New Glenn’s Mars Debut: Why NASA Bets on Flight Two

Blue Origin’s second New Glenn launch is set to send NASA’s twin ESCAPADE probes toward Mars. Here is why NASA chose a new rocket’s sophomore outing, how VADR changes risk, what ESCAPADE will study, and what success or a scrub would mean.

A second flight, a first leap to deep space

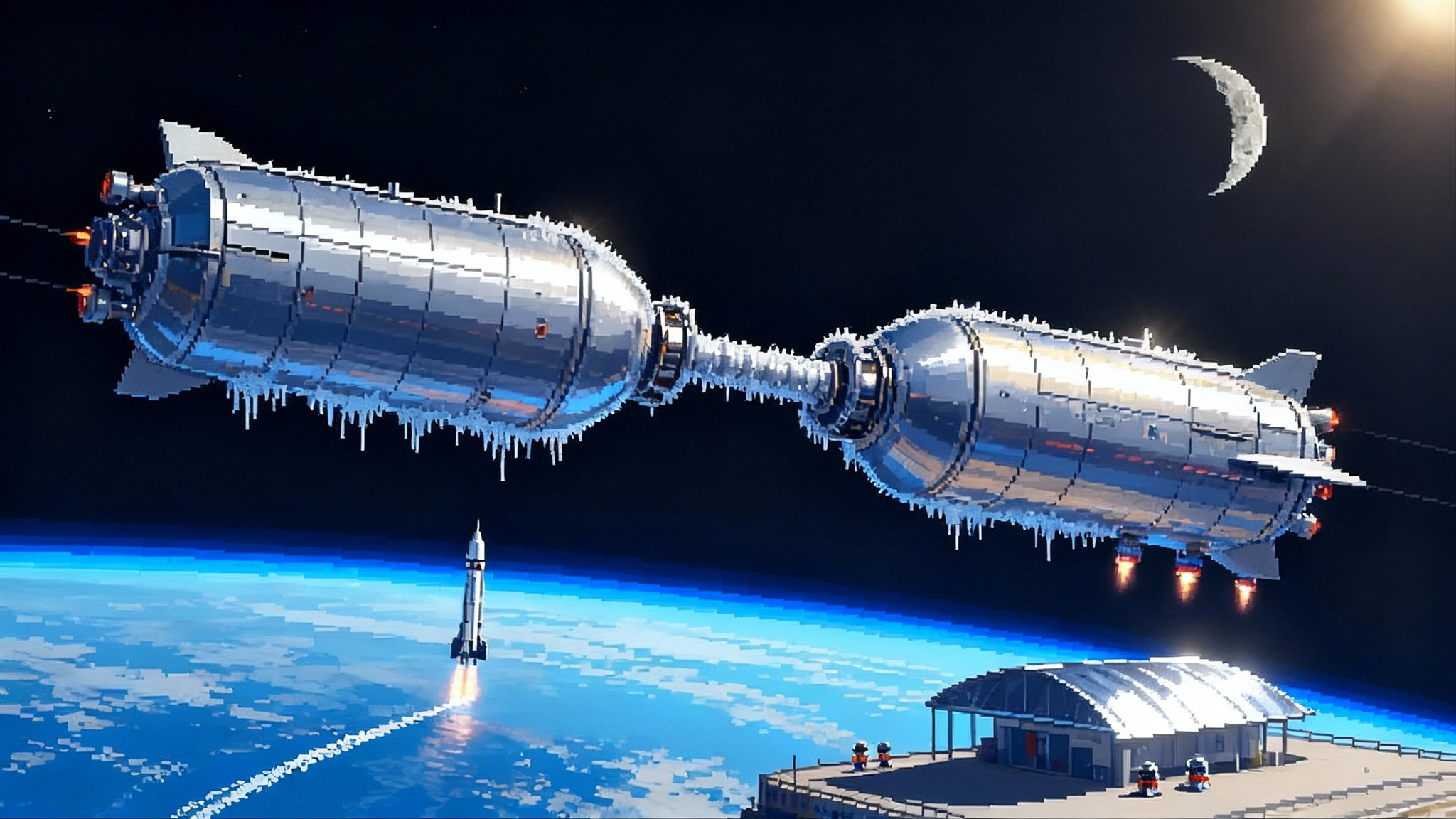

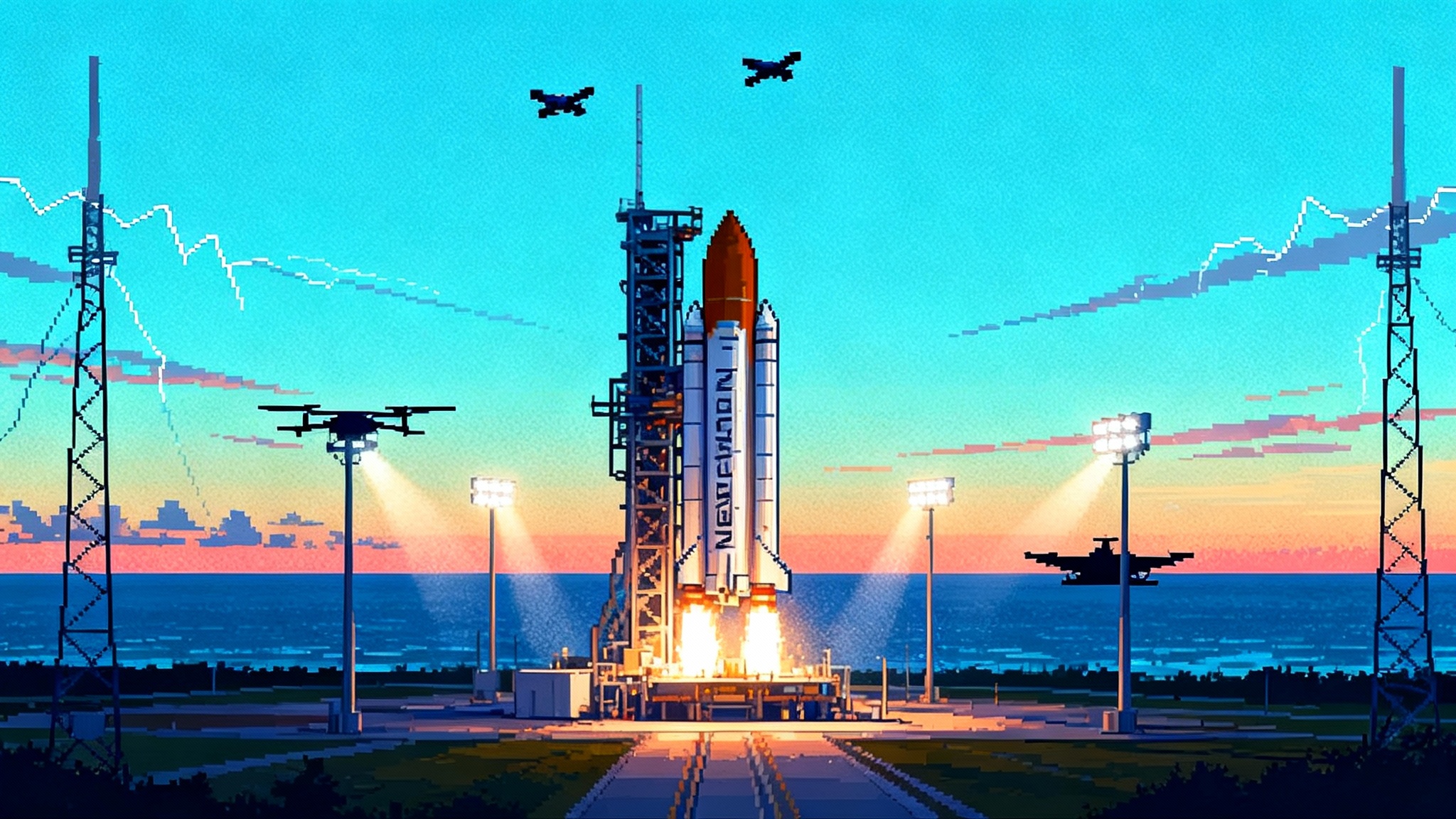

If schedules hold for late September 2025, Blue Origin’s New Glenn will ignite for its second-ever mission and its first shot at interplanetary space. Riding on top are NASA’s twin ESCAPADE spacecraft, identical small orbiters built by Rocket Lab to probe how the solar wind strips away the Martian atmosphere. This is a bold pairing: a brand new heavy lifter on only its second flight, and a Mars science mission that depends on a narrow launch window and a long cruise.

