Japan’s Tomahawk Era Begins as Destroyers Join U.S. Kill Web

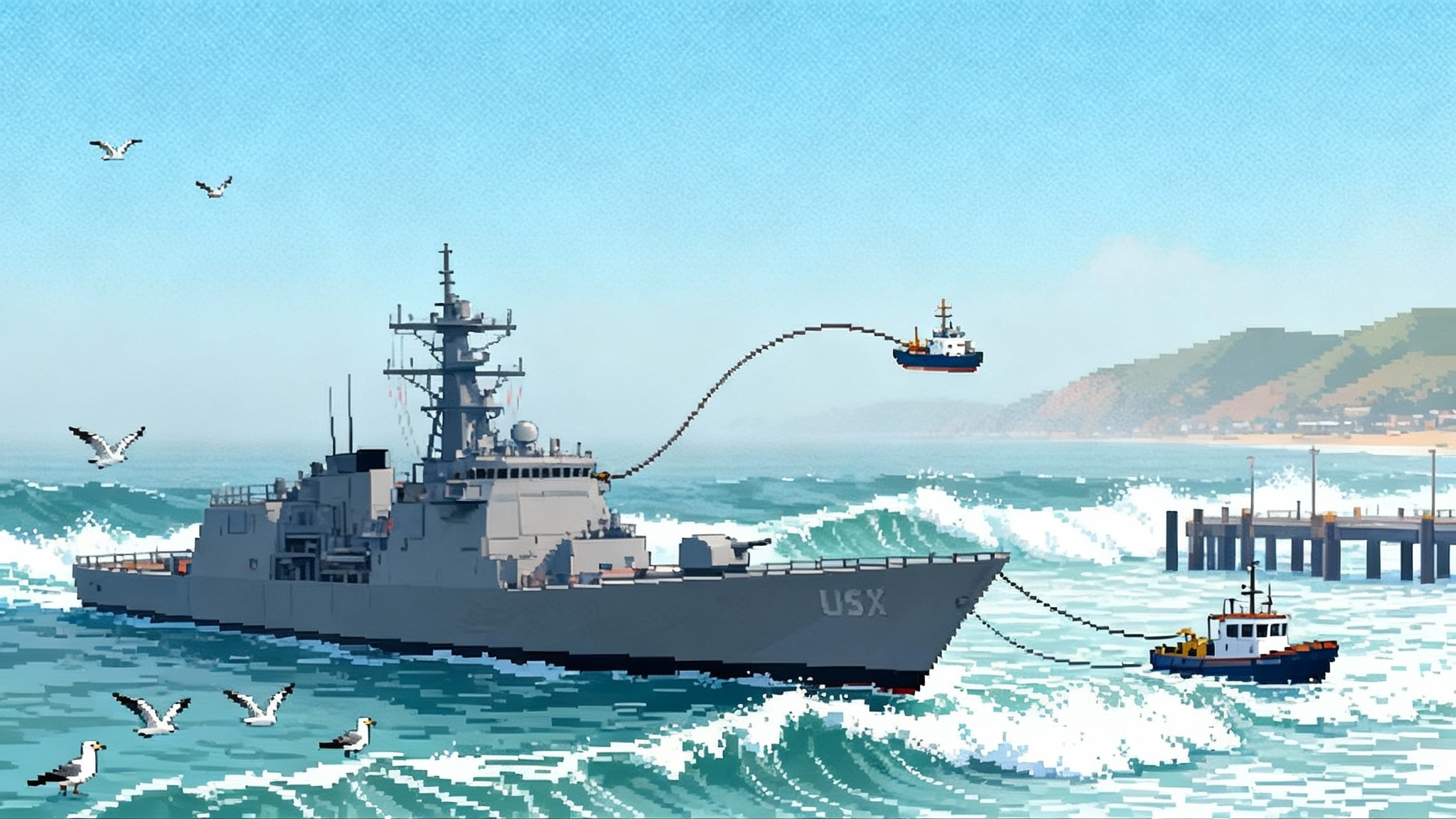

Tokyo is fitting Tomahawk Block IV and V on Kongo and Atago Aegis destroyers, launching a 2025 to 2027 rollout that ties Japanese shooters to U.S. sensors and command networks and reshapes Indo-Pacific strike math.

