Charybdis Changes the Math for U.S. Offshore Wind Buildout

America’s first Jones Act wind turbine installation vessel is now working in Virginia. Charybdis reduces idle days, cuts costs, and de-risks schedules. Here is what it unlocks through 2028, what still blocks progress, and the moves that compound the win.

The milestone that resets the baseline

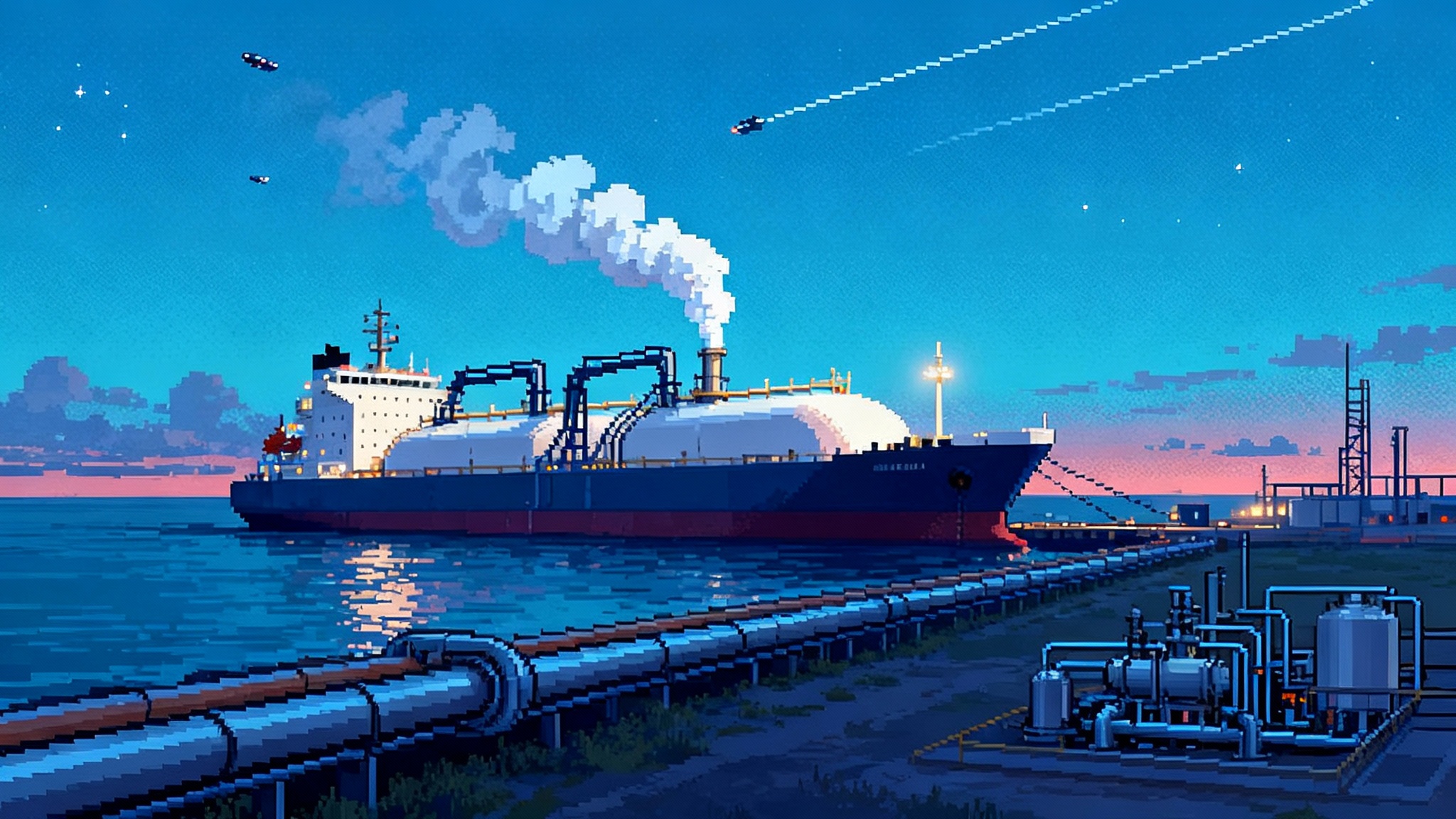

In mid September 2025, the first U.S. built and U.S. flagged wind turbine installation vessel, known as a WTIV, reached its new home port at Portsmouth Marine Terminal and prepared to start work on Dominion Energy’s Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project. It was a quiet photograph that landed like a thunderclap. A five year bet on American heavy industry had crossed from drawings and press statements into a working asset. The vessel’s name is Charybdis, and its arrival is not just an industrial curiosity. It is the turning of a page for how the country plans, prices, and delivers offshore wind. See the reporting in Charybdis arrives in Virginia.

To understand why this is big, start with the Jones Act, the century old law that says only U.S. built, U.S. owned, and U.S. flagged vessels can carry goods between U.S. points. An offshore wind farm is a U.S. point for that law. Until now, developers had to charter foreign heavy lift jackups to do the actual lifting offshore, then ferry components out on U.S. barges and tugs. That feeder choreography worked, but it added interfaces, standby time, and weather risk. A single miscue in that chain could idle a very expensive crane and crew.

