Typhon goes forward: land-based sea strike remakes the Pacific

In 2025 the U.S. Army’s Typhon rolled off cargo ramps in Australia and Japan, proving that truck-mounted SM-6 and Tomahawk batteries can hunt ships from shore. Here is how mobile launchers, smarter software, and allied basing are rewriting deterrence across the Indo-Pacific.

2025: The year land-based sea strike got real

If you want to understand how the Pacific balance is shifting, picture a semi-trailer rolling off a transport aircraft in the Australian outback, raising a launch frame, and sinking a target ship hundreds of kilometers away. That scene unfolded in July 2025 during Talisman Sabre, when the U.S. Army fired a Standard Missile 6 from its Typhon Mid-Range Capability and conducted the first overseas live fire of the system. The Army’s official account called it the first Mid-Range Capability live fire outside the continental United States, and the shot validated a joint targeting chain in front of Australian counterparts and allied observers. U.S. Army reporting on the demonstration captured both the technical and political significance of the event.

By autumn 2025, Typhon had also made its debut in Japan during the Resolute Dragon exercise. The system was exhibited at Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni as part of combined drills focused on maritime and littoral defense, underscoring how forward land batteries now contribute to sea denial near key straits and island chains. Reuters detailed the arrival and the signal it sent across the region. U.S. Typhon presence in Japan. In parallel, Typhon equipment continued training and repositioning in the northern Philippines, with local troops learning how the system operates and how to move it quickly between firing sites.

These milestones confirm a simple but consequential idea. Put ship-killing weapons on trailers that can ride roads, roll onto ferries, and hop across islands, and you change how an adversary must plan. A People’s Liberation Army staff officer now has to find and fix missiles that look like freight, not just count warship launch cells at sea.

What Typhon is and why it matters

Typhon is the Army’s trailer-launched adaptation of the Navy’s strike-length vertical launch system. It fires two proven missiles:

- Standard Missile 6, a fast, multi-mission interceptor that can also strike ships and land targets at shorter ranges.

- Tomahawk Block V, a long-range cruise missile family that includes a maritime strike variant with an anti-ship seeker.

Four launchers plus a battery operations center make up a typical Typhon battery. Each launcher carries four canisterized missiles, for 16 ready rounds per battery. The launchers and the command trailer are pulled by heavy Oshkosh tractors already common in Army service. That matters because it keeps the system compatible with existing transport, maintenance, and driver training pipelines.

What Typhon does strategically is more important than the hardware. It puts the Navy’s blue-water lethality on asphalt. A weapon that used to live in a destroyer’s vertical launch cell can now live in a parking lot, disperse among warehouses, or ride a commercial ferry to a new island. That breaks the old assumption that sea-denial firepower only sails.