Breaking the fifty-year pattern

For half a century the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force fought with one arm tied behind its back. Its Aegis destroyers could see far and swat down incoming missiles, but they could not hit deep. That changes now. Japan has started integration work with the United States to bring Tomahawk cruise missiles onto frontline destroyers, with initial deliveries beginning in the 2025 fiscal year and fleet rollout scheduled through 2027. Tokyo signed for 400 missiles in 2024, a split of 200 Block IV and 200 Block V, along with the fire control gear and training package that turns Aegis ships into long-range strike shooters Japan signs deal for 400 Tomahawks.

Think of the Indo-Pacific like a chessboard where one side had only knights and bishops. That side just got queens. Tomahawk at sea gives Japan the ability to reach fixed targets far inland and moving ships far beyond the first island chain. The effect is not only about range. It is about how Tomahawks plug Japanese destroyers into a larger Allied kill web where any credible sensor can cue any capable shooter in minutes.

What ships get the missiles first

Japan will field Tomahawks across its Aegis-equipped destroyers, with near-term focus on the Kongo and Atago classes that already have the right launchers and combat systems to accept the weapon with software and hardware upgrades. The Kongo class carries roughly 90 vertical launch cells and the Atago class about 96, enough to mix air defense interceptors like Standard Missile 2 or Standard Missile 6 with a magazine of Tomahawks that can be surged for a crisis. The newer Maya class will follow as its command and sensor upgrades mature.

The rollout window matters. Japan compressed the schedule by shifting half of the buy to Block IV rounds that are easier to supply quickly, while still locking in the newer Block V line. Block IV brings proven land attack and loitering features. Block V adds a hardened navigation and communications package and creates two paths. Block Va, often called Maritime Strike Tomahawk, adds a seeker to chase moving ships at sea. Block Vb swaps in a multi-effects warhead to break hardened targets. Together they let commanders pick the right arrow for each target set.

Expect the first operational Japanese destroyer with Tomahawk to stand ready in the latter half of 2026, with additional hulls following through 2027 as yards complete combat system updates, crews certify, and magazines fill. Japan is sequencing installation work to avoid pulling too many air defense ships offline at once, especially in the southwest approaches where scramble rates remain high.

The new kill web in plain language

Americans often describe their emerging targeting architecture as a kill web. The term sounds abstract, so here is a simple way to picture it. Imagine a fishing fleet scattered across a wide ocean. Some boats have nets, others sonar, others radios, and a few carry the harpoons. In older practice, the harpoon boat had to find its own fish. In a kill web, any boat that finds fish can whisper its location to any boat with a harpoon, instantly.

Japan has been quietly building the radios, the sonar, and some harpoons of its own. The destroyers bring Aegis combat systems with Cooperative Engagement Capability on newer hulls. The Air Self-Defense Force flies E-2D Advanced Hawkeye aircraft that act like aerial radar pickets and data routers. Joint and combined command centers stitch these feeds together through Link 16 and national networks. Into this mesh come United States sensors that Japan can access in combined operations. Think of U.S. P-8A maritime patrol planes tracing ship wakes, MQ-4C high-altitude drones sweeping thousands of miles of ocean, and national satellites tying motion to coordinates, including proliferated low orbit layers such as SDA Tranche 1 and HBTSS. The destroyers become the harpoon boats, able to receive a firing solution from far away and launch a Tomahawk without revealing their own radars or turning on every sensor at once.

The United States Navy has already started teaching Japanese crews how Tomahawk tasking, safety, and strike workflow actually feel in a combat information center. The first round of JMSDF training took place on a forward-based American destroyer at Yokosuka, with Japanese watch teams practicing the end-to-end sequence from mission receipt to simulated launch U.S. Navy Tomahawk training for Japan.

This matters because the slowest part of a long-range strike is not the missile in flight. It is the human network that must validate the target, deconflict airspace, manage escalation, and ensure the shot is legal and wise. Shared procedures reduce that friction. The closer Japan’s process aligns with the United States process, the faster the web moves when it counts.

Why this flips strike math in the Indo-Pacific

Until now, long-range conventional strike in the region depended on a small number of Allied aircraft that had to fly close to defended airspace, or on submarines whose location and magazine size are tightly limited. Tomahawk on surface combatants changes the denominator. A task group of four destroyers can quietly bring 40 to 80 land attack rounds while still keeping most cells for air defense. Multiply that by several groups and you get persistent, distributed pressure that an adversary cannot predict.

