USAF’s robot wingmen fly: Anduril’s test and what changes next

Anduril’s jet-powered Collaborative Combat Aircraft flew on October 31, 2025, moving the U.S. Air Force from concept slides to flight tests. Here is what changes now, from 2026-27 buys to autonomy safety cases, Pacific tactics, payload choices, and cost.

The week the concept took off

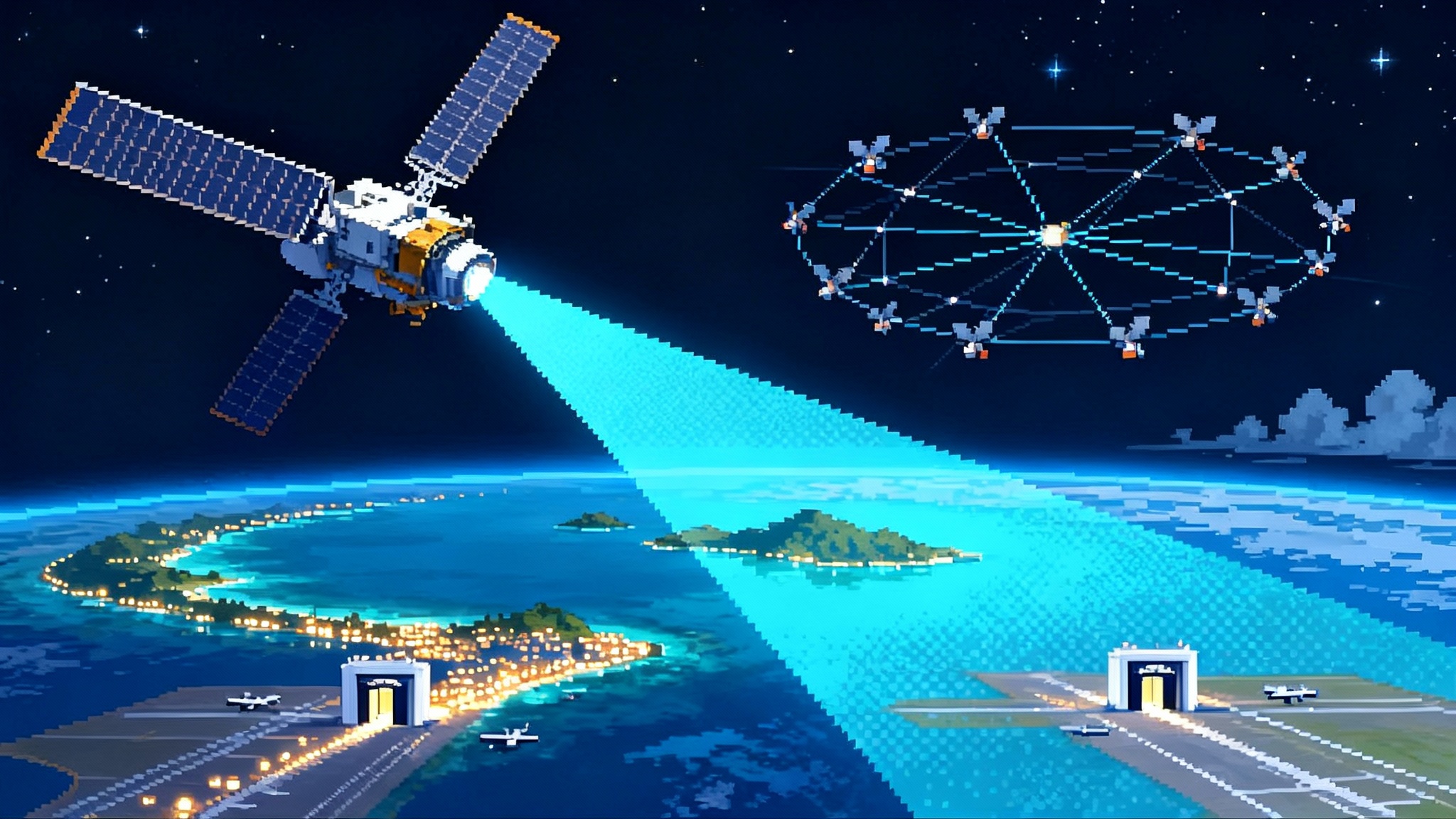

The U.S. Air Force’s plan to add uncrewed, combat-ready wingmen crossed a bright line on October 31, 2025. On that date, Anduril’s jet-powered YFQ-44A made its maiden flight in California, the second prototype in the program to reach the air and a clear signal that Collaborative Combat Aircraft, or CCA, has moved from briefing charts to runway reality. Anduril YFQ-44A first flight.

General Atomics Aeronautical Systems had already begun flight testing its counterpart, the YFQ-42A, earlier in the year. With two different prototypes flying, the service can now collect real data on autonomy behaviors, control links in heavy jamming, sensor fusion in cluttered environments, and the human factors of managing multiple uncrewed teammates from a cockpit that is already saturated with information.

It is easy to overuse the phrase turning point. Here it fits. For several years, CCA has been a promise: an affordable way to add mass, reach, and persistence to a fighter force that has been shrinking in numbers even as its missions expand across the Pacific and into concepts like land-based sea strike remakes the Pacific. This fall, the program shifted into a test campaign that can validate those promises or reveal the tradeoffs that will shape the next two years of decisions.

From PowerPoint to flightline

Two working, jet-powered prototypes mean the service can answer questions that paper studies could not. How quickly can a pilot trust autonomy that flies next to them at formation distance, and then sends a weapon where that pilot points? What happens when a datalink drops during a tight turn at the merge, or when an adversary lights up the ether with deception and noise? How do you design a display that lets a pilot supervise three aircraft without tunnel vision?

Flight tests will help sort the answers. The near-term aim is not to prove science fiction. It is to demonstrate reliable, bounded behaviors that grow mission by mission. Think of autonomy here like a careful new driver that has practiced a route dozens of times. At first it stays on a well-marked road. As confidence grows, you add night driving, then rain, then a detour. The CCA autonomy stack will similarly gain authority as it logs safe performance across more conditions and adds more skills.

