Replicator’s Quiet Breakout: Mass Arrives in the Pacific

Replicator moved from speeches to shipments. By May, INDOPACOM was taking deliveries. By September, Replicator 1.2 added the Enterprise Test Vehicle and maritime USVs, with software that survives jamming. Here is how the next 12 months turn quantity into deterrence.

The quiet flip from slide deck to supply line

For eighteen months, the Department of Defense’s Replicator initiative was about speeches, budget lines, and guarded hints. In 2025 it quietly crossed a threshold. Deliveries to U.S. Indo-Pacific Command picked up in May, and by early September officials and industry were talking about real numbers, real contracts, and real units in the field. The second tranche, Replicator 1.2, added the U.S. Air Force’s Enterprise Test Vehicle and new maritime systems, along with software that hardens autonomy under jamming. The result is not a single headline system, but a repeatable pipeline for quantity.

If you want one document that captures the gear shift, read the department’s Replicator 1.2 announcement. The signal is clear: hardware plus software, at scale, on the clock.

What INDOPACOM actually received in 2025

Think of Replicator as a family, not a product. In 2025, four strands matured in parallel:

-

Air-delivered effects. AeroVironment’s Switchblade 600 loitering munition moved from committee rooms to unit inventories. It is not a silver bullet for long-range fights, but as a precision strike round it plugs holes in the kill chain inside island arcs. The Air Force’s Enterprise Test Vehicle added a different lever: a cheap, fast airframe you can build by the dozen to test sensors, seekers, and guidance under real conditions, then push successful variants to production. This momentum echoes the USAF loyal wingmen tests.

-

Maritime uncrewed surface vessels. The Defense Innovation Unit’s small USV push and Navy programs fed craft that can loiter, tow sensors, deliver decoys, or act as small shooters. Because these boats are attritable, commanders can send them where they would never risk a crewed ship.

-

Company-level small drones. The Army’s picks, including Anduril’s Ghost-X and Performance Drone Works’ C100, focus on reconfigurable payloads that let maneuver units switch roles in minutes, from reconnaissance to target handoff.

-

Software that survives a fight. Replicator 1.2 funds integrated enablers for autonomy and resilient command and control. This is the connective tissue that turns scattered robots into a team when the spectrum gets ugly, a theme that pairs with NGJ Mid-Band enters service.

By September, one independent account summarized progress in plain terms: hundreds already delivered, thousands on contract, with a pipeline still spooling up. That framing is captured in an external report noting “hundreds” to warfighters and “thousands more on contract” as Replicator shifted from central sprint to service-led transition. See the context in hundreds delivered and thousands on contract.

The bottleneck is not launchers

It is tempting to count tubes and launch rails and declare victory. That would be a mistake. The hard problem is not putting a small aircraft or boat into the air or water. The hard problem is getting dozens to hundreds of those assets to sense, decide, and act when the radios are jammed, the GPS is spoofed, and the network is partially broken.

Three things matter most over the next year:

-

Mesh communications that degrade gracefully. Imagine a backpack full of walkie talkies that can all trade roles. When one node drops, the others reach around it. Replicator is funding radios that can hop between commercial and military waveforms, opportunistically borrow satellite links, and still pass critical messages peer to peer when nothing else works. The metric that counts is not peak bandwidth on a clear day. It is message delivery probability under jamming and clutter.

-

Electronic warfare hard autonomy. A drone that freezes when it loses data is a liability. A useful one follows a commander’s intent and local rules of the road when cut off. That means onboard maps that update without connectivity, vision and electronic support measures to detect spoofing, and behavior trees that prevent friendly fire while still making progress on the mission. It also means logging every choice so humans can review and tune tactics instead of guessing what went wrong.

-

Rapid tactics, techniques, and procedures iteration. When units find a trick that works, they need to push it across the theater in days, not months. You need a place to post a recipe and a way for squads to pull it to devices in the field. You need a test harness to try a new formation or timing pattern in simulation at lunch, then in an instrumented range that night, while telemetry auto-generates a simple after-action card.

None of this is glamorous. All of it is decisive. In 2025, the services began treating autonomy like software, not like steel. That shift is the real breakout.