There is also the geography. Tomahawks let Japanese ships hold at risk coastal air bases, missile brigades, logistics depots, and command nodes without crossing the Taiwan Strait or the Luzon Strait. They can impose dilemmas at the start of a crisis by forcing an opponent to defend many points at once, some hundreds of miles inland. That dilutes the effectiveness of anti-ship ballistic missiles by expanding the set of places the opponent must protect, not just the sea lanes.

Finally, a mixed Block IV and Block V inventory complicates defenses. Some missiles can loiter and be retargeted midcourse as new information arrives. Others can dive on moving ships at sea as part of a coordinated salvo with aircraft-launched anti-ship missiles. Add American shooters to the mix and you get combined salvos that arrive from different axes and altitudes, overwhelming point defenses that were optimized for one threat at a time.

Targeting and deconfliction without the jargon

Long-range strike is less like pulling a trigger and more like coordinating a relay race. The baton is a track of target coordinates that must be cleaned and confirmed at each handoff. A radar sees a shape. An electronic sensor hears a radar mode. A satellite watches a convoy move. Someone fuses this into a target card. Someone else confirms that the convoy is not a decoy or a civilian column. A legal advisor checks rules of engagement. The strike cell assigns the shot. The launching ship receives a mission data package. Only then does a missile leave the rail.

Japan’s advantage is that it can now participate in this sequence not just as a sensor but as a shooter. That unlocks reciprocity. If a Japanese E-2D detects a high-value ship and conditions are right, an American destroyer can shoot. If a U.S. P-8A pins down a mobile launcher, a Japanese destroyer can shoot. The web finds the most survivable launcher in the best position and uses it, which keeps costs down and reduces risk to the most fragile platforms.

The hard truth about reloads

Missiles are not infinite. A destroyer’s vertical launch system is a metal magazine. Once you shoot, those cells are empty until you reload in port or alongside a heavy-duty pier crane. At-sea reload exists in concept and has been tested, but it is not a routine fleet skill. That reality will shape Japanese plans.

In a crisis, commanders will likely stage destroyers in pulses. A forward pulse carries a modest Tomahawk load while preserving air defense density. A rear pulse holds more Tomahawks and guards the approaches against submarines and long-range bombers. When the forward pulse expends weapons, it falls back to reload while the rear pulse surges forward. That sounds simple, but it depends on industrial basics. Do you have the pier cranes, the certified crews, the safety zones, and the trained ordnance teams to swap dozens of canisters quickly and safely, day or night, under pressure.

Japan is preparing the unglamorous pieces. Magazine safety rules are being updated. Pier infrastructure is being sequenced to match the upgrade schedule of each destroyer. The defense ministry is aligning stocks of canisters, test sets, and spares with the training calendar so ships do not sit idle waiting for parts. None of this makes headlines. All of it determines whether a Tomahawk force remains a one-shot novelty or a sustainable capability.

How China will counter

- More and better maritime targeting. China will push wider constellations of small satellites, more persistent unmanned aircraft over open ocean, and more distant over-the-horizon radars. The goal is not pinpoint accuracy all the time. It is to keep a running picture of where Allied surface groups might be and to cue shadowing aircraft and ships.

- Heavier anti-ship pressure at longer ranges. The People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force already fields anti-ship ballistic missiles like DF 21D and DF 26. Expect higher inventories and faster firing drills that try to saturate air defenses and force Allied ships to maneuver rather than shoot. Coastal aviation regiments will press hypersonic anti-ship missiles and very low altitude cruise missiles to complicate defenses.

- Base hardening and decoy deception. Tomahawks stress air bases and missile brigades within reach. Expect rapid construction of shelters, fake revetments, decoy emitters, and mobile command posts. Expect more frequent unit dispersal to civilian fields and road bases, especially during exercises that could mask a crisis move.

These moves do not erase the new Japanese capability. They change the price of using it. The answer is to spread risk and multiply magazines.