Charybdis collapses that risk stack. It can load towers, nacelles, and blades directly at a U.S. port, sail to site, jack up on its legs, and install. Fewer handoffs, fewer waits, fewer days where a perfect forecast still produces no lifts because a barge or tug is an hour late or a pilot window is missed. When every lift is a small construction project and every day offshore is priced like a professional sports team salary, these avoided delays add up fast.

How one domestic installer changes the math

Think about a 14 megawatt class turbine. It is a giant set of components, each the size of a house or a building. A nacelle that weighs hundreds of tons. Three blades longer than a football field. Tower sections that are as wide as a city bus is long. To install one turbine you have a sequence of lifts and connections that can stretch across many hours. Multiply by 176 turbines in Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind, and then multiply again by the weather clock that governs jackups.

Before Charybdis, a U.S. project that relied on a foreign installation vessel typically used feeder barges that met the jackup at sea. If a feeder missed a tide window by two hours, the jackup often lost most of a day because of crew work rules, visibility limits, or current. If a barge could not safely bring a blade across a quartering sea, everything slackened until morning. Even with expert teams, the risk of mismatch was baked in.

Give that same project a domestic WTIV and three things shift immediately:

- Fewer idle days. Every fifth turbine, losing one extra day to handoffs can quietly add a week of delay every month. Over a build season that alone becomes months.

- Lower mobilization and standby costs. The vessel mobilizes once from a nearby port, not from a transatlantic yard, and it waits less for components offshore.

- A smoother learning curve. One owner operator and one crew run the same vessel for months in the same port and sea state. Lessons compound instead of resetting with each contractor change.

The rough economics are easy to visualize. Imagine a thirty month construction timeline built around eight workable months per year for heavy lifts. If a domestic WTIV trims just five percent of unproductive time, that can save dozens of offshore days. Saving even a few weeks reduces interest during construction, frees up other marine spreads sooner, and pulls the first power date forward. A pulled forward first power date changes net present value, which can change bidding behavior in the next auction or power offtake round.

There is also a hidden safety and productivity dividend. When the same crew cycles the same motion hundreds of times from the same port, they get faster and safer. This speed matters as the grid confronts new demand; see our take on the U.S. grid playbook for AI demand.

The counter signal that proves the point

A week before this article’s deadline, another headline hit. Maersk Offshore Wind moved to terminate a nearly completed wind turbine installation vessel at Singapore based builder Seatrium that had been aimed at the Empire Wind project. The contract value was reported at roughly 475 million dollars, and the shipyard said the hull was 98.9 percent complete. Whatever the legal outcome, the message to planners is stark. If U.S. projects depend on foreign builds, on foreign yards, and on a world market that can turn on a dime, then schedule certainty is always rented, never owned. See the report in Maersk cancels a WTIV contract.

This is not a triumphal story about domestic versus foreign. It is a pragmatic story about control of critical path assets. When an entire build sequence hinges on one or two specialized vessels, owning one inside your own legal and capital system is a structural risk reducer.

What this unlocks between 2026 and 2028

Bigger turbines, steadier seasons, and a Gulf Coast to Mid Atlantic supply chain that behaves more like an industry and less like a rotating pop up shop. Here is what to expect if owners, ports, and policymakers capitalize on the moment.

-

Turbine size steps without chaos. Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind is set around a 14 megawatt class machine. The world market is already pushing toward 15 megawatt and beyond, and blades now exceed one hundred meters. A domestic WTIV that is built for high hook heights and heavy nacelles gives developers a viable path to modest uprates in late stage design without rethinking the entire marine strategy. The key is incrementalism. With one known vessel and crew in the rotation, upgrades can be staged by campaign rather than by entire project redesign.

-

More reliable build seasons. The Atlantic does not care about our schedules, but it does reward repetition. A homeport installation vessel based in Virginia or the Mid Atlantic can work a longer shoulder season in local conditions. The feeder ports can sequence arrivals to that rhythm. As the crew refines limits in sea state, current, and visibility, everyone upstream calibrates to a realistic but slightly wider window of workable days.

-

A Gulf Coast to Mid Atlantic flywheel. Texas and Louisiana shipyards have built oil and gas liftboats, platform jackets, and marine spreads for decades. Charybdis was built in Brownsville. That matters. When a yard delivers a complex vessel like this, it builds a team, a vendor list, and a muscle memory. Those capabilities travel from hull projects into component handling frames, blade racks, and the small but critical steel that lets ports turn faster. The ripple runs up the coast. Ports in Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, and New York can specify equipment with Gulf Coast suppliers who now understand the offshore wind duty cycle. For broader Gulf context, see our Gulf LNG whiplash analysis.

