Lean Loss, Stronger Bodies: Myostatin Blockers with GLP-1s

Phase 2 data from June 2025 show apitegromab with tirzepatide preserved about 55 percent of lean mass and added 4.2 pounds of muscle versus GLP-1 alone. An FDA manufacturing setback in September 2025 did not question efficacy, and next‑gen agents are close behind.

The breakthrough that reframes weight loss

For years, the promise of powerful glucagon-like peptide 1 therapies has come with a catch. Yes, semaglutide and tirzepatide can drive double-digit weight loss, but a sizable portion of the scale drop comes from muscle. In June 2025, that story changed. Scholar Rock reported Phase 2 results from EMBRAZE showing that apitegromab, a selective myostatin-blocking antibody, preserved roughly 55 percent of the lean mass that would otherwise be lost during tirzepatide-induced weight loss. That translated to an extra 4.2 pounds of muscle versus tirzepatide alone over 24 weeks, with statistical significance. The company framed it as better quality weight loss, and the numbers back that up, with participants on the combination losing a higher share of fat and a lower share of muscle. You can read the June 18, 2025 topline data in Scholar Rock’s release under June 2025 EMBRAZE results.

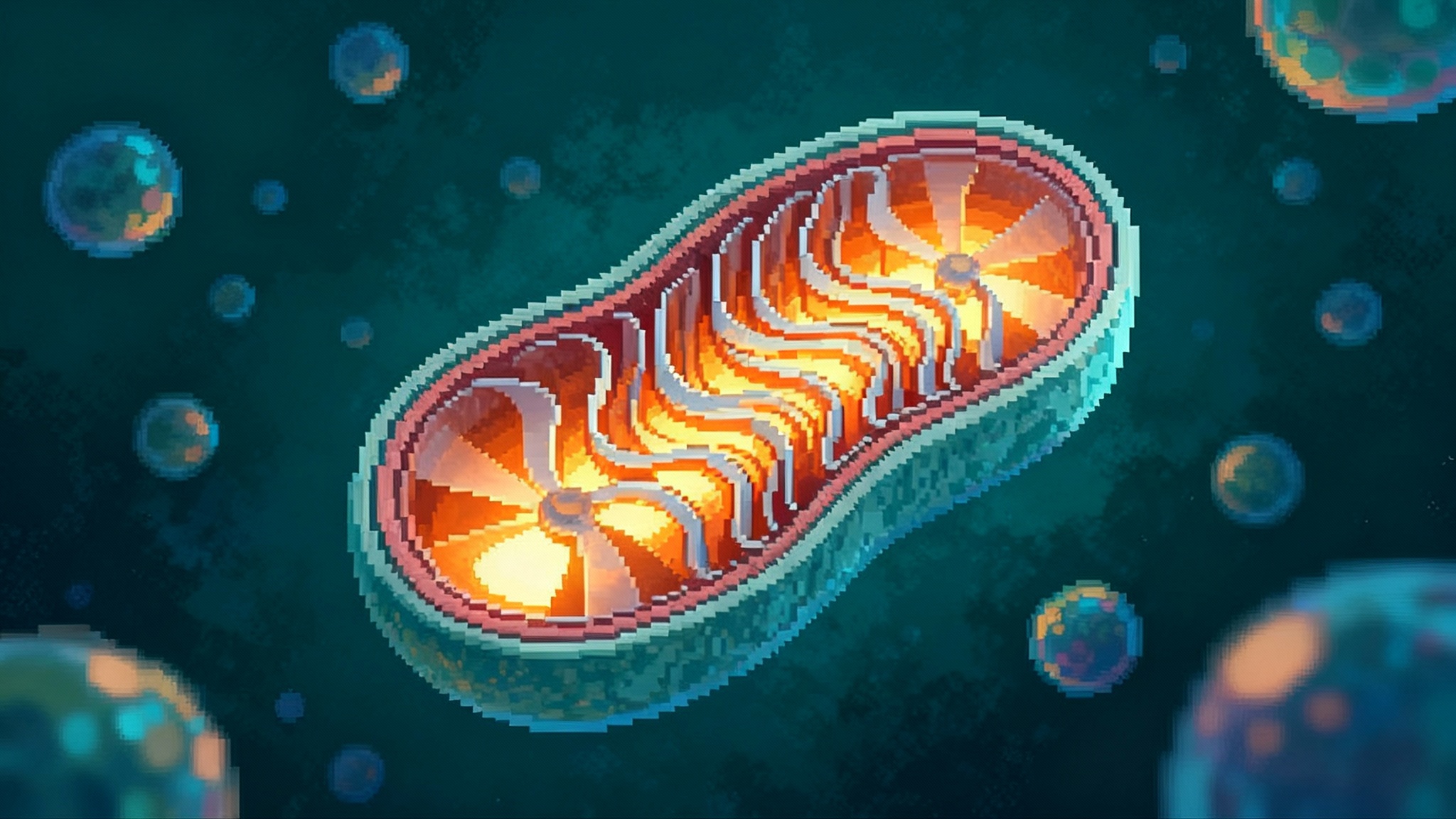

This is not a cosmetic tweak. Muscle is the body’s engine and shock absorber. It burns calories at rest, stabilizes blood sugar after meals, supports joints, and buffers falls. When weight loss shaves away both fat and muscle, patients may meet a target on the scale yet end up with lower basal metabolic rate, worse strength, and a higher risk of regain. Preserving muscle during weight loss is like protecting the payroll during a budget cut. You still cut spending, but you do not fire the people who make the place run.

Why muscle loss has been the tax on rapid weight loss

Rapid weight loss changes the body’s accounting. Calorie intake falls, the body uses stored fuel, and the easiest fuel to tap is not only fat but also amino acids from muscle. Even with adequate protein, people on potent appetite-suppressing therapies tend to move less, train less intensely, and lose some lean mass. In studies with glucagon-like peptide 1 therapies alone, roughly a quarter to a third of total weight loss has often come from lean mass. That is a large tax to pay. The EMBRAZE data suggest apitegromab can cut that tax by more than half while keeping the fat loss that patients and clinicians want.