Why this match now? NASA wants more affordable, frequent rides to orbit for smaller science missions, and it is willing to accept carefully bounded risk when the payoff is meaningful. The agency selected New Glenn for ESCAPADE under its newer procurement framework for lower cost missions that can tolerate more risk, a program called VADR. NASA describes VADR as a way to buy FAA‑licensed commercial launches with a lighter level of mission assurance in exchange for lower prices and broader competition. Blue Origin’s task order for ESCAPADE came through that lane, which is why you see a Mars mission on a rocket that is still early in its career. For the essentials, NASA’s own contract announcement lays out the logic and the payload’s goals in plain terms, including the three instruments on each spacecraft and the plan for a roughly yearlong cruise to Mars followed by months of orbit shaping. Read it and you will see the shift in tone around acceptable risk baked right into policy and procurement language: selected New Glenn under VADR.

Why NASA is flying Mars science on New Glenn’s second launch

New Glenn reached orbit on its debut in January 2025, a milestone that cleared one of the biggest unknowns about the vehicle. Blue Origin did not recover the first stage on that first flight, but ascent performance and orbital delivery were the main objectives and those were met. NASA then had a choice. Either wait for a more mature flight history, which could push ESCAPADE into a later Mars window, or proceed on the second attempt to keep the science moving and to expand the pool of rockets that can credibly send small payloads toward other worlds. The second option won out.

There are practical reasons for this. ESCAPADE is relatively small and robust compared with flagship missions. Two identical spacecraft provide built‑in redundancy at the mission level. The science return depends on time in the right orbits more than on a heavy instrument payload, and the overall budget sits in NASA’s small missions class rather than the multibillion dollar range. In other words, this is precisely the type of mission VADR was designed to empower.

NASA also removed ESCAPADE from New Glenn’s maiden launch in late 2024 when prelaunch schedule risk began to threaten the window. That was not a vote against Blue Origin so much as a cost control decision. Fueling, defueling, and standing down a Mars payload can become its own expensive campaign. After New Glenn’s first flight proved ascent capability, pairing ESCAPADE to the second flight became a more comfortable bet.

How VADR changes the risk equation

VADR, short for Venture‑class Acquisition of Dedicated and Rideshare, is about buying launch services for payloads that do not need the very highest level of mission assurance. The contracts are fixed‑price and competed among a wider set of providers than NASA’s traditional Launch Services contracts. That matters for two reasons.

- It broadens access. New vehicles can start flying real NASA payloads sooner, which helps them build flight heritage and move faster down the learning curve.

- It tunes risk to mission value. Not every science objective needs the same level of assurance as a flagship mission. A small heliophysics or planetary mission can accept higher launch risk if the savings enable more missions overall.

ESCAPADE is a textbook case. Each spacecraft is about the size of a small refrigerator. The instruments are modest, proven types. The science is important, but the program is sized to tolerate the risk of a young launch system. VADR lets NASA express that tolerance in a clear, contractual way.

