Sentinel Reset: How the 2025 Overhaul Rewrites the ICBM Plan

After a historic cost breach, the LGM‑35A Sentinel is being rebuilt in 2025. This analysis unpacks what the reset changes, how timelines shift, and which FY26–FY27 decisions will speed or stall the reboot.

The reset arrives

In July 2024 the Department of Defense certified that the Air Force’s LGM‑35A Sentinel could continue after a critical cost breach under the Nunn‑McCurdy statute, but only with a fundamental restructure. The certification rescinded the program’s previous Milestone B and directed a rebuild of the plan, management, and cost controls. The official estimate from the Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation office rose to 140.9 billion dollars, an increase of 81 percent from the 2020 baseline. In plain language, the government said keep going, but change how you are doing it, and prove the numbers this time. That determination is documented in a Pentagon release now anchoring every Sentinel discussion, see the DoD review and certification.

By early 2025, the Air Force paused parts of the command and launch work and revisited assumptions about the hardest and most expensive elements. Officials publicly acknowledged what contractors had been signaling for months. The old plan to refurbish hundreds of Cold War silos and to swap out miles of buried copper and fiber while keeping a tight schedule was not just risky. In many places it was unrealistic. A test conversion in California surfaced unknown site conditions that multiplied cost and time. By May, the service said outright that many locations will need new launch facilities rather than conversions, a shift with profound implications for schedule and community planning, as reported in Air Force says new silos are needed.

Think of Sentinel as a stool with four legs: the missile, the silos and launch centers, the command and control that ties it together, and the rocket motor industrial base that feeds production. The 2025 restructure touches all four and changes how the program advances through the late 2020s.

