Mach 5 on Wheels: Blackbeard Comes to HIMARS

An October Army-Navy push put Castelion's Blackbeard on a path to ride legacy launchers like HIMARS. Here is how truck-mobile, lower-cost hypersonic rounds could flip magazine depth, A2/AD math, and Pacific deterrence by 2027.

The October pivot: hypersonics meet trucks

On October 24, 2025, Castelion announced integration awards on October 24, 2025 for Blackbeard, the company's hypersonic strike weapon, with live-fire demos to follow. The disruptive idea is simple: instead of parking hypersonics on bespoke, few-in-number launchers, make a Mach 5 plus round that rides on the U.S. Army's common wheeled launchers. In plain terms, put hypersonic speed on trucks.

Blackbeard's pitch is more than speed. The promise is manufacturability and scale built on a build-test-learn cadence that aims to turn a boutique technology into a repeatable product. If the Army and Navy integrate a seeker-guided hypersonic round onto operational platforms and fire it from the same families of trucks and pods already in the force, the implications ripple across cost, logistics, doctrine, and deterrence.

Why putting hypersonics on legacy launchers matters

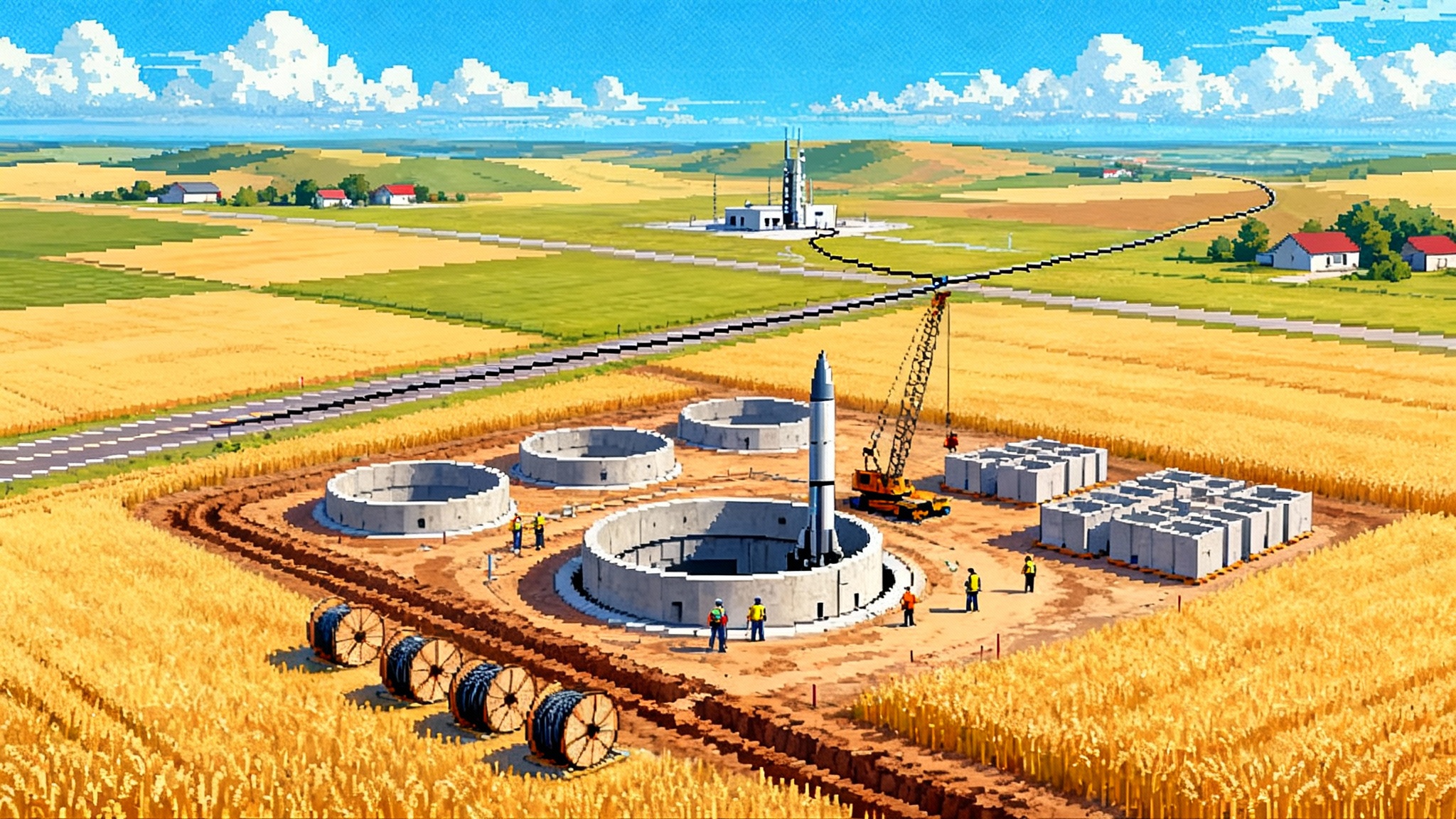

The past decade taught a hard lesson. Ultra high end, limited inventory hypersonics can be technically impressive yet operationally brittle. They are costly, fielded in low quantities, and often live on specialized launchers that are hard to hide and harder to sustain in a fight. A mobile launcher like the High Mobility Artillery Rocket System, or HIMARS, and its tracked cousin in the Multiple Launch Rocket System fleet, offers something different: a familiar vehicle with a known training pipeline, a mature supply chain, and the ability to shoot and move in minutes.

If Blackbeard rides in a canister that plugs into existing fire control, a unit can disperse across many small sites, fire at long range, and relocate immediately. That makes the launcher harder to find and kill and creates many more aim points for an adversary. It also taps the Army's existing sustainment base, which compresses the time and money needed to field new capability. Reuters reported that Castelion is targeting unit costs in the hundreds of thousands per round and thousands of rounds per year at full rate production, a very different cost posture than exquisite, single mission weapons.

The magazine problem, explained with trucks

Think of long range fires like a boxing match. It is not just who can throw the hardest punch, it is who can throw the most accurate punches for the longest time without getting hit. In the fires world that means magazine depth and survivability. A unit that can keep launching precision rounds while evading counter fire will usually win the exchange.

Legacy rocket artillery already solved part of this puzzle with podded munitions and standardized reload drills. Truck pulls in, crew swaps canisters, truck moves out. If a hypersonic all up round can ride in a compatible canister, the math shifts. You do not have to invent new reload gear, new forklifts, or new training. You repurpose what tens of thousands of soldiers already know how to do.