Speed run to 2026 and 2027

The political and program clock is aggressive. Air Force leaders say they intend to make a competitive production decision for Increment 1 in fiscal year 2026, which begins on October 1, 2025, and then field capability before the end of the decade. That schedule was laid down when the department exercised options with Anduril and General Atomics in April 2024, and it remains the backbone of the plan. The department stated that it is on track for that decision and that a broad vendor pool stays eligible to compete for production. See the department’s statement on the competitive production decision in fiscal 2026.

What does that mean over the next 18 to 24 months? Expect a fast spiral of envelope expansion, autonomy build-ups, and early operational assessments. Do not be surprised if the service buys a small batch of airframes before every test card is finished. Buying while testing is the only way to get scale by 2027, and it aligns with how the program is structured in increments. The result will look more like a software product that ships a minimal viable set of combat tasks and then updates often, a pattern mirrored in open architecture meets the AI battlefield, rather than a polished, everything-on-Day-1 fighter.

Autonomy you can brief to a commander

Autonomy is the leverage point, but it is also the safety question. The military uses “safety cases” to prove that complex systems behave within acceptable risk bounds. For CCA, that means a layered approach:

- Bounded autonomy. The aircraft operates within a defined envelope for speed, altitude, maneuver load, and weapon employment. Out-of-bounds conditions trigger conservative behaviors such as disengage and return.

- Separation of concerns. A flight safety module is kept distinct from mission autonomy. If mission logic locks up during a complex sensor fusion task, a simple guardian keeps the jet upright, deconflicted, and predictable.

- Predictable handoffs. The human on the loop can always pause or reshape a behavior, and the aircraft must respond in a set, time-bounded way. Think of it as a reliable brake pedal that feels the same every time.

- Evidence over assertions. Each new behavior is flown in scripted scenarios that mimic real threats. The autonomy team builds a library of “claims, arguments, and evidence” that shows why a behavior is safe enough for the next step.