How the batteries move, hide, and reload

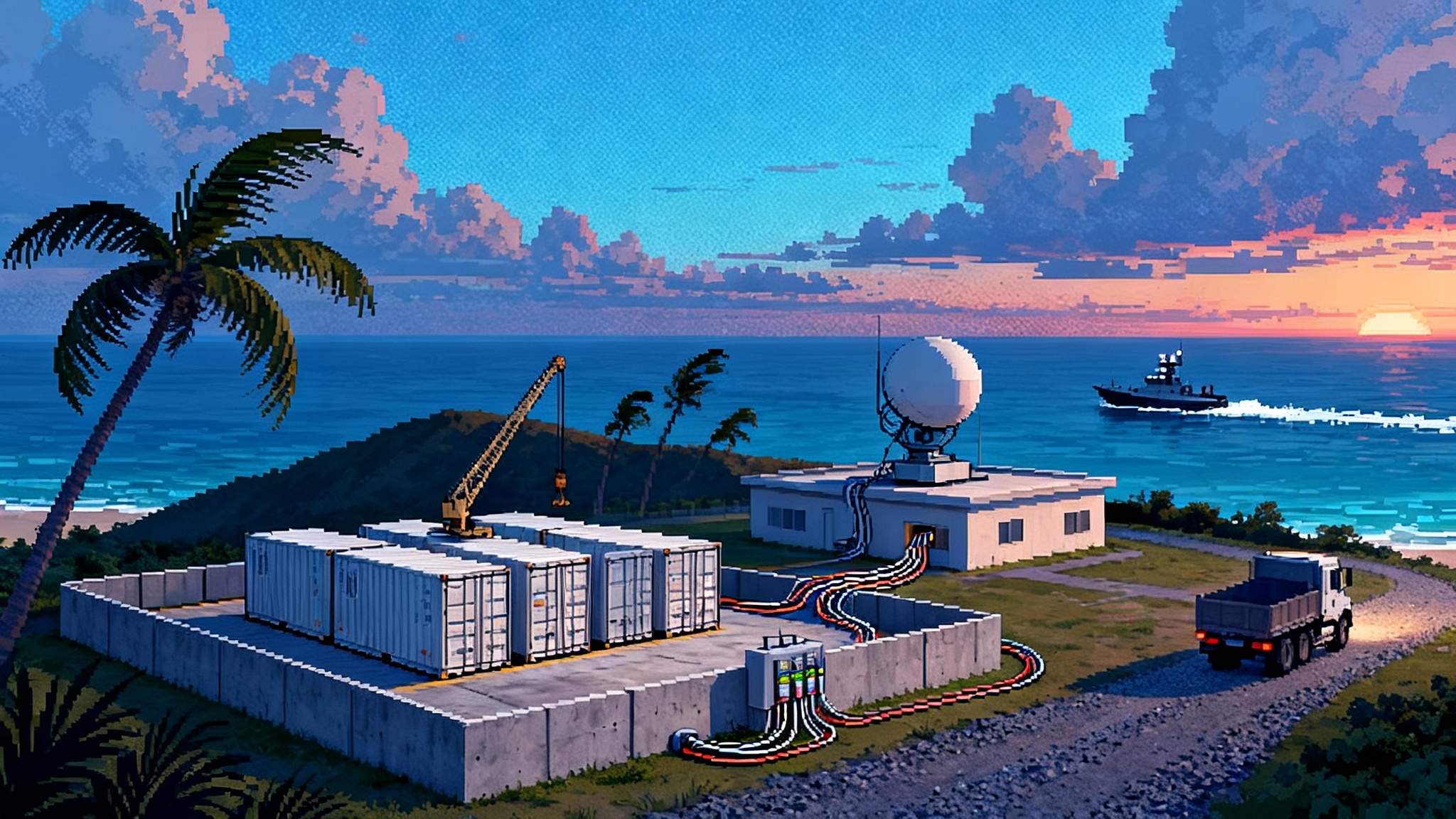

Mobility. Typhon’s components were sized from the start to fit into common global logistics. A single launcher is a 40-foot container footprint on a trailer. Crews can tow the battery along highways, secondary roads, and prepared dirt surfaces. For longer jumps, launchers can fly in a C-17 transport aircraft, then roll straight out and onto local roads. In exercises, the batteries have embarked on landing craft, trained alongside joint logistics over-the-shore units, and used pre-surveyed staging areas that let them disperse fast after unloading. For another road-mobile long-range fires example, see hypersonic road mobile fires.

Concealment. Survival starts with looking like everything else. Typhon rides on the same heavy trucks that move fuel, generators, or bridge sections. Crews practice emission control, limit radio chatter, and use preplanned firing points with multiple exit routes. Camouflage nets, thermal discipline, and decoys add clutter to the adversary’s target list. The point is not to be invisible forever. It is to remain unfindable long enough to shoot and move.

Reloading. A battery’s immediate punch is 16 missiles. Sustained combat depends on rapid reloads using canisters that slide horizontally onto the launcher racks. That approach avoids dangling heavy loads on cranes in the open for long periods, and it allows reload vehicles to swap empty for full canisters at covered sites. The canister approach also simplifies multinational logistics. A Tomahawk canister is a Tomahawk canister whether it is headed for a ship or a trailer, which lets the joint force pool stocks and send them where tempo demands.