That is where the cost curve flips. Instead of buying a few hyper expensive shots and hoping every one lands, commanders can plan for dozens of shots per battery, with reloads staged on the same trucks and trailers the Army already fields. More shots per day mean more windows to exploit fleeting targets and more resilience when an adversary attempts to saturate defenses.

Dispersed basing is a feature, not a workaround

Truck mobile launchers unlock an operating concept that favors many small footprints over a handful of big ones. A battery can split, hide among civilian traffic, stage from austere airstrips, or pair with Army watercraft and small landing vessels to hop between islands. Because the launcher is common and the ammunition rides in sealed canisters, units can stockpile reloads and rotate crews the way they already do for rocket artillery. The result is a force that is constantly moving and hard to pre target.

In archipelagic regions, this looks like a relay race. One team sets up and watches for target quality data, another team waits under camouflage with reloads, and a third team is already moving to the next site. If an adversary strikes where a battery just fired, they hit an empty patch of ground. If they try to hunt launchers with drones, the launchers can burst from cover, shoot, and melt away, while decoys complicate the picture. For a naval hypersonics backdrop, see our look at the Navy CPS test timeline.

Plugging hypersonics into the kill chain

Hypersonics are only as useful as the kill chain that feeds them. The Army's Integrated Battle Command System, or IBCS, is designed to fuse sensors and shooters into a single fire control network so units can connect the best available radar to the best available weapon. On top of that, Joint All Domain Command and Control, or JADC2, aims to pass targeting quality data across services at machine speed. In practice, a Navy surface search radar or a maritime patrol aircraft could provide a track, an Air Force platform could refine it, and an Army launcher could fire.

Two technical choices make the difference:

- Use a seeker and data link that accept midcourse updates from joint networks so you can fire on a coarse track and refine in flight.

- Design the canister and launcher interface to be backward compatible with widely fielded truck launchers, preserving mobility and training continuity while specialized launchers mature in parallel.

For how space sensors can tighten this loop, see Golden Dome's space shield build out and the role of rapid launch in Victus Sol's responsive space milestone.

The Pacific problem set: changing A2/AD math

Anti access and area denial is a numbers game. An adversary tries to make a large region deadly for surface ships and aircraft by saturating it with long range sensors and layered defenses. The defender needs enough survivable fires to hold key nodes at risk anyway. Put hypersonic rounds on common launchers and the defender's playbook expands.