Rules of Engagement, or ROE, add another layer. Early CCAs will not get permission to fire a missile on their own. More likely, they will extend a crewed fighter’s reach by carrying extra weapons and recommending shots that a human must approve. Picture a formation lead in an F-35 or F-15EX seeing two targets sorted by risk and geometry on a display, with a proposed plan from two CCAs: one to illuminate with a radar burst, the other to launch. The pilot taps approve and the plan executes. Over time, the autonomy can be authorized to handle more of the timing, while the human keeps ownership of the decision to employ lethal force.

There is also the gray area between peacetime intercepts and high-end combat. ROE will specify how close a CCA can approach aircraft from non-hostile nations, how it signals its presence, and when it must yield deconfliction to a manned aircraft. That keeps pilots in the loop for the kinds of dynamic cross-border encounters that can escalate if misread.

The human machine team in Pacific terms

Why does this matter for the Indo-Pacific? Distances. A fighter sortie over water is a long chain of tankers, relays, sensors, and timing. The enemy will try to cut that chain by jamming links, targeting tankers, and forcing our fighters to burn fuel dodging threats. CCAs can absorb some of that strain, reinforcing a strategy of attritable scale similar to mass arrives in the Pacific.

- Mass at the edge. Send a four-ship of crewed fighters with four CCAs each, and you have tripled the number of apertures scanning and the number of weapons that can be placed at a useful point in space. If one CCA is lost or damaged, the pilot is alive and the rest of the formation stays on plan.

- Sensing without broadcasting. A CCA can run passive sensors forward and sideways while the crewed fighter stays at lower emissions. That helps form a picture of the battlespace without announcing where the pilot is.

- Elastic tactics. In a long-range fight, timelines stretch and compress. CCAs can sprint forward to sanitize a corridor, then fall back and refuel, while crewed fighters pace themselves for the main engagement.

Imagine a vignette. A pair of F-35s are tasked to sanitize a corridor for a bomber cell. Four CCAs push 100 miles ahead in loose line abreast. Two run passive infrared search to sniff for hot spots that look like aircraft at medium altitude. One drags a decoy to provoke radar turn-ons. Another carries a wideband receiver and records the enemy’s jamming patterns. The F-35s watch a single fused track picture rather than four separate feeds. When a cluster of hostile tracks begins to gate in from the north, the lead assigns two CCAs to fire long-range shots on command and a third to jam the target radar. The jamming start time, power, and beamshape are chosen by the autonomy based on an onboard model of the threat radar. The pilot approves the plan. The missiles ripple. The bomber cell moves through on time.

The point is not that this is flashy. It is that it is repeatable, with clear roles for the pilot and the autonomy, and that it scales to a theater where distance punishes every mistake.

Payloads that matter now

One of the most important choices in the next year will be payloads and weapons. CCA Increment 1 should avoid the temptation to do everything and instead chase three categories that give the most return per pound and per watt:

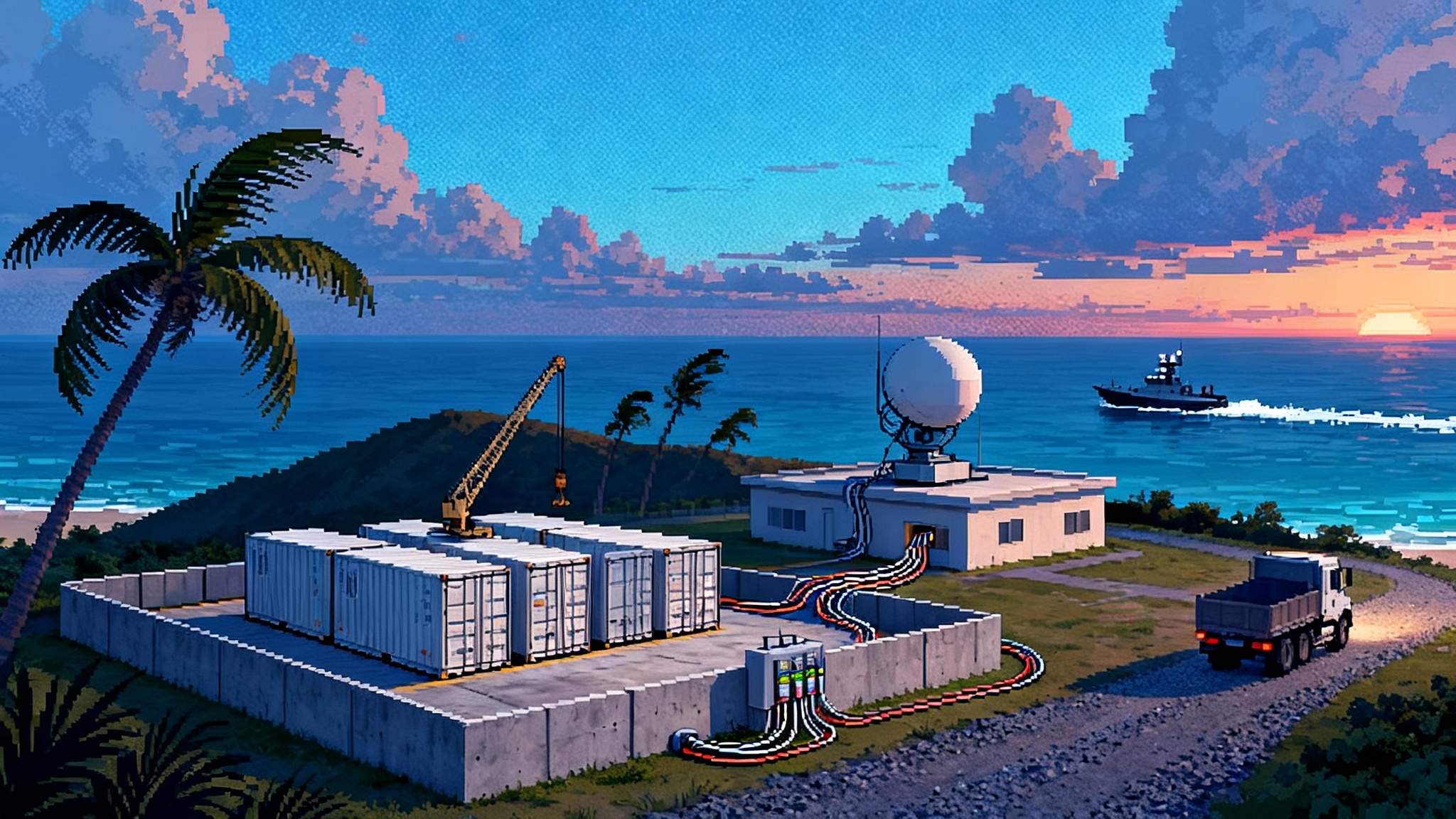

- Electronic Warfare, or EW. Stand-in jamming pays off fast in the Pacific. The candidate airframes are big enough for effective antennas and power modules yet cheap enough to send forward. A smart play is to field a modular EW suite with swappable cards. That lets teams adapt to unique threat radars on short cycles and lets the same airframe perform escort jamming on Monday and radar decoy work on Wednesday.

- Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance, or ISR. Passive infrared search and track, wideband electronic support, and compact synthetic aperture radar give crews the targeting fidelity they need without broadcasting. If the autonomy can filter and pre-correlate the data, the cockpit workload stays under control.

- Air to air weapons. Early CCAs should carry the same beyond visual range missiles as their crewed teammates. That makes logistics simple and gives commanders a straightforward way to translate autonomy into more shots. The human approves the employment, the CCA handles the timing and energy management.

Other payloads will matter in later spirals. Stand-in attack against surface threats, communications relay, and offboard decoys are all promising. But the near-term CCA should favor payloads that add reach and resilience to the air dominance mission.

The hard part: making autonomy explain itself

Trust is built on explanations that a pilot can read before stepping to the jet and after landing. That means CCA developers need to invest in two simple but powerful tools.