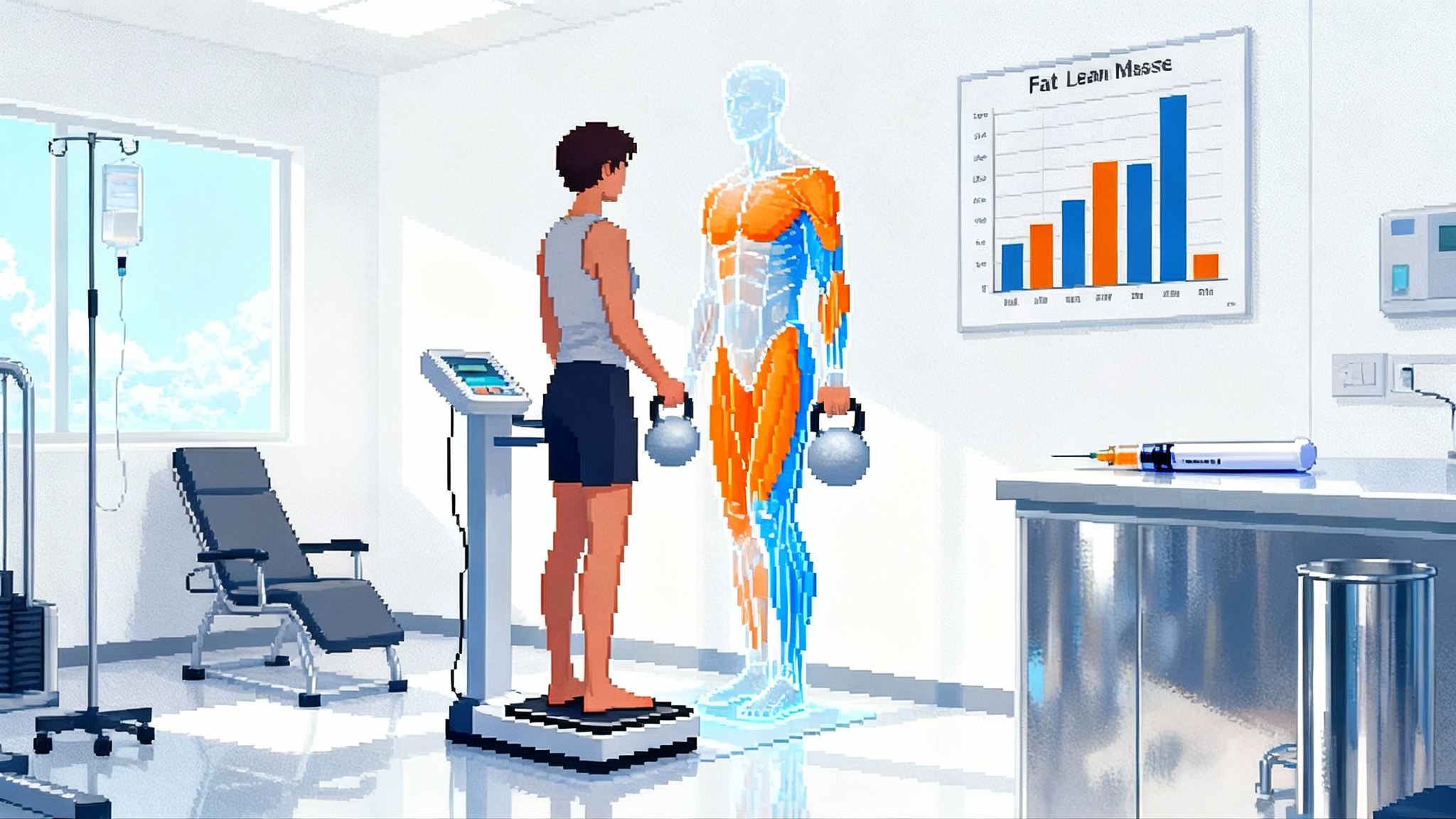

The Phase 2 specifics matter. Over 24 weeks, participants on tirzepatide alone lost about 13 percent of body weight, and 30 percent of that loss was lean mass. The apitegromab plus tirzepatide group lost about 12 percent of body weight, and only about 15 percent of that was lean mass. Fat mass loss remained strong in both arms, roughly 18 to 19 pounds in the combination group versus about 18 pounds in tirzepatide alone. The absolute difference in lean mass retention was 4.2 pounds in favor of the combination. Taken together, the combination yielded a higher quality body composition shift for nearly the same total weight loss.