What actually changes in 2025

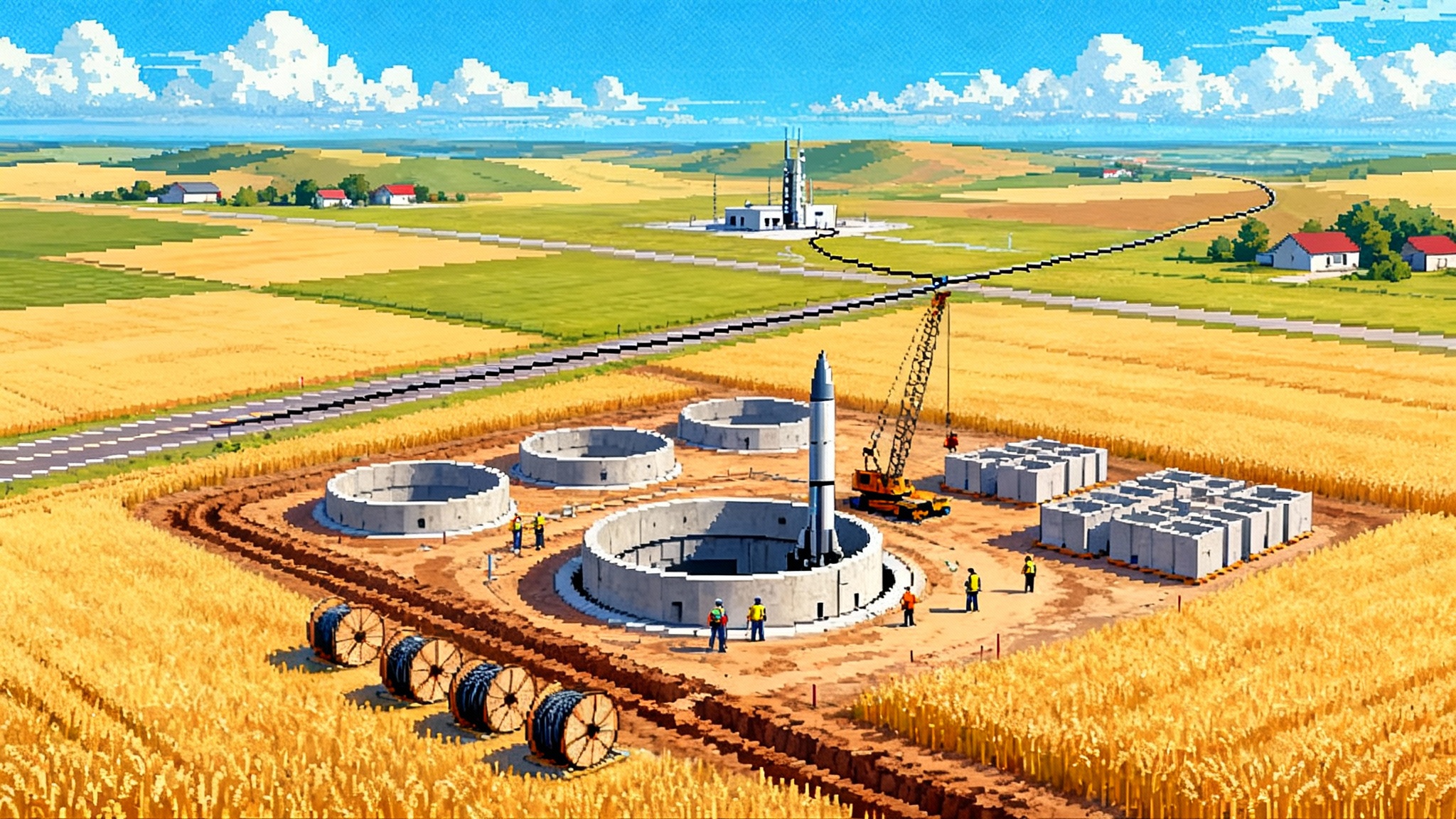

1) Silo recap becomes rebuild

The original concept was to rehab Minuteman III silos and launch centers across wide swaths of Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, Nebraska, Colorado, and California. That path sounded efficient. Use the holes you have. Replace the guts. Pour some new concrete. Pull and replace cables across thousands of miles of rights‑of‑way. Then reality intervened. Old facilities are like century homes. Once you open a wall, you discover wiring you did not expect, pipes where they should not be, and foundations that were never documented. Multiply that by 450 sites.

In 2025 the Air Force signaled a pivot to building many new silos and standardizing the design so crews can repeat the same steps with fewer surprises. This reduces engineering churn and lets civil contractors sequence work like highway crews, moving in a wave with proven equipment and methods. It also concentrates environmental permitting on a known design, rather than a patchwork of one‑off fixes. The near‑term cost looks higher, but the variance is lower, which matters for avoiding the cycle of redesigns that drove the breach.

For the missile fields, this feels like a highway rebuild, not a pothole patch. Counties will see longer construction windows, more heavy equipment, and steadier employment. Utilities will get clearer schedules for trenching and backfill. Landowners will get firmer easement timelines. The hard part is mobilization, since earthwork season in the Upper Midwest is constrained by winter. Expect a rhythm of spring survey, summer dig, fall fit‑out, and winter interior work.

2) Digital engineering that matches the dirt

Sentinel was always pitched as a model‑based program. The reset asks for something more disciplined. Digital engineering only helps if it matches real conditions. The new approach pushes for site‑specific digital twins, each tied to actual ground scans, utility maps, and as‑found drawings. The point is to stop discovering problems with backhoes and start finding them in models.

That means Lidar of each facility, borehole data for geotechnical layers, and point‑cloud models that designers and civil crews both trust. It also means configuration control. A cable routing change logged in the model must show up in procurement and in the field bill of materials. If this sounds obvious, it is. But on a program with hundreds of nearly similar sites, “nearly” is what kills you. The 2025 reboot is trying to turn “nearly” into “exactly” before concrete is poured.

Two actions will matter most:

- Lock a standard launch facility design early, then create a controlled menu of allowed variations. Think of it like a house plan with a few approved options, not a custom build every time.

- Tie the model to field acceptance. A contractor cannot claim a pour unless the digital twin for that site is updated and approved. Payment follows the model, not a paper stack.

3) Command and control hardening becomes a first‑order driver

The Nunn‑McCurdy review highlighted that most cost growth sat in the command and launch segment. That is the web of launch centers, communication lines, encryption, human‑machine interfaces, and the process to convert a field from Minuteman III to Sentinel while maintaining a credible deterrent every day of the process. It is not glamorous, but it is where complexity lives.

In the reset, expect three practical shifts:

- More prefabrication. Hardened shelters, vaults, and cable terminations built in controlled facilities and shipped to the field reduce rework and weather delays.

- Cyber and electromagnetic pulse protections specified earlier. Equipment racks, fiber routes, and power conditioning sized and shielded from the start. Retrofits later are far more expensive.

- Fewer parallel conversions at once. A slower but more predictable fielding wave that keeps maintenance crews trained and minimizes the number of partially converted sites, which are the most fragile.