- More nodes. A hypersonic battery can split into many small teams, each able to contribute a round or two and then displace. That multiplies the number of potential firing points the adversary must surveil and target.

- More shots per day. Sealed canisters and truck reloads mean crews can sustain a higher firing cadence. A distributed force can keep chipping away at radar sites, air defense nodes, logistics hubs, and transport chokepoints.

- More dilemmas. If hypersonics are affordable, commanders can consider using them against moving targets that previously would have been reserved for aircraft or ballistic missiles. That forces an adversary to guard more things, more often, with fewer safe havens.

The goal in the Pacific is not to win with one knockout punch. It is to create persistent, credible risk to the key systems that enable an adversary's long range kill chain, while keeping launchers alive. Hypersonics on trucks, tied into joint sensors, moves that from theory toward practice.

What the October awards really signal}

Integration contracts do not guarantee fielding, but they expose the friction points and who intends to remove them. The late October Army and Navy moves signal four priorities:

-

Prove launcher compatibility. A live fire from a standard Army truck family is the fastest path to operational confidence because it validates fire control, canister handling, crew procedures, and post shot survivability. Reuters notes the Army's interest in adapting mobile launchers and outlines cost and scale targets.

-

Show seeker performance on hard targets. The weapon must hit moving or hardened targets in defended airspace. That is the line between a tech demo and a tool a brigade commander can schedule into a day's fight.

-

Demonstrate the networked kill chain. A Blackbeard shot should accept joint sensor cues over the same command systems the Army is fielding for air and missile defense.

-

Validate production at scale. A hypersonic weapon has to be built like a product, not a prototype. That means repeatable manufacturing, instrumented test stations, quality control gates, and suppliers that can deliver to takt time.

What 2026 to 2027 pilot fielding would require

If the services want an early operational capability in the 2026 to 2027 window, three lines of effort must mature in parallel: production, doctrine, and policy.

Production

- Lock in the production line now. Hypersonic propulsion and thermal protection are sensitive to small process changes. The antidote is a stable line with instrumented stations, automated inspection, and a digital thread from design to factory quality data.

- Qualify the canister as a product. The canister is the interface between logistics and lethality. It must be safe to handle in heat, cold, and salt spray, resilient to rough transport, and tolerant of field knocks without hidden damage.

- Build for field maintenance. Replaceable line replaceable units are better than depot only modules for a system intended to live at small austere bases.

Doctrine and training

- Treat hypersonics like a precision service, not a trophy. Putting shots on trucks means battalion and brigade staffs will schedule hypersonic fires next to rockets and missiles.

- Rehearse the networked shot. Units should train end to end... from a maritime radar track to a launcher receiving a target quality message through IBCS to a successful shot and immediate displacement.

- Write the reload playbook. In a dispersed posture, the most complex minutes are the minutes after firing. Define rally points, decoys, and dummy emissions patterns so that crews can reload without drawing a missile to their next location.

Policy and export controls

- Decide the allies and the envelope early. Hypersonic systems fall under strict export controls. If the United States intends to share a ground launched hypersonic with close allies, define approved seekers, ranges, and data links now.

- Protect the right crown jewels. The seeker, guidance software, and thermal protection should receive the tightest controls. The canister and launcher interface standards can be more widely shared to accelerate partner training and logistics.

- Use Foreign Military Sales to shape the network. If export is allowed, tie sales to participation in common digital kill chain standards.

How this could shift deterrence by the end of the decade

Deterrence is the art of creating predictable costs for aggression. A force that can quietly disperse dozens of launchers across islands, pull joint target data through a common network, and fire hypersonic rounds repeatedly from canisters a crew already knows how to handle will be harder to dislodge and harder to intimidate. It will also be more credible to allies who must wager their bases and ports on U.S. staying power.

Watch these three milestones in 2026 and 2027

- A HIMARS family live fire with a seeker equipped hypersonic that rides an operational fire control interface and closes on a moving target.

- A networked shot that showcases cross service cueing through fielded command and control.

- A production audit that proves repeatability at scale with short takt time, stable yields, and supplier depth.

The smart takeaway

The Army Navy integration push for Blackbeard is not just another contract notice. It is a credible shot at making hypersonic speed routine at the tactical edge. If the services keep the focus on compatibility with common launchers, clean interfaces to IBCS and joint networks, and a production line built for repetition, they will do more than field a faster missile. They will change the geometry of the fight and the economics behind it. In an era defined by sensors that can see you and defenses that can find you, the winning move is not a single silver bullet. It is many fast, precise, affordable shots from places the enemy did not expect and cannot pre target in time.