The combination of road mobility, horizontal reload, and canister commonality is what makes Typhon a ferries and freeways system. The battery can drive aboard a roll-on roll-off vessel or a military landing craft, refuel at a coastal logistics point, and then disappear inland to wait for a cue.

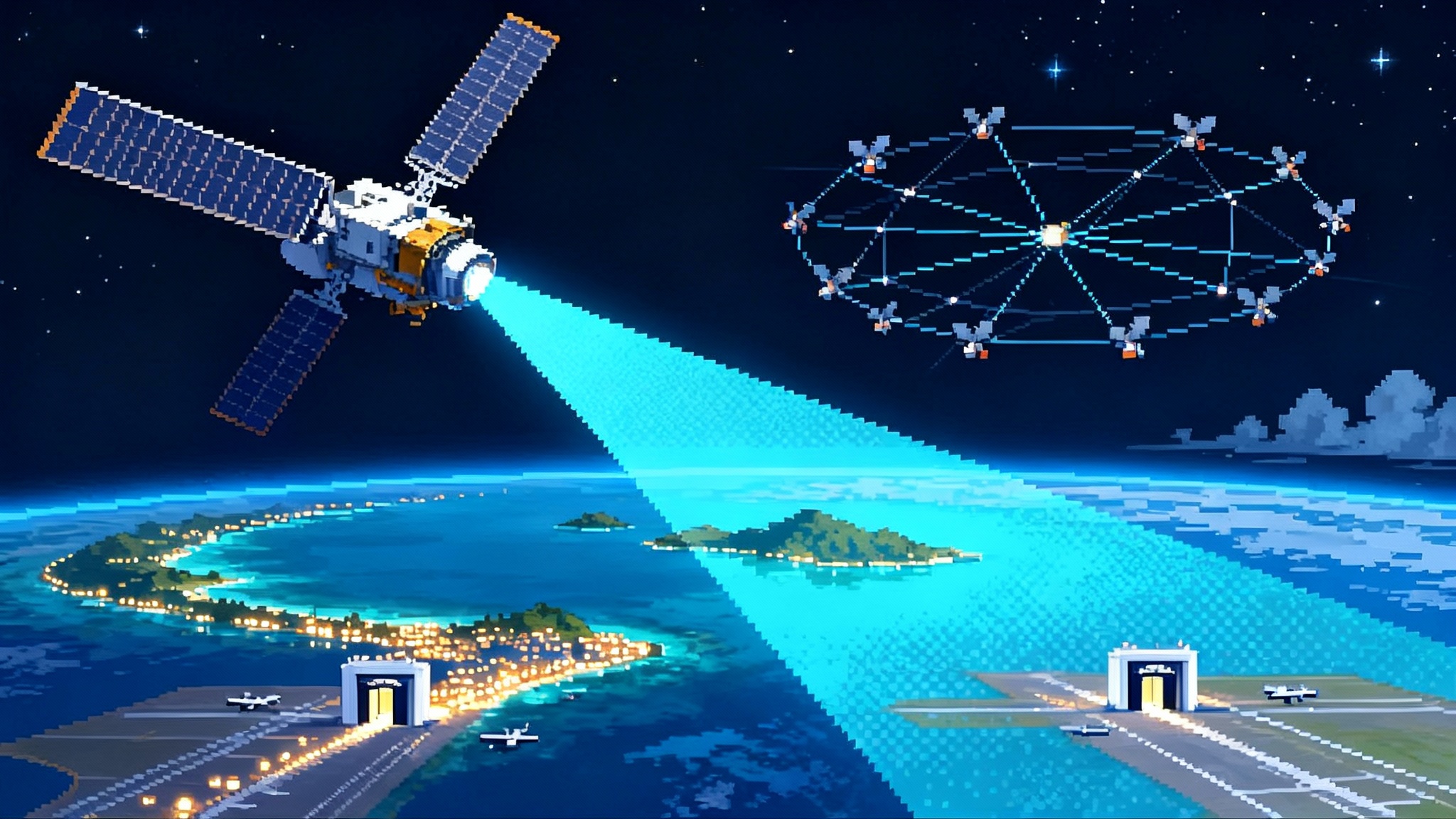

The kill chain that feeds a land shooter

Typhon is only as good as the kill chain that aims it. The Pacific kill chain is now a mesh of sensors on satellites, maritime patrol aircraft, unmanned ocean scouts, destroyers, and airborne early warning planes. The joint network that carries their tracks has been evolving toward real-time targeting and re-targeting under the Pentagon’s Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control vision, often called CJADC2. Within the Department of the Navy, Project Overmatch is the push to get sensor data to the best positioned shooter, whether that shooter is a ship, an aircraft, or an Army trailer on a coastal road. Navigation resilience will also lean on reprogrammable GPS and timing. The goal is simple. If a P-8A maritime patrol aircraft or a space-based sensor sees a target first, a Typhon battery should be able to act on that data as fast as a destroyer could.

The Talisman Sabre live fire was not just a missile shot. It was a rehearsal for that networked reality. U.S. Army, Marine Corps, and Australian Army units executed a combined fires sequence that integrated air defense coverage and maritime strike. The lesson is that the launcher is only the end of a much larger process that senses, verifies, assigns, and deconflicts fires across services.

Why land-based maritime strike changes the calculus

- It saturates the battlespace with launch points. Dozens of road turnouts, driveways, and hardstands become potential firing positions. That forces the opponent to spend sensors, time, and munitions on a much wider set of suspected launch sites.

- It multiplies allied choices. A U.S. battery at an air base can co-base alongside host nation units and plug into local protection and logistics. Co-basing creates political and operational interdependence. It also improves reload speed and security because the battery lives inside a defended ecosystem rather than in a remote camp.

- It unlocks new deception. A small convoy of white covered trailers can be real launchers, decoys, or both. That ambiguity cannot be resolved quickly at long range, especially over land clutter and civilian traffic.