What ESCAPADE will actually reveal at Mars

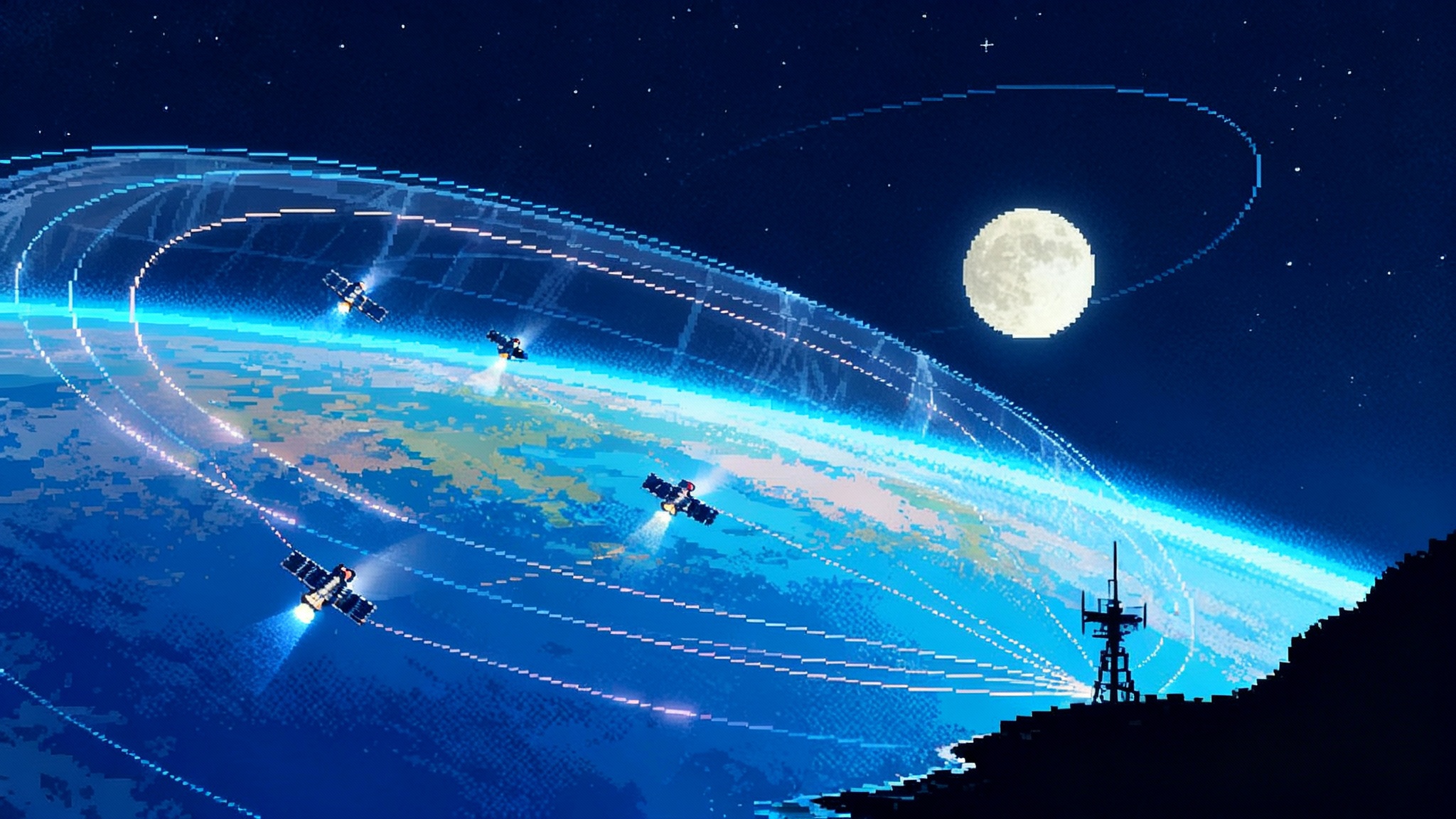

Mars once had a thicker atmosphere and surface water. Today it is cold and arid, with a thin atmosphere that offers little protection. One of the missing chapters is how the solar wind and Mars’ odd magnetic environment collaborated to strip that atmosphere away. ESCAPADE is designed to write some of that chapter.

Mars does not have a global magnetic field like Earth. Instead it has a patchwork, a hybrid magnetosphere influenced by crustal magnetic fields and the interplanetary magnetic field carried by the solar wind. That hybrid structure guides, accelerates, and sometimes ejects charged particles. Over long timeframes, those processes let atmosphere escape into space.

ESCAPADE tackles this with two vantage points at once. Each probe carries three instruments:

- A magnetometer to map the direction and strength of local magnetic fields.

- An electrostatic analyzer to measure the energies and composition of ions and electrons that are the currency of atmospheric escape.

- A Langmuir probe to sense plasma density and infer how solar ultraviolet radiation energizes the upper atmosphere.

Flying in formation, then transitioning to different orbits, the pair can disentangle what is changing over time versus what is different across space. In one campaign they will trail each other along nearly the same path, separated by minutes, to watch how the environment responds to sudden gusts in the solar wind. Later they will split, with one flying closer to the planet and the other higher up, sampling simultaneously across altitude. This two‑point strategy is how you turn snapshots into a movie.

The mission complements MAVEN, NASA’s earlier Mars orbiter that has been studying atmospheric escape for years. MAVEN provides long baselines and remote sensing of the upper atmosphere. ESCAPADE brings two in‑situ probes that can correlate shifts in magnetic topology with bursts of escaping ions in real time. Together, the data sets will sharpen models of how quickly Mars has been bleeding atmosphere and under what solar conditions the loss accelerates.

If the launch works, what it means

-

For commercial deep‑space access: Success would mark the first time a commercial heavy‑lift launcher other than Falcon Heavy has placed a NASA science payload onto an interplanetary trajectory. That matters. It signals that the market for deep‑space rides is expanding, not just for billion‑dollar flagships but also for nimble small missions. More providers and more fairing volume at competitive prices make creative architectures possible, from multi‑sat swarms to spacecraft with oversized booms and antennas that do not fit under a five‑meter fairing.