The INDOPACOM sprint rhythm

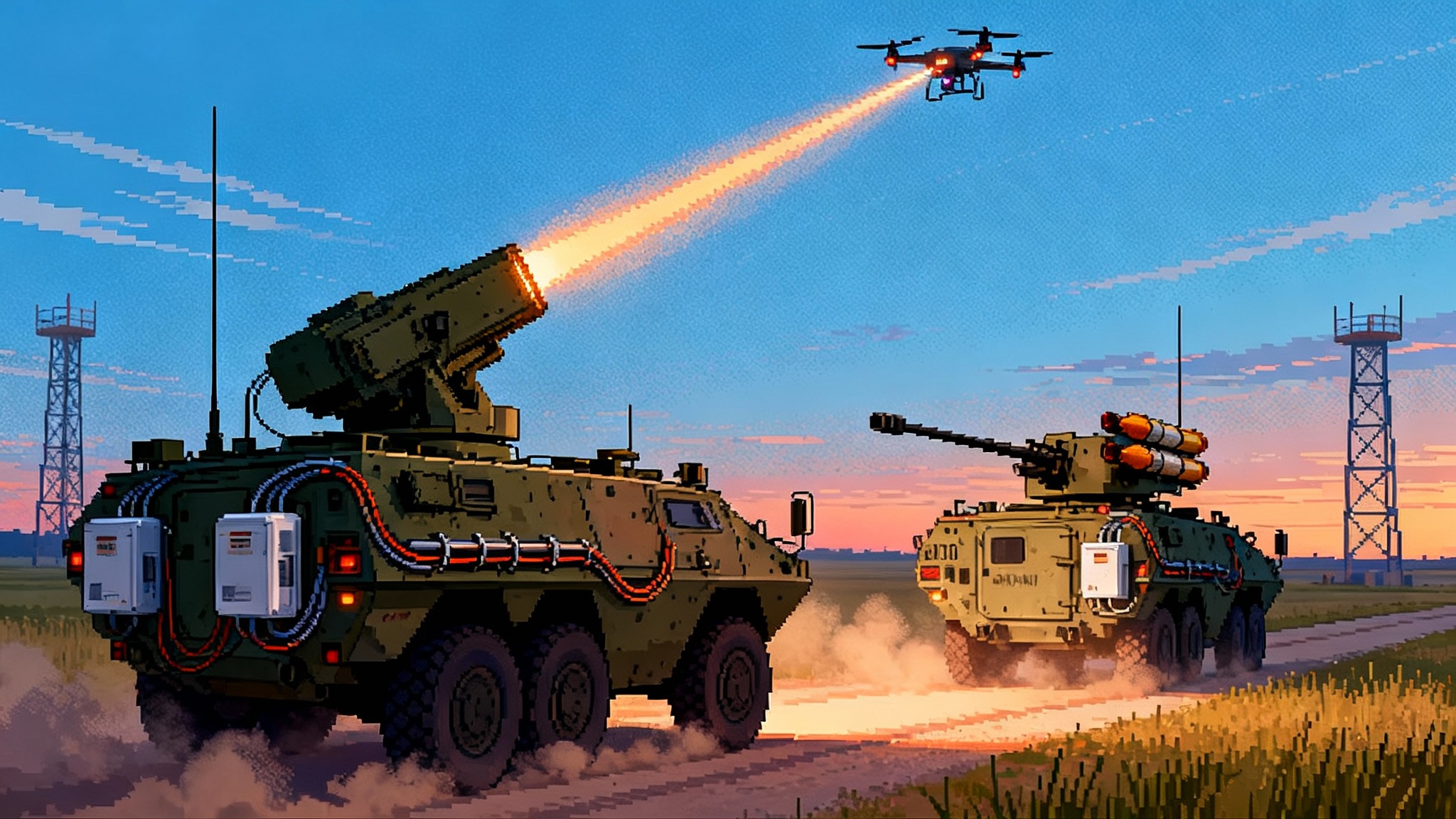

This year the command settled into a cadence. Each month, a representative kill chain gets exercised end to end, from find to finish, with different mixes of sensors, relays, and shooters. One month emphasizes maritime domain awareness with small USVs acting as pickets and decoys. The next stresses pop-up targeting with loitering munitions launched from trucks, aircraft, and austere island pads. Another run injects countermeasures, including heavy jamming, to force the autonomy stack to continue executing commander’s intent without constant babysitting. For the air defense side of the theater fight, see how lasers are changing the equation in Strykers flip the drone math.

Here is how these sprints look at ground level:

-

A Marine Littoral Regiment launches a wave of small USVs from a beachhead to seed a picket line. A Navy patrol craft carries relay buoys and a spectrum sensor to paint the jamming picture for everyone.

-

An Army unit rotates teams through a pop-up range where targets are exposed for seconds. Switchblade crews practice remote handoff between launchers as targets duck behind terrain, then fail over to visual navigation when GPS is denied.

-

An Air Force detachment runs Enterprise Test Vehicle airframes as sensor mules to try three seeker packages in parallel, using the same command tablet and the same datalink profile the unit will use in a real fight. The test aims to answer a simple question in a week: which seeker still scores hits when the jammer is turned up to 11.

The output is not a glossy demo reel. It is a small set of changed TTPs, a ranked list of bugs and missing features, and a tasker to units and vendors for the next sprint. This is how quantity learns.

Allied co-production moves from panel talk to factory floor

Mass without partners is brittle in the Pacific. The supply line is long, the targets are dispersed, and sovereign politics matter. The most concrete shift in 2025 happened in the water. Australia moved from prototype to production on large autonomous undersea vehicles while building a domestic supply chain that includes dozens of local companies, paralleling the momentum in AUKUS Ghost Shark undersea strike. That kind of allied manufacturing base does more than add units. It adds resilience, forward repair capability, and shared incentives to keep the pipeline funded.