- Pre-briefed behaviors. For each mission type, publish a short playbook that shows how the autonomy prioritizes tasks, how it reacts when a link drops, and what it does when two tasks conflict. Use concrete if-then examples, not generalities. If datalink A drops for more than N seconds, the CCA will move to waypoint B at airspeed C and hold D miles off the formation until it sees any of these three rejoin cues.

- Debrief narratives. After landing, provide a timeline that explains the top five decisions the autonomy made, with reasons. The pilot does not need to see weights of every neural network node. They need to see that the aircraft chose a jamming technique because the threat radar’s pulse repetition interval matched a known mode, and that the CCA then shifted because the radar changed modes.

These explanations, paired with a disciplined safety case, turn a black box into a teammate.

How a software-first industrial base bends the fighter cost curve

CCA is also a stress test of how the U.S. defense industrial base is changing. Two shifts matter most.

- Software-defined combat power. The winning teams are treating aircraft as hardware that carries software-defined capability. Instead of designing a bespoke, closed system that changes slowly, they are building open mission systems, containerized autonomy, and developer pipelines that push updates every few weeks. That does not remove the need for airworthiness rigor. It decouples flight safety from mission software so that a new electronic attack technique or sensor fusion algorithm can be fielded without re-testing the wing spar.

- New contracting and factory models. The department is mixing competition with speed, using a vendor pool, rapid options, and production decisions that keep multiple teams honest. Meanwhile, industry is investing in flexible factories that can scale. Anduril’s new Ohio campus, described as Arsenal-1, is an example of how defense firms are trying to make airframes and autonomy at a pace more like commercial electronics than traditional fighters, with the goal of lowering the unit price as volumes increase.

If this works, it bends the fighter cost curve in three ways. First, pay for the airframe once, pay for new mission software many times. Second, buy more small increments of capability rather than one giant leap that takes a decade. Third, keep competition alive for payloads and autonomy stacks even after the first production lot is awarded.

Five concrete shifts to watch between now and late 2027

-

First weapons separations from a CCA. This is the moment when the aircraft moves from a loyal wingman metaphor to a true shooter. Expect captive carry first, then live fire with the human approving release.

-

Reliable ops in bad networks. The decisive technical metric is useful performance when bandwidth is low and latency is high. A good sign will be CCAs completing tasks after a link drop without inducing aircraft separation risk or timeline busts for the human formation lead.

-

Cross-team payloads. If an Anduril aircraft flies a General Atomics electronic support payload or vice versa, the program is living up to its open-architecture promise. That matters more than any slide about modularity.

-

Training pipelines that treat autonomy as a crew member. Look for tactics schoolhouses to publish syllabi that include supervising two or more CCAs, with standards for when to grant more autonomy and how to debrief it. That will show commanders that the concept is maturing into doctrine.

-

Early buys that lock in capacity. To be credible in the Pacific by 2027, the service will likely place initial production orders before every test card is done. The key is to pair those buys with aggressive reliability growth and clear retrofit plans so the early jets do not become orphans.

What changes now for industry, operators, and Congress

-

For industry: Deliver explanations, not just performance. Put pre-brief and debrief tools into the hands of pilots now. Ship autonomy updates on a steady cadence. Demonstrate payload swaps across company lines. Design for a clear cost per effect metric and show how software increments lower that cost over time.

-

For operators: Build tactics that treat CCAs as numbers first and exquisite sensors second. In practice, that means using them to create mismatches in geometry and timing, not only to collect better pictures. Write ROE that scale. Start with positive human approval for lethal actions and then expand authority only as safety cases earn it.

-

For Congress: Protect the competition and the increments. Fund early buys with retrofit lines and do not force a premature common design. The biggest risk to cost control is locking into one supplier and one payload set too soon.

The bottom line

In one week, CCA moved from a promise to a program with two jets in the air. The next two years will decide whether that promise scales into tactics and production. If developers keep the software factory humming, if commanders demand autonomy that can explain itself, and if the department buys early and iterates fast, the fighter force can add affordable mass without losing control. That is how you turn a headline flight test into a durable shift in airpower.