Distributed launchers also pair naturally with attritable airpower; see Replicator mass in the Pacific.

For the People’s Liberation Army, this means the old math of counting American vertical launch cells at sea is incomplete. The number of land-based cells in theater can change rapidly, surge during a crisis, and hide among the thousands of trucks that move daily across island highways.

Production ramps, stockpiles, and the next missiles

Hardware availability will decide whether this concept scales. There are three parallel lines to watch.

-

Standard Missile 6. Production of the SM-6 Block IA continued in 2025 with fresh Navy orders for the interceptor that Typhon fires in a surface strike role. Program documents flagged budgeting risks that could slow the line if supplemental funding falters, yet the long-term plan still points to hundreds of rounds across the next several years, including buys tied to allied demand. A separate effort to create the SM-6 Block IB with a larger 21-inch rocket motor remains in development after a funding pause, with the motor work continuing. If Block IB enters service later in the decade, it would extend range and speed for land launch, though the exact performance envelope will remain classified.

-

Tomahawk Block V. The Navy and industry have been recertifying Block IV Tomahawks to the Block V standard while building new rounds. Recent contracts included mixed Service and allied quantities, with Japan and Australia joining the buy. The Maritime Strike Tomahawk adds a seeker and processing that allow the missile to hunt ships, while the Block Vb variant equips a new multi-effects warhead for hardened land targets. The Navy also authorized a large batch of anti-ship seeker kits to expand the pipeline through the late 2020s.

-

Launchers and battery kits. Lockheed Martin assembles Typhon launchers in the same industrial ecosystem that supports naval launch systems. An Army battery uses common prime movers and support gear, which helps field units keep the trucks rolling. The Army has two batteries already fielded, with more planned for the Multi-Domain Task Forces that align to Indo-Pacific and European theaters between 2026 and 2028.

Taken together, these steps point toward a sustainable floor of capability by the late 2020s. The most important change will be software. Every year the targeting software, the data paths, and the seekers gain features. The future looks less like a new airframe and more like new code that fuses a different radar track, recognizes a specific ship class, or rides a new path through a jammed spectrum.