The payoff is reliability. Nuclear command, control, and communications, often called NC3, is the nervous system. The missile is the muscle. The reset shifts money and attention to the nervous system, which is where the last plan underestimated risk. For a broader context on integrated fires and command networks, see IBCS breakout moment in 2025 and how SDA’s constellation rewires defense.

4) The solid rocket motor industrial base gets real attention

Big solid rocket motors are a bottleneck, and not just for Sentinel. Northrop Grumman produces large motors in Promontory, Utah. L3Harris, which owns Aerojet Rocketdyne, is expanding solid rocket motor capacity in Arkansas and Virginia. The Pentagon has started using Defense Production Act tools to backfill suppliers, and new entrants like Anduril and Ursa Major are moving into solid propulsion for tactical systems. The Sentinel reset forces a basic question. Can the nation produce enough large boosters on the cadence a strategic program needs while also feeding a surge in tactical rockets and hypersonic boosters?

Here is the practical answer emerging in 2025. The Air Force will long‑lead order materials for the first production lots, smooth the demand curve so casting pits are utilized but not overbooked, and avoid overlapping too many strategic and hypersonic test campaigns. The goal is to prevent a traffic jam at the exact few factories that mix propellant, wind cases, and cure segments. L3Harris’s visible expansion and similar moves by others show the supply base is adding capacity, but the ramp is measured in years, not months. The competition for materials and people will also shape programs like JASSM XR and the missile wave.

How the reset changes the timeline through the late 2020s

Before the breach, the program aimed at an initial operational capability by the end of the decade. After the review, officials described a delay of several years and rescinded Milestone B to replan. In 2025, leadership and industry sources have discussed a new Milestone B target in the 2027 window. First flight dates are under reassessment as the test plan is re‑sequenced. If the silo strategy locks in during 2025 and 2026, and if solid motor qualification stays on track, initial fielding would slide into the early 2030s.

For the late 2020s, the practical outcome is this:

- Minuteman III remains the day‑to‑day deterrent. The Air Force will extend components, manage aging test schedules, and husband spares.

- Early Sentinel articles focus on propulsion, guidance, and ground system integration rather than immediate operational readiness. Expect more incremental ground testing and fewer high‑visibility flight events until the restructure is certified.

- Field work shifts from conversion prep to new construction preparation, which means heavier environmental reviews, more utility coordination, and predictable but longer build cycles.

The timeline risk bars are clear. The slowest bar is civil construction in harsh climates and on private land. The second is command and control integration, which involves both hardware and cyber accreditation. The third is propulsion, where qualification testing is steady but cannot be rushed. The reset prioritizes certainty over speed, which is what a strategic program needs after a cost breach.

Risk, reframed

Risk did not disappear in 2025. It moved and became more visible.

- Technical risk: New silos cut retrofit surprises but add green‑field risk. The mitigations are standard design, repeatable sequences, and prebuilt modules. Digital twins tied to payment reduce change orders.

- Industrial risk: The nation’s solid rocket motor base is expanding, but strategic boosters compete with tactical rockets and hypersonic programs for mixers, castings, and people. Clear slotting of production runs across programs is essential.

- Programmatic risk: After the Milestone B rescission, the program must re‑earn trust with defensible schedules and independent cost checks. Quarterly earned value is not enough. The measures that matter are site‑level progress against the digital model and propulsion qualification burn‑downs.

A useful metaphor is air traffic control. Before 2025, Sentinel tried to land too many flights at once on a short runway. The reset adds runway length by building new silos and adds controllers by forcing better modeling and sequencing. The cost went up. The chance of a mid‑air went down.

What it means for deterrence posture in the late 2020s

Deterrence is not a single missile. It is a message that the system works every day. In the late 2020s, that message rests on three pillars.

- Minuteman III sustainment: Keep reliability high without exhausting the fleet with too many test pulls. Expect care in flight test pacing and targeted component refreshes where aging bites hardest, such as guidance packages and cable plant.

- NC3 resilience: The reset pushes money into hardened communications, power conditioning, and cyber defenses at launch control centers. That improves credible response even before Sentinel is fully fielded.

- Visible construction and community engagement: New silos and launch centers are not just holes in the ground. They are signals to adversaries and reassurance to allies that the land leg of the triad is being modernized with seriousness. Counties in Montana, Wyoming, and North Dakota will see sustained activity. That is governance as much as engineering.

The bottom line for posture is steady capability rather than new capability. The next few years are about replacing weak links in the chain while the new chain is forged.

