleep apnea in snorers and in those with daytime sleepiness, resistant hypertension, or atrial fibrillation. Treat insomnia with cognitive behavioral therapy when possible rather than long term sedatives.

- Metabolic health. Prevent or reverse insulin resistance with weight management, physical activity, and glucose control. Diabetes care that emphasizes time in range likely supports brain health over decades. For a systems level view of obesity pharmacotherapy, explore GLP-1s at population scale.

- Vascular and inflammatory drivers. Do not smoke. Treat atrial fibrillation and hyperlipidemia. Move daily with at least 150 minutes per week of moderate activity. Maintain oral health and vaccinations to reduce inflammatory load.

- Mental and social engagement. Foster purpose, social connection, and cognitive challenges that matter to the individual. Isolation accelerates decline; engagement slows it.

These actions apply whether the plasma test is negative or positive. If anything, a positive biomarker result is a fresh reason to optimize blood pressure, hearing, sleep, and metabolic health with urgency.

What comes next

Expect more than one blood based assay to land in clinical workflows. Assays will diversify beyond pTau217, and comparative studies will sharpen thresholds, show where accuracy truly matches PET and CSF, and define when blood tests can substitute entirely for more invasive diagnostics. Health systems will build reflex pathways that combine clinical staging with plasma biomarkers, and payers will refine coverage as evidence matures. Most crucially, primary care teams will become the front door for biomarker informed brain health, triaging who needs specialty care now and who needs risk reduction first.

The May to August shift in 2025 was not just regulatory news. It was a practical reset. When a blood draw can guide the first big decision in a memory evaluation, earlier, cheaper, and more equitable diagnosis stops being a talking point and starts being standard practice. If we pair that access with smart workflows and relentless attention to midlife prevention, we can bend the arc of brain aging toward a longer healthspan, not just a longer life.