-

For Blue Origin’s recovery ambitions: New Glenn aims to land its first stage on a downrange platform, then refurbish and refly it. The company lost the booster on flight one and will try again on flight two. A clean landing would accelerate the reuse learning curve and eventually lower prices. A miss would not doom reusability, but it would lengthen the timeline to price parity with incumbents that regularly recover boosters. Either way, the interplanetary injection is the mission’s headline. If ESCAPADE is safely on its Mars trajectory, the primary objective is met.

-

For the Mars exploration roadmap: With Mars Sample Return in redesign and stretched budgets across planetary science, the cadence of Mars missions has been at risk. ESCAPADE helps keep the science drumbeat going and feeds a practical thread in NASA’s strategy. The agency has been rethinking how to return Perseverance’s cached samples to Earth and has asked for leaner architectures that hit earlier dates and lower costs. You can see that rethink in NASA’s own language about the program’s reset and search for faster, cheaper options: NASA is reworking Mars Sample Return. In that context, a small, on‑budget mission that flies on a new commercial rocket is a proof point for doing more with less while the flagship plan is rebuilt.

If the launch scrubs

Mars opportunities are not like a weekly rideshare to low Earth orbit. You get a window measured in weeks to aim for the right energy and geometry. A scrub or a few days of weather delays are normal for any large rocket, and the team will work through them. If delays push outside the late September window and into October, the team could still have options depending on the day‑by‑day performance margins and the trajectory they plan to use. If the window closes entirely, the most likely outcomes are a short stand down to prepare for the next viable departure opportunity or a pause while mission planners trade alternative trajectories that keep arrival and operations reasonable. None of those scenarios erase the work already done. The spacecraft are built, tested, and ready. The rocket has reached orbit once. A slip would mostly be about patience and logistics.

On the launch vehicle side, a scrub does not rewrite the story either. New Glenn is still in early flight tests. A conservative scrub that protects hardware is preferable to a rushed attempt that risks either the booster or the payload. Blue Origin’s underlying aim is to build a high‑cadence launcher with partial reuse. That takes a few flights. ESCAPADE on flight two is a sign that NASA judges the vehicle ready for real work, not a guarantee of perfect weather or flawless ground systems.

What to watch in launch week

- The launch window. Expect a multi‑hour window set by the trans‑Mars trajectory. If you see the team holding for weather in the first half of the window, that is normal while they steer for upper‑level winds and downrange sea states.

- Static fire and wet dress. If Blue Origin conducts a full countdown rehearsal or static fire, it will be a good check of ground systems since the debut flight. This is often scheduled a few days prior, but it is not a requirement on every mission.

- Booster landing attempt. The first stage will aim for an autonomous ship in the Atlantic. Recovery is not required for mission success, but a landing would be a big step for reuse.

- Fairing and payload integration photos. Look for the unusually large seven‑meter fairing. ESCAPADE’s twin spacecraft ride together under one fairing and will separate into a transfer configuration before the interplanetary burn.

- Upper stage performance. The second stage has to execute a precise burn for trans‑Mars injection. A clean staging event and on‑time ignition for that burn are two of the biggest moments in the mission.

- Separation and first contact. After separation, the spacecraft will check in through the Deep Space Network. Watch for confirmation of power positive and thermal stability on both Blue and Gold.

- Trajectory update. Within hours to a day you should see a note that the spacecraft are on their planned trajectory, either nominal or with a small correction scheduled. That is when everyone can exhale.

The bigger picture

In a year when planetary science is juggling tight budgets and a replan of its most ambitious project, a successful ESCAPADE launch would be a welcome proof that small, smart missions can still move. It would also mark a turning point for Blue Origin. Reaching orbit once is a debut. Delivering a NASA payload onto an interplanetary path on flight two is validation.

It also enlarges the market for deep‑space rides. When more rockets can handle interplanetary injection, planners can mix and match launch providers, spacecraft buses, and innovative mission designs. Think clusters of small orbiters that map a planet’s environment in stereo, or single‑launch missions that carry outsize booms, antennas, or even small landers under spacious fairings. Competition pulls price curves down and opens design space up.

If the mission slips a few days, it is not a referendum on any of that. Launch operations are a chain of thousands of details that must line up. The smart money is on patience and process. If the second New Glenn lifts off, nails its burns, and sends two small explorers outward, it will have done more than light up the Florida sky. It will have widened the lane for commercial deep‑space access and given Mars science another set of eyes to watch how a world loses air.

That is a useful result in any budget season, and a timely one as the community writes the next chapter of Mars exploration, from small explorers to the eventual return of the rocks Perseverance is caching today.