What this unlocks next

-

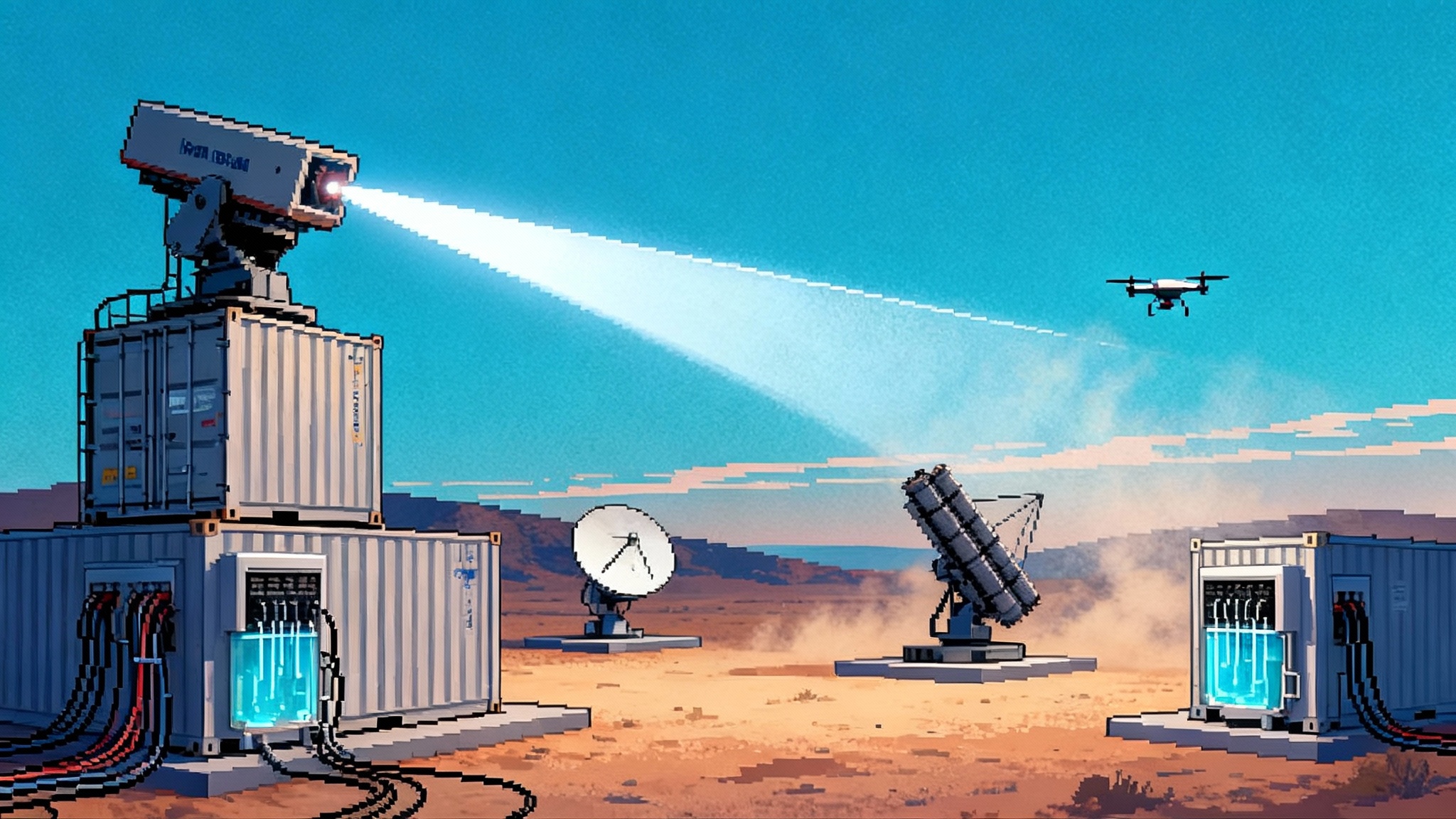

Distributed magazines at scale. Japan can place more of its strike inventory on more kinds of platforms. One path is loading a fraction of cells on every Aegis destroyer rather than concentrating Tomahawks on a few. Another is exploring containerized launchers ashore on the home islands and in the Ryukyus to create a land backstop. A third is fielding small, lower cost ships with a large number of launch cells that act as floating magazines while destroyers focus on sensing and air defense, a concept aligned with crewless warships at scale.

