Sea-Based Hypersonics Hit the Fleet: CPS on Zumwalt, Virginia

After a successful end-to-end flight in May 2025, the Navy’s Conventional Prompt Strike is leaving the test range for real ships. Here is what CPS on Zumwalt and Virginia means for deterrence, timelines, and Indo-Pacific operations.

From test range to warship

On May 2, 2025, the Navy moved its Conventional Prompt Strike program from promise to proof with a successful end-to-end flight test that used the same cold-gas launch approach planned for fleet platforms. The event mattered because it stitched together the full kill chain in one shot, from canister ejection to boost and glide, validating the architecture the service intends to field at sea. The Navy did not share range figures, but it did say the test demonstrated the integrated All-Up-Round that the Army and Navy are developing in common. In short, the technology is no longer a lab curiosity, and the Navy’s sea-based path is real enough to plan around. Navy confirms end-to-end test.

For surface forces, 2025 is also the year when modification work on the Zumwalt class matured from drawings to shipfitting and systems delivery. For the submarine force, the program is aligning the missile and canister with the Virginia-class payload architecture, even as the industrial base wrestles with throughput and labor.

What CPS is, and why cold launch at sea matters

CPS is a boost-glide conventional weapon. A large two-stage booster pushes a maneuvering glide body to hypersonic speeds and high altitudes, then the unpowered body rides a tailored profile to its target. Two aspects matter for naval use:

- Cold-gas ejection: the weapon is pushed clear of the ship or submarine before the booster lights. That reduces deck wake heating risk, eases integration with existing launcher envelopes, and allows commonality across surface and subsurface canisters.

- Common All-Up-Round: a shared Army Navy round simplifies production and keeps test data flowing between services. It also means the Navy’s at-sea integration benefits from the Army’s shore-based test cadence.

The result is a conventional weapon that can hit time-sensitive, well-defended targets at ranges where Tomahawk timelines begin to look long. The glide body will not advertise its approach with the predictable route of a ballistic arc, and it will not linger in the way a subsonic cruise missile does. That is the core of CPS’s deterrent value.

For how resilient sensor networks feed kill chains under threat, see the related discussion of the SDA Tranche 1 satellite mesh.