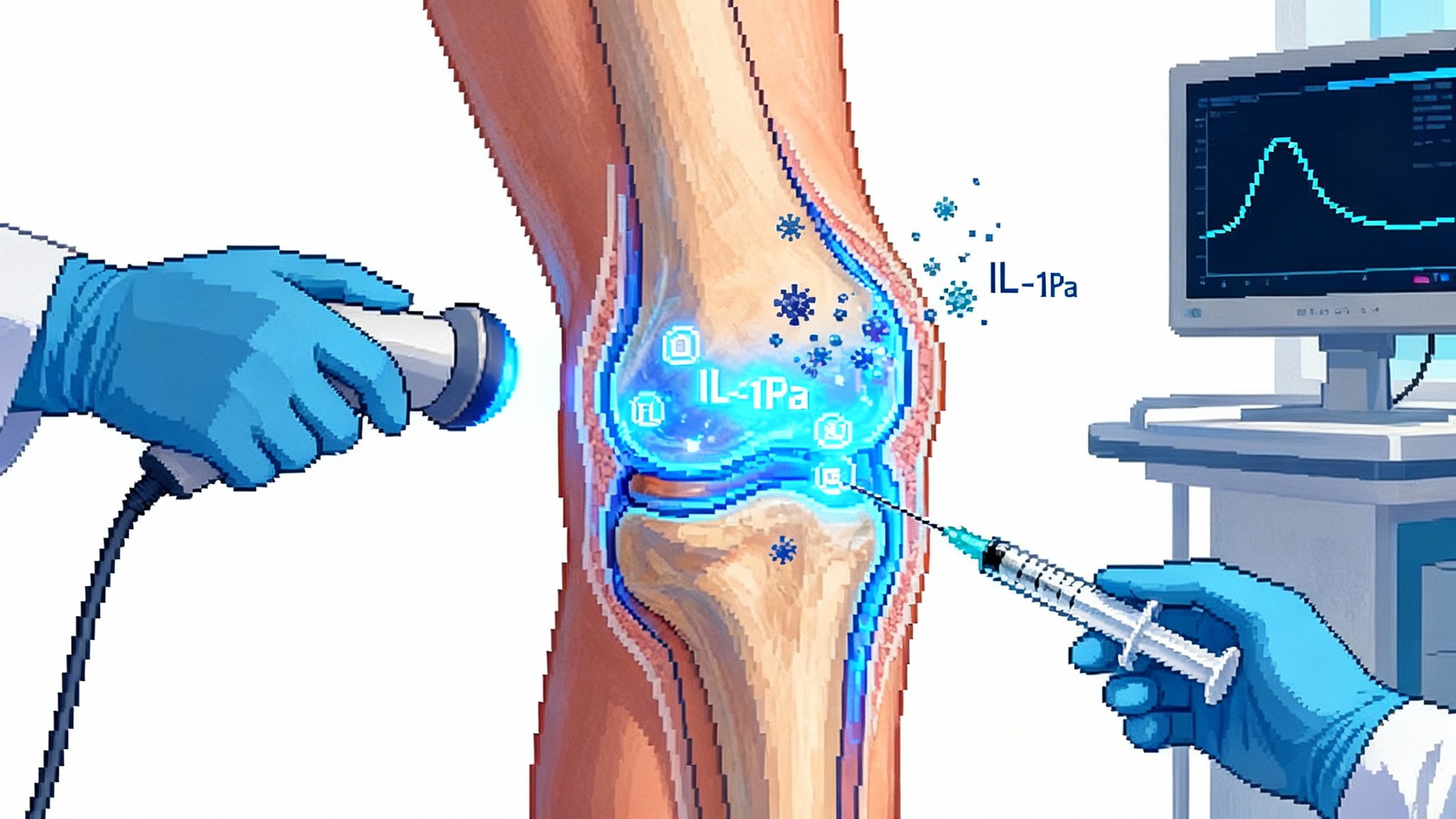

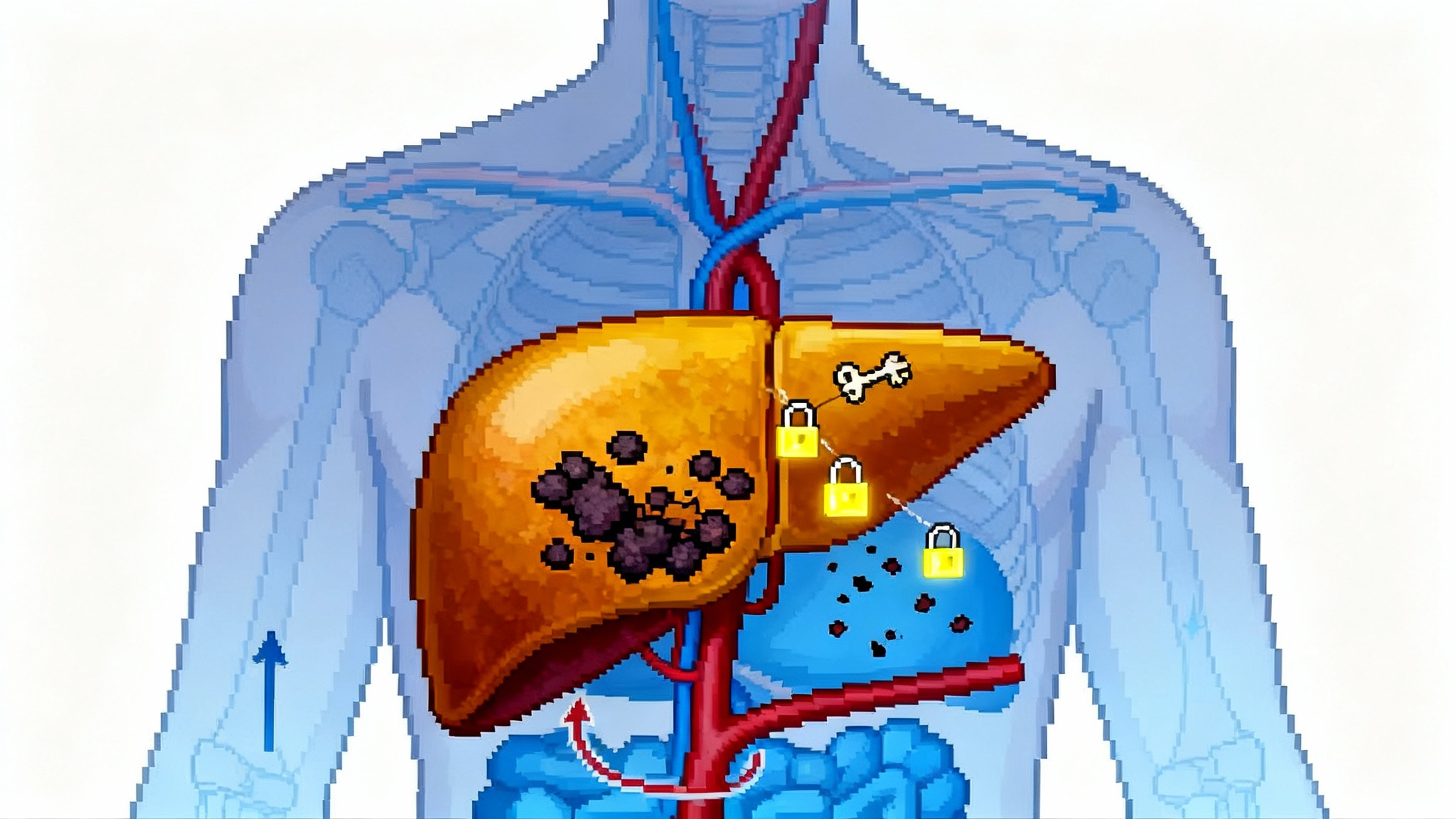

A simple map of the biology

Myostatin is a molecular brake on muscle growth. When myostatin binds its receptor on muscle cells, it tells the tissue to hold back on building new fibers. Evolution likely used that brake to keep bodies from wasting calories when food was scarce. A myostatin blocker lifts that brake. The nuance here is selectivity. Myostatin is part of the transforming growth factor beta family, which includes close cousins like growth differentiation factor 11 and activin A. Blocking those would have unwanted side effects outside muscle. Scholar Rock’s antibodies target the pro and latent forms of myostatin before it fully activates, with high selectivity intended to spare those relatives. In concept, that lets clinicians dial down weight while dialed-up muscle building capacity stands by to preserve strength and metabolic rate.

Think of the stack as a one-two punch. Tirzepatide reduces appetite and improves insulin and glucagon signaling, so patients eat less and burn stored fuel. Apitegromab reduces the penalty on muscle while the calorie deficit does its work. The result is a higher proportion of weight lost as fat rather than as muscle.