Expect the same pattern to expand to small uncrewed surface vessels, sensor buoys, and relaunched commercial platforms. The logic is simple. If a partner can build a fishing skiff, it can build a small attritable USV with the right kit. If it can maintain small engines and outboards, it can repair and relaunch. The strategic payoff is not a few exquisite allied prototypes. It is a theater stocked with spare parts, trained maintainers, and interoperable control software that makes any nation’s contribution count inside a common kill chain.

What changes in the next 12 months

Replicator’s quiet breakout sets up a different kind of race in 2026. The bottlenecks are now specific and fixable. Here is what matters next, with concrete actions attached.

-

Unify datalink profiles across families. Success metric: a unit can swap a failed airframe with a different vendor’s bird and keep the mission plan, the control tablet, and the rules of engagement unchanged. How to do it: publish the minimum viable profile for control, health, and visual nav updates, require it in contracts, and prove it in monthly sprints by mixing fleets on purpose.

-

Push autonomy updates like phone apps. Success metric: a signed autonomy patch moves from lab to three forward locations inside seven days and is reversible if it misbehaves. How to do it: standardize packaging, define a fast track for safety and fratricide checks, and assign a small red team to try to break each patch before it ships.

-

Harden navigation without babysitting. Success metric: a drone completes its task in a GPS-denied bubble using visual landmarks and pre-briefed constraints. How to do it: mandate that every platform carry at least two independent nav modes, invest in low size, weight, and power vision processors, and train crews to set clear intent and boundaries so autonomy can act without surprises.

-

Treat mesh networks as a consumable. Success metric: when a jammer knocks out a satellite link, the mission continues with a degraded but functioning mesh using handheld radios, airborne relays, and boat-mounted nodes. How to do it: stock cheap relay nodes like batteries and run a weekly drill that simulates loss of primary links, then log and fix the routes that fail.

-

Build common payload kits. Success metric: the same warhead or sensor slides into three airframes and two boat types. How to do it: standardize electrical and data interfaces and publish 3D printable mounting hardware that local depots can produce on demand.

-

Close the sustainment loop forward. Success metric: a partner nation depot can diagnose a failed board, pull a spare from local stock, and return the platform to service inside 48 hours. How to do it: push test gear, publish simple troubleshooting trees, and attach a vendor field tech to each allied depot for the first six months.

What success by mid 2026 looks like

If Replicator uses the next year well, the picture in June 2026 will be different in ways that matter day to day. Here is a concrete scoreboard.

- Operational mass: 4 to 6 mixed squadrons of attritable air and surface systems in the first island chain, able to generate hundreds of sorties per week without a special exercise banner.

- Kill chain speed: find to finish for a moving maritime target under jamming, measured in single digit minutes using a mesh of small sensors and loitering effects.

- Cost discipline: a median attritable airframe or boat with payload under a set price point that a battalion commander will actually risk, with spares on theater shelves.

- Software rhythm: autonomy and networking updates landing on a two-week cadence with baked-in rollbacks, documented in a changelog crews read because changes tie to recent sprint results.

- Interoperability reality: a partner’s platform joins a U.S. mission on 48 hours notice using a shared datalink profile and mission plan format, with local operators trained to the same TTP.

- Deterrence signal: routine public releases of sprint results that show the ability to saturate a strait with small systems on short notice without revealing specifics, matched by quiet briefings to partners that lay out who brings what within a week of crisis.

How this rewires Pacific deterrence

The Pacific problem has never been about a single decisive duel. It is about distance, numbers, and time. Replicator’s payoff is to bend those factors. Small, smart, affordable, and numerous platforms cut the time between finding and finishing a target. A mesh that refuses to die under jamming stretches the adversary’s decision loop. Allied production of simple, swappable platforms shortens the distance for spares and repairs.

The deeper shift is cultural. When commanders know they can risk ten boats and twenty drones to protect a crewed ship, they make different choices. When a monthly sprint proves a new formation in a week, units try bolder tactics. When software updates land on a schedule, the burden of learning drops from heroics to habit. That is what turns a press release into operational mass.

This does not replace submarines, destroyers, or aircraft. It multiplies their reach. It does not end the cat and mouse of electronic warfare. It embraces it and still completes the mission. If 2025 was the year Replicator stopped talking and started shipping, then 2026 is the year the theater learns to ride the wave.

The path from here is not mystical. It is a to-do list. Keep the sprint cadence. Standardize what matters. Let units and allies co-create the TTP they will live with in a crisis. Fix the datalinks. Ship the software. Stock the spares. If the department keeps its hand on those levers, the quiet breakout of 2025 will look, in hindsight, like the moment deterrence in the Pacific started to scale.