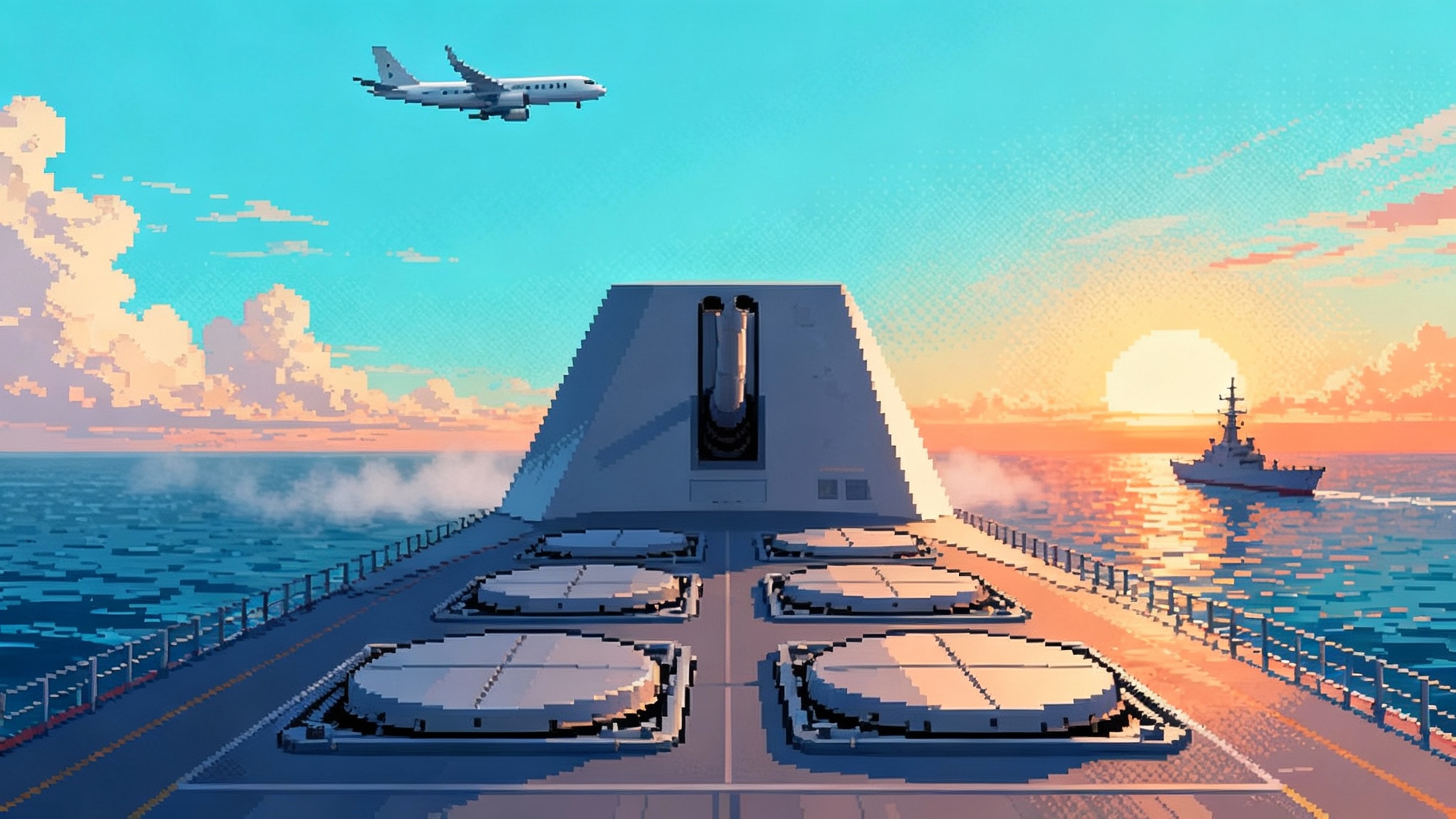

DDG-1000 load-outs and CONOPS

The hardware is as important as the missile. On Zumwalt-class destroyers, the two 155 mm Advanced Gun Systems are being replaced by four large-diameter launchers sized for CPS. The Navy’s current design fits four Multiple All-Up Round Canisters, each holding three CPS rounds, for a total of twelve hypersonic missiles. Those tubes are the 87 inch class, purpose built for the round and paired with the ship’s upgraded fire control and power distribution. The total battery is modest in count but strategic in effect. Four MACs, 12 CPS rounds.

A practical DDG 1000 concept of operations looks like this:

- Outer ring strike: operate in the Philippine Sea, Western Pacific high seas, or North Pacific approaches. Use the ship’s low-observable shaping and emissions control to complicate targeting, but treat the hull as a magazine ship first.

- Cueing and kill chain: receive aimpoints from joint space and airborne ISR, P-8A and MQ-4C patterns, and undersea sensors. CPS requires accurate coordinates at launch; the battle is won by the quality and freshness of the target.

- Mixed battery: retain Standard Missiles and Tomahawk in the Mk 57 PVLS for self-defense and secondary strike. Use CPS for first salvo shots against hardened C2, coastal anti-ship ballistic missile brigades, and critical SAM nodes that enable the adversary’s anti-access envelope.

- Valves not floods: twelve shots are precious. Fire in pairs against highest priority time-sensitive targets, posture for rapid re-attack only when ISR confirms effect, and hold back a ready reserve to exploit new targets of opportunity.

In practice, a CPS-equipped Zumwalt does not sprint into the first island chain to trade blows. It stands off, preserves survivability, and makes the rest of the force more lethal by collapsing enemy air defense and long-range fires.

The path to Virginia-class integration

The submarine variant of CPS rides in large-diameter tubes tied to the Virginia Payload Module on Block V and later boats, and to backfit options as they mature. The design intent is compatibility between the surface launcher and the submarine canister, leveraging the same All-Up-Round and much of the same launch control software. The Navy has been clear that the timeline for undersea integration trails surface by several years. Between inserting a new round into the VPM, qualifying new handling gear, and ensuring crew training and weapons safety for a very large solid-rocket booster, early 2030s is the realistic mark for operational deployment on Virginias.

Three factors drive that schedule:

- Industrial throughput: the Virginia program is working back toward two boats per year, while also supporting AUKUS demands and recovering from supplier shortfalls. Hypersonic integration rides on that recovery curve.

- Test sequencing: the Navy needs a stable at-sea test cadence that exercises the submarine launcher, canister, and weapon together. That means more end-to-end events and instrumented shots after surface integration proves out.

- Software and safety: the ship control systems, combat system interfaces, and weapons handling rules for CPS differ from Tomahawk. The Navy must qualify those differences carefully to keep the boats safe.

Once on Virginias, CPS will give the fleet a covert, survivable hypersonic option that can complicate adversary targeting across the entire Indo-Pacific, from the Philippine Sea to the Northern Arabian Sea.

Deterrence and strike timelines in the Indo-Pacific

Deterrence rests on the adversary’s belief that key assets can be held at risk at speed. CPS shortens the time from commitment to effect. Instead of a mission planning timeline that ends with hours of cruise flight, a hypersonic shot compresses the window to tens of minutes across theater distances. That is decisive for:

- Mobile missile forces that move on a cycle measured in dozens of minutes.

- Hardened fixed sites that are only vulnerable during specific operating periods.

- High-value ships whose routes can be predicted but not guaranteed.

The psychological effect matters too. A fleet with credible sea-based hypersonics can threaten deep inland C2 hubs without forward-basing land missiles or risking manned aircraft. That dislocates an adversary’s force posture and forces them to spend resources on defense and dispersal. For a view of regional missile-defense shifts, see Guam's joint missile shield.