Allied pathways in Japan and Australia

Japan’s role is pivotal. The Typhon appearance at Iwakuni in 2025 happened alongside the country’s own investments in long-range strike and its purchase of Tomahawk missiles for destroyers. Japanese and American officials have discussed deeper industrial cooperation on missile production and sustainment as a way to stabilize supply and speed deliveries. As joint exercises expand, a realistic near-term path is co-basing and data sharing that gives a U.S. battery Japanese protection, fuel, and local sensor access while giving Japanese commanders a new lever in littoral defense.

Australia is building a land-based maritime strike culture. The Australian Army’s 10th Brigade is organizing around long-range fires and littoral maneuver, and Talisman Sabre showed how easily a U.S. battery can mesh with Australian air defense and command nodes. Australia’s growing fleet of landing craft and its northern coastal training areas make it an ideal laboratory for how to move and hide road-mobile launchers across long distances using military and commercial lift.

The survivability and escalation tradeoffs

Typhon is not a silver bullet, and its value depends on choices that carry risks.

- Survivability vs. emissions. To be survivable, batteries must limit electronic signatures and use preplanned routes and caches. That discipline can slow the tempo of fires if commanders over-optimize for stealth. If they over-communicate, batteries become easier to geolocate and target.

- Dispersal vs. protection. Dispersal across civilian road networks makes targeting harder, but it exposes crews to threats away from hardened bases. The practical answer is a mix. Some launchers stay inside strong defenses and others move out for short windows to shoot and scoot.

- Presence vs. provocation. Parking a land-based anti-ship battery on allied soil sends a message. It can also be portrayed as escalation by an opponent. The mitigating factor is transparency and routine. The more often allies train with rotation schedules, published safety procedures, and visible coordination with local authorities, the harder it is to paint a mobile battery as a surprise weapon.

What to watch next

- More joint sensor-to-shooter events. Expect exercises that practice passing maritime targets from space and patrol aircraft directly to a land launcher without a Navy ship in the loop. The faster these chains become, the more the launcher’s location matters less than the quality of the network.

- SM-6 Block IB milestones. The 21-inch motor work is the long pole. If the Navy restarts full funding and flight tests proceed, the Army will have a higher performance option to integrate on Typhon in the second half of the decade.

- Tomahawk seeker and software updates. Maritime Strike Tomahawk upgrades, including passive sensing and new processing, will quietly make each round smarter. Software-centric improvements will define the missile’s next leap more than airframe changes will.

- Allied integration. Look for Japan to expand combined drills that place land launchers in coastal defense scenarios, and for Australia to refine its littoral logistics around hiding batteries in the north. The Philippines, which already trains on Typhon procedures, will likely develop site packages that streamline how a battery comes and goes without friction.

The forecast: by 2026 to 2028, a default deterrent layer

A clear pattern is taking shape. By the time the Army fields additional Typhon batteries to its Multi-Domain Task Forces and allied infrastructure matures, distributed coastal strike will be a default layer running from northern Australia through the Philippines and Japan. Not every island will host a battery at all times. What will be present all the time is the uncertainty that a battery can appear quickly, stay long enough to matter, and then vanish back into the flow of trucks and ferries.

Deterrence in the Indo-Pacific will rely less on a small number of exquisite platforms and more on a web of good enough launch points connected by better software. Typhon is the rough and ready embodiment of that shift. It turns maritime firepower into something you can tow, reload behind a warehouse, and quietly move at night. Warships will still matter. Submarines will still matter. What changes is that every adversary ship sailing within range of a coastal road network now has to wonder whether the next bend in that road hides a battery that can reach it.

That is the kind of doubt a defender wants to plant. In 2025 Typhon proved it can do so in practice, not just in PowerPoint. The next three years will decide how widely that doubt spreads, and whether the network behind it becomes fast and resilient enough to make land-based sea strike a permanent feature of Indo-Pacific deterrence.