What the numbers mean for patients and clinicians

The composite takeaway is simple. On glucagon-like peptide 1 therapy, the body tends to lose about 70 percent fat and 30 percent lean mass. With a myostatin blocker on board, EMBRAZE suggests about 85 percent fat and 15 percent lean mass. If a patient loses 30 pounds, that could be the difference between 21 pounds of fat and 9 pounds of lean mass versus 25.5 pounds of fat and 4.5 pounds of lean mass. That second profile is more metabolically favorable, more functional for daily life, and may make maintenance easier after the active weight loss phase ends.

A small reduction in total weight loss was observed in the combination group, about a percentage point less on the scale over 24 weeks. That is unsurprising. Keeping muscle on the chassis can slightly blunt the total number shown on the scale, but the health utility is higher. Endurance coaches see a similar effect when athletes add resistance training during a cut. The scale may slide a little slower, yet performance improves.

Safety is always the first question. EMBRAZE reported that apitegromab was generally well tolerated and that the safety profile looked consistent with prior studies. The trial used 10 milligrams per kilogram by intravenous infusion every four weeks. The schedule leaves room for optimization, including future subcutaneous approaches if next-generation agents prove suitable. For now, the finding that matters most is feasibility. Patients can take a myostatin blocker with a glucagon-like peptide 1 therapy and do well over six months while keeping more muscle.

The regulatory wrinkle, and why it matters less than it sounds

In September 2025 the United States Food and Drug Administration issued a complete response letter declining to approve apitegromab for spinal muscular atrophy on the first pass. Crucially, the letter cited observations at a third-party fill-finish facility in Indiana, not any issues with apitegromab’s efficacy or safety. Scholar Rock said it planned to resubmit the application once those plant observations were resolved. The company’s statement appears under September 23, 2025 FDA letter.

For obesity and cardiometabolic use, that manufacturing delay is news only insofar as it affects near-term supply and timelines. It does not undercut the pharmacology or the clinical logic of muscle preservation during weight loss. The larger point is that myostatin inhibition is now a workable co-therapy concept, with human data that show a clear body composition benefit alongside a modern weight loss drug.