What changes on the adversary side

No capability moves uncontested. Expect all of the following as CPS becomes operational:

- A2/AD hardening: more decoys and camouflage for TELs, rapid displacement drills for coastal ASBM brigades, and rapid runway repair kits pre-positioned at key fields. Expect redundancies in C2 nodes and more use of fiber and buried comms.

- Hypersonic defense: theater air and missile defense will refocus on multi-phenomenology tracking. That means low-latency space sensors feeding wide-area cueing, X-band fire control radars sized for glide body tracking, and new endo-atmospheric interceptors optimized for high heating and maneuvering targets. The most effective defense will be layered and distributed, and it will be expensive.

- ASW pressure: Virginia-class boats that can carry CPS will be hunted harder. Expect more fixed seabed arrays near chokepoints, more quiet diesel-electric patrols in narrow seas, and more active sonar in barrier formations.

- Counter-ISR: CPS depends on fresh, accurate target data. Jamming of P-8A links, harassment of high-altitude ISR aircraft, cyber pressure on space-ground data paths, and kinetic counterspace risks will all rise.

In other words, CPS takes aim at the brains and long-range arms of an adversary. The response will be to move the brains, multiply the arms, and blind the sensors that feed your aimpoints. For a deeper dive on peer hypersonic trends, see China's hypersonic A2AD edge.

Industrial base and schedule risk to watch

Sea-based hypersonics stretch parts of the U.S. missile enterprise that have been under strain for years.

- Large solid rocket motors: CPS boosters are in the class that relies on a small number of qualified suppliers. Any quality escape or facility disruption drives long slips.

- Thermal protection and structures: glide body heat shields and aeroshells demand precise manufacturing and inspection processes. Yield rates will be watched closely as production scales.

- Canisters and launchers: the 87 inch launcher family is new for surface ships and must be built out in numbers for two Zumwalts in the near term and later for the submarine fleet. Volume and dimensional control in these large cylindrical structures are non-trivial.

- Test cadence: hypersonic test ranges are a shared resource. The program needs range access and instrumentation to sustain learning without long pauses.

- Workforce: shipyards and missile houses need cleared, skilled labor. Competing programs, from SSBNs to space launch, fish in the same talent pool.

The Navy has tried to buy down some of this risk by funding long lead items earlier, aligning Army and Navy test events, and pushing commonality across services. The most credible near-term milestone is completion of launcher installation and shipboard integration on the lead Zumwalt, followed by at-sea validation shots. Production learning will follow those shots.

How CPS reshapes maritime strike concepts

With CPS aboard, the surface and submarine force can orchestrate a different first day of conflict in the Western Pacific.

- Preemptive paralysis: a CPS salvo can be timed to arrive just before a larger air and missile campaign, degrading the sensors and C2 needed to defend against follow-on strikes.

- Dynamic maritime targeting: a submarine or low-observable surface combatant can take a CPS shot from outside the adversary’s main ASBM arcs, hitting ships that rely on shore-based ISR and long-range fires. The payoff is switching the burden of movement back onto the adversary.

- Distributed Maritime Operations synergy: CPS gives distant nodes in a distributed force real punch, which means fewer high-end units need to press inside the most dangerous waters early.

- Coalition interoperability: while the weapon itself is U.S. only, the kill chain that feeds it can share sensor inputs and effects assessments with allies. That tightens combined targeting cycles.

The limiting factor will not be how many missiles a single ship carries. It will be how quickly the joint force can find, fix, and finish targets that merit a hypersonic shot, then generate fresh aimpoints for re-attack without burning precious rounds on decoys or stale data.

The 2025 picture, and what to watch next

Two things happened this year that change the conversation. First, the spring end-to-end flight proved the Navy’s sea-based launch approach with the common round. Second, the Zumwalt backfit crossed visible thresholds, from gun removal to delivery of large launch system hardware and associated integration packages. Put together, CPS is now a fleet program with ships in modification, not just a test article.

What to watch over the next 18 months:

- Completion of launcher installation and shipboard integration on the lead Zumwalt, followed by a controlled schedule of at-sea trials.

- Additional end-to-end flight tests that emphasize reliability, accuracy, and canister handling fidelity across environmental conditions.

- Submarine integration milestones, especially canister qualification with the Virginia Payload Module and shore-based handling and safety certifications.

- Industrial base investment tied to large solid rocket motor capacity and thermal protection manufacturing yield.

- Tactics development for mixed batteries, including how many CPS rounds a surface action group needs to carry to sustain credible deterrence across a deployment.

Bottom line

Sea-based hypersonics are moving from press releases to hull numbers. With CPS on the way to Zumwalt-class destroyers and aligned to the Virginia-class path, the Navy is building a conventional strike option that compresses timelines, stretches enemy defenses, and makes dispersed U.S. forces more lethal across the Indo-Pacific. The technology is hard and the industrial base is tight, but the payoff is a fleet that can hold critical targets at risk fast, from outside the most dangerous waters, and without escalating to nuclear weapons. That is a meaningful shift in deterrence and in day one warfighting calculus.