Ripple effects you will feel elsewhere

The solid rocket motor question reaches into almost every other high‑end missile program. Hypersonic weapons that rely on solid boosters to launch their glide bodies are drawing on many of the same mixers, case winders, and nozzle fabricators. So are production lines for long‑range conventional missiles. Two consequences follow.

- Hypersonic test cadence depends on booster availability. If strategic segments reserve casting pits for Sentinel at key moments, hypersonic programs will need to shift test windows or use alternative suppliers. This forces a portfolio view that prioritizes readiness over concurrent peaks.

- Materials and people are strategic. Carbon‑carbon, insulation liners, bonding agents, and the technicians certified to handle them are the real chokepoints. That is why you are seeing investments in new factories and automation for casting and cure steps. The goal is more throughput with the same quality controls.

There are also local effects in the missile fields.

- Labor markets tighten. Heavy equipment operators, electricians with high‑voltage credentials, and fiber splicers will command premiums. Base commanders, county planners, and prime contractors will need early hiring pipelines and training partnerships with community colleges.

- Roads and utilities see stress. Sequenced construction and utility coordination plans are essential to avoid flooding a county with trucks one month and leaving it idle the next. A rolling wave, by county and by utility corridor, will work better than a Big Bang start.

- Permitting becomes a program unto itself. New silos mean fresh environmental assessments, cultural resource consultations, and water management plans. The more standardized the design, the smoother these approvals go.

The FY26 to FY27 decisions that will speed or stall the reboot

Congress and the Department of Defense have two budget cycles to prove the reset is more than a memo. The choices below are specific levers with clear outcomes.

- Lock the standard launch facility design in FY26, and fund long‑lead orders for repeatable hardware. Why: Vendors can tool up for identical parts and prefabricated modules, which accelerates field work in 2027 and 2028. How: Tie funds to acceptance of the digital model for the standard site and release batch contracts for pre‑cast, vaults, and cable assemblies.

- Segment the command and launch work into regional civil packages with clear interfaces, and keep Northrop Grumman focused on integration and missile performance. Why: Local firms can move dirt and pour concrete faster when the scope is clear, while the prime reduces overhead on commodity construction. How: Use multiple award task order contracts keyed to the standard design, with earned value tracked in the model.

- Dual‑source critical solid rocket motor subcomponents by FY27. Why: Nozzles, liners, insulation, and case materials are single points of failure. How: Place small but continuous orders with a second qualified supplier and use government‑owned test articles to prove interchangeability.

- Fund a digital twin baseline and enforce configuration control with milestone payments. Why: The model becomes the single source of truth. How: Condition payments on model updates and field validation at each site, audited by an independent verification team.

- Approve a phased flight‑test plan that front‑loads risk on the ground. Why: Fewer flight test surprises and less public drama. How: Increase ground test complexity in 2026 and 2027, then fly a smaller number of mission‑representative events in 2028 with fully integrated subsystems.

- Schedule independent cost and schedule reviews every six months until the new Milestone B in 2027. Why: Avoids optimism bias and surfaces problems early. How: Task the Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation office and the Government Accountability Office to publish synchronized assessments that both committees can read before marks.

What to watch if you are a supplier or a community leader

- Has the Air Force frozen the standard silo design and begun ordering long‑lead items at scale by mid‑2026? If yes, construction will start to look like a pipeline rather than a patchwork.

- Are propulsion qualification tests hitting their burn‑down plan without re‑work? Quiet success here is the best signal that production can scale.

- Did the program re‑enter Milestone B in the new 2027 window with an executable schedule? That means the reset stuck and that risk is trending down rather than being pushed right.

- Are county and state permits being issued in predictable batches? A steady cadence of approvals is a leading indicator of field progress.

The upshot

The 2025 Sentinel reset trades speed for certainty. It replaces a patch‑and‑pray approach to Cold War infrastructure with a build‑it‑right plan that uses standard designs, real digital twins, and a tighter grip on the command and control backbone. The bill is larger and later than anyone wanted. The benefit is a path that is actually walkable.

For the rest of the decade, deterrence rests on a disciplined Minuteman III sustainment plan and visible ground work that convinces adversaries we can field a new system without drama. The industrial base will be stretched, but the expansions now underway and smarter scheduling can keep strategic and hypersonic programs from colliding. The true test will come in the FY26 and FY27 budgets, when Congress and the department decide whether to fund standardization, dual‑sourcing, and the model‑first discipline that this program now needs.

Build the runway first. Then land the plane. If those choices hold, Sentinel’s reboot can turn a painful breach into a credible modernization story that carries into the 2030s without another reset.