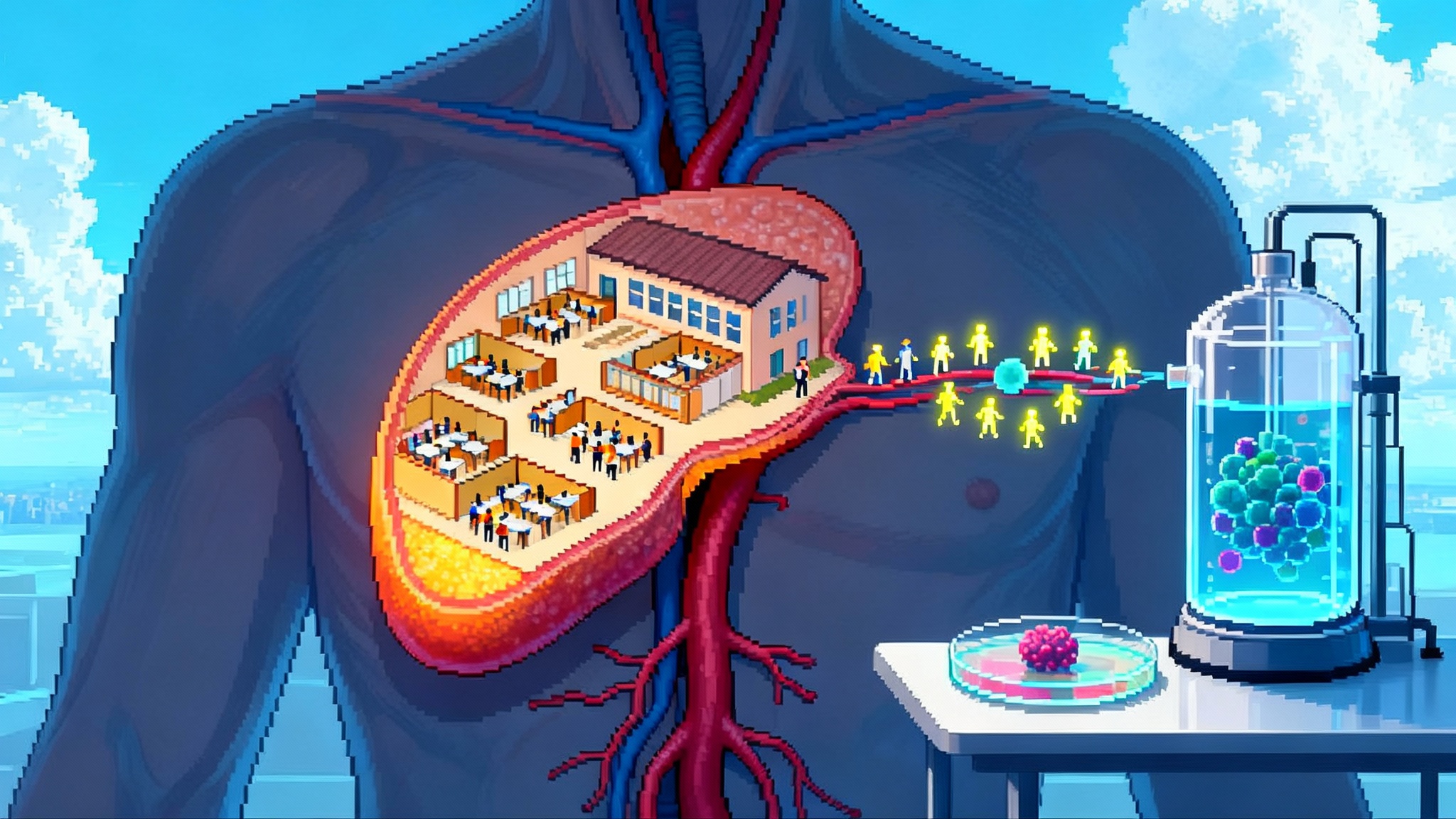

A real market is coalescing around sarcoprotection

The field is moving fast. Several companies are testing muscle-sparing approaches in combination with weight loss drugs. Eli Lilly has tested bimagrumab, a myostatin pathway agent first explored at Novartis, in metabolic settings. Regeneron has a myostatin blocker program, and others are exploring either antibodies or genetic and RNA approaches to modulate the pathway. Some developers are taking a different angle with selective androgen receptor modulators to increase muscle in parallel with weight loss. The signal across programs is the same. Health systems and patients are starting to ask not only how much weight can be lost, but what kind of weight it is.

Why does this matter for healthspan? Maintaining muscle helps preserve mobility and independence. It supports glucose disposal after meals. It stabilizes gait and reduces falls. It also likely helps with weight maintenance after the active phase of therapy, because muscle raises the calories you burn at rest and makes physical activity feel easier. For older adults and those with chronic conditions, keeping muscle while losing fat is not a nice to have. It is the difference between frailty and resilience. This thinking aligns with the broader healthspan playbook, including the 2025 cellular energy shift.

What to do differently now

-

Clinicians should measure body composition, not just weight. Use dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry or bioimpedance where available. Track lean mass, not just body mass index. If you cannot get a scan, track grip strength, chair stands, and gait speed as practical proxies.

-

Design programs that pair pharmacology with resistance training and protein targets. A myostatin blocker will not replace the need to load muscle. It makes the training signal more valuable by taking the brake off. Aim for at least two sessions per week that include compound lifts or bodyweight movements, and set a daily protein target aligned with lean body weight.

-

For patients on glucagon-like peptide 1 therapy who feel weaker or plateau on the scale, discuss body composition testing. If a muscle-preserving co-therapy becomes accessible in your care setting, consider it for those at higher risk of sarcopenia, such as adults over 60, individuals with low baseline grip strength, and anyone with a history of falls.