-

Practical at-sea resupply. The United States Navy has been evaluating methods to reload vertical launch cells from support ships in benign seas. Japan does not need a perfect solution to benefit. Even the ability to top off a handful of cells in a protected anchorage or a calm lee would keep destroyers on station longer. The enabling investments are modest and specific. Standardize crane fittings and safety interlocks across ordnance ships and destroyers. Train ordnance teams to a shared bilateral checklist. Pre-stage spare canisters, seal kits, and test cables on the resupply ship rather than sending them from shore each time. Certify a few anchorages with the right sea states and wind patterns for regular evolution.

-

Indigenous follow-ons. Tomahawk is a bridge to a Japanese ecosystem of stand-off weapons. The upgraded Type 12 surface to ship missile family, a long range land attack cruise missile program under Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, and a hypersonic glide vehicle for island defense will give Tokyo its own production base. Those programs will learn from Tomahawk in two ways. First, by adopting mission planning and data standards that let Japanese rounds ride the same kill web. Second, by designing reload and maintenance with Japanese shipyards and ordnance depots in mind from day one, complementing advances like Japan’s shipboard railgun.

Concrete implications for planners

- Plan for inventory by scenario, not by fleet size. A handful of days of high intensity operations could eat through dozens of Tomahawks. Japan and the United States should model realistic consumption rates for Taiwan Strait and East China Sea scenarios, then buy spares and canisters to those numbers, not to peacetime training budgets.

- Train the web, not just the ship. The most elegant combat system is useless if the command chain that approves a shot stalls. Embed Japanese watch officers inside American maritime operations centers and reciprocate. Run exercises that practice the full sequence from satellite detect to destroyer launch to battle damage assessment, with real timelines and legal checks.

- Protect the reload. Harden the piers and ordnance yards that reload destroyers. Practice rapid crane swaps and night evolutions. Pre-plan deception and traffic control to mask which piers are hot. Assign air defense and counter-submarine screens to the reload cycle as if it were a carrier.

- Use decoys and deception at sea. If Tomahawks ride in only a few ships, those ships become targets. Spread the rounds and use decoy emitters and false signatures to complicate enemy targeting. Pair Tomahawk shooters with ships configured to look exactly like them on radar and in the electromagnetic spectrum.

The 2025 to 2027 chart, simplified

- 2025. Initial deliveries begin. First wave of JMSDF crews complete Tomahawk handling and mission planning training with the United States Navy. Shipyard periods start on selected Kongo and Atago destroyers to add control consoles, software loads, and cabling for the weapon control system.

- 2026. First operational certification for a Japanese destroyer with Tomahawk. Additional hulls enter and exit modernization in a rolling sequence to maintain regional air defense coverage. Joint exercises shift from simulated shots to full mission rehearsals with live mission data packages and all the communications choreography, even if the missiles are not fired.

- 2027. Broader fleet availability. Stocks of Block V grow as production catches up. Maritime Strike Tomahawk employment concepts mature alongside air launched anti-ship missiles to produce layered salvos. Indigenous stand-off programs pass key tests and begin to plug into the same mission planning and data exchange standards.

These milestones are not a rigid script. They are a pace line. What matters is that each ship leaving the yard carries not only new hardware but a trained team and a reload plan.

What to watch in the next 18 months

- The first destroyer crew to complete full mission certification with American trainers, including the ability to accept a target package from offboard sensors and execute with minimal voice traffic.

- Evidence of regular Japanese ordnance handling drills at night and in poor weather, the telltale sign that reload tempo is becoming real.

- Chinese live fire exercises that pair anti-ship ballistic missiles with low altitude cruise missiles and electronic attack in the East China Sea, a rehearsal designed to stress Japanese and American air defenses while hunting the shooters that carry Tomahawk.

- Bilateral agreements that designate specific anchorages and ports as combined reload hubs with prepositioned gear and shared safety rules.

The bottom line

Tomahawk on Japanese destroyers does not guarantee victory. It guarantees options. It turns ships that already defend the fleet into instruments that can shape the opening moves of a crisis. It forces a potential adversary to disperse, to harden, and to spend. Most of all, it ties Japan more tightly into a combined web where the best sensor can feed the best shooter regardless of flag. That is what flips the strike balance. Not a single weapon, but a network that can think and act faster than anyone trying to break it.