-

For payers and employers, refine coverage criteria to reward quality of weight loss. If a combination yields equal or better fat loss with less muscle loss, the downstream savings in falls, fractures, and functional decline can outweigh slightly higher drug costs. Pilot programs can compare claims for physical therapy, orthopedic procedures, and sick days between combination and monotherapy cohorts. This mirrors how payers are approaching novel prevention plays like one-dose siRNA resets heart aging.

-

For trial designers and regulators, include functional endpoints. Body composition is a start, but what patients feel and do matters too. Add gait speed, chair rise time, six-minute walk, and patient-reported fatigue to the list of secondary endpoints. These are sensitive, clinically meaningful, and easy to standardize.

Where the science goes next

The next phase will test whether muscle preservation drives better long-term outcomes. The most important questions now are not about DEXA values alone. They are about the slope of weight regain after drug taper, injury risk, glucose control, and physical function twelve to twenty-four months later. If the combination reduces the yo-yo effect that many people experience after stopping glucagon-like peptide 1 therapy, that would be a major win for health systems.

Dosing and delivery will also evolve. The current apitegromab schedule is intravenous every four weeks. That works in a controlled trial, yet many patients would prefer infrequent subcutaneous dosing that fits alongside their weekly or biweekly weight loss therapy. Pipeline candidates are being optimized for that kind of delivery in cardiometabolic care. Scholar Rock’s own next-generation agent, SRK-439, is positioned for obesity and related cardiometabolic disorders, with design choices that aim to combine selectivity, durability, and practical dosing. As new agents arrive, expect a focus on formulation, the ability to combine with other common drugs like metformin or sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, and on safety over multi-year use.

Safety surveillance will need to be proactive. Increasing muscle mass sounds unambiguously good, but clinicians should watch for rare connective tissue complaints, unusual muscle cramps, or changes in tendon load tolerance as patients ramp up activity with new energy. The early safety picture looks encouraging, and the pathway biology supports muscle-specific effects, yet surveillance builds trust.

The business end of better weight loss

If muscle-preserving stacks become standard of care, two things change at the system level. First, mobility and independence stay higher for longer in aging populations. That is the core of healthspan. Second, health economics improve. Fewer falls and fractures, less frailty, better glucose control, and faster rehabilitation after routine procedures will save money. Payers will want head-to-head evidence with endpoints they can price, like fracture rates or physical therapy visits avoided. Those studies should start now, in parallel with larger Phase 3 body composition trials, and learn from adjacent aging trials such as our plasma exchange aging trial.

There is also a strategic signal in the September 2025 Food and Drug Administration letter. A complete response letter for a manufacturing site issue shows how nonclinical factors can shake timelines without changing clinical logic. It is a reminder to diversify supply chains and to build redundancy for fill-finish steps that the sponsor does not control. For the obesity use case, this lesson means the difference between a nice idea and a scalable, reliable product line.

What to watch in 2026

-

Larger and longer trials of myostatin blockers with glucagon-like peptide 1 therapies, ideally with one year follow up after dose reduction or withdrawal.

-

Subcutaneous or longer-interval formulations that make the combination practical in primary care rather than only in specialty clinics.

-

Trials that include older adults and those with sarcopenia at baseline, since these are the people who will benefit the most.

-

Combinations beyond glucagon-like peptide 1 therapy, such as pairing with insulin sensitizers or with supervised resistance training programs delivered through digital physical therapy.

-

Real world evidence programs that pull electronic health record data on strength, mobility, and injury to complement imaging.

The bottom line

EMBRAZE gives us the first clear human proof that we can stack weight loss efficacy with muscle preservation in a way that lines up with healthspan. It is an engineering upgrade to the weight loss journey. Instead of trading away strength for a smaller number on the scale, patients can lose fat while holding on to the muscle they need for life. The regulatory bump in September 2025 was about a contractor’s plant, not about the science. The science points to a near future where sarcoprotection sits beside appetite control as a standard part of care. If you work in this field, begin to measure what matters, design programs that protect the engine, and plan for a world where weight loss is not only faster, but also smarter.