-

Better crew pipelines. A single domestic installation vessel becomes a training platform. Mariners step up from tugs and crew transfer boats into jackup operations. Rigging teams graduate from port lifts to offshore lifts. That human capital is the most scalable resource of all, and it is the quiet secret behind every industrial surge.

The bottlenecks that still bite

A single ship cannot carry a national buildout. The United States needs a handful of installation vessels to hit any credible run rate. It also needs a few other pieces that are less photogenic but just as decisive.

-

More WTIVs, not just one. A realistic path to five or six major projects per year requires multiple jackups with different strengths. At least one optimized for next generation hub heights and blade lengths. At least one flexible unit that can work in shallower fields or handle maintenance and repowering. Diversity in hulls is insurance against a single outage or regulatory pause upending a season.

-

Port upgrades that match the hardware. Heavy lift quays need higher bearing capacities than most existing berths. Think tens of tons per square meter, not low single digits. Yards need laydown areas for blades that are longer than a city block, with road geometry or barge slips that let them move without damage. Ports also need component sequencing software that is more like airline ops than warehouse ops, because a slip in one blade move can idle a crane worth hundreds of thousands of dollars per day.

-

Component logistics that keep pace. Monopiles are now so large that floating them alongside is often safer than rolling them by road. Nacelles cannot hit potholes. Blades hate tight turns and gusts. That means more waterborne moves, better blade cradles, and standard grillages that fit multiple hulls without custom welding for every voyage.

-

Subsea cable and substation capacity. Turbines grab headlines, but cables and offshore substations often set the pace. The country needs more cable lay spreads and repair capacity and more companies that can assemble, test, and install high voltage substations at sea.

-

Grid and interconnection. A farm that reaches mechanical completion is not a power plant until it can export at full load. Upgrades onshore must be timed to offshore milestones, not lag them by a year. For why timing the grid matters, see the FERC 1920-A transmission rules.

Practical moves that compound the gains

We can turn one breakthrough into a durable cost curve if market makers and policymakers act on the mechanics rather than the rhetoric. Here are targeted steps that add up.

-

Publish rolling, binding installation calendars. States and offtakers should require developers to publish six quarter lookahead installation calendars that include vessel names, port calls, and component campaign windows. Tie a small share of the offtake price to on time calendar updates. This creates shared visibility and lets ports and suppliers staff to the cycle rather than playing catch up.

-

Use ship finance tools we already have. The U.S. Maritime Administration can expand Title XI loan guarantees for specialized offshore wind vessels with faster underwriting and explicit eligibility for installation and cable ships. Pair that with accelerated tax depreciation for vessels and for heavy lift port gear that serves offshore wind. The combination lowers capital cost enough to justify a second or third hull.

-

Create port super user agreements. Port authorities should offer multi season, multi project berthing and laydown rights to installation consortia in exchange for guaranteed throughput and training commitments. The goal is to make ports into predictable factories, not one off construction sites.

-

Standardize the small steel. Developers and fabricators should publish open specifications for blade racks, tower frames, and grillages. If a rack that fits Charybdis also fits a second vessel without cutting torches, setup time shrinks and safety improves.

-

Adopt inflation indexed offtakes by default. The last two years showed what happens when fixed price contracts meet volatile input costs. Indexation for a narrow set of marine and materials costs should be standard, with transparent formulas that de risk vessel builders and port investors. The reward for ratepayers is more bidders and real competition on execution, not just on paper prices.

-

Fund maritime workforce ladders. Community colleges and maritime academies can add installation specific rigging, jacking system operations, and high voltage offshore modules. Public funds should follow seat time on vessels like Charybdis, with apprenticeships that convert into credentials recognized by multiple owners.

-

Stand up a national offshore wind operations center. Treat the next five years like an air traffic control problem. A public private center can integrate weather models, vessel positions, port schedules, and cable lay windows. With better shared situational awareness, everyone reduces avoidable waits.

What this means for developers and suppliers right now

If you develop projects, prioritize installation certainty in your bid strategy. It has a larger compound effect on cost and schedule than another round of supplier discounts. Offer longer charters to domestic vessels to anchor a second hull order. Build your construction calendar around the vessel and port pair you can actually secure, then select turbine models and foundation details that fit that pair rather than chasing the last percentage point of nameplate capacity.

If you run a port, invest in the unglamorous pieces that installation crews notice in the first hour. Bearings and fendering that accept heavy hulls. Blade storage that aligns with safe turn radii. Lighting and security that let crews work efficiently at dawn and dusk. Software that assigns scarce laydown space to actual lift sequences rather than first come, first served yard maps.

If you are a supplier on the Gulf Coast, lean into modularity. Design blade racks and transport saddles that can be adapted to different blade lengths with bolt on extensions. Build steel that can survive a year outdoors in a corrosive environment without rework. Offer rental pools for gear that projects do not want to own forever, like self powered blade turners and tower section dollies.

If you are a policymaker, set a two year rhythm for auctions and for port grants, and keep to it. Developers can plan around a cadence even if prices float. Investors finance ships and cranes when the calendar is credible.

The tipping point from talk to tonnage

Every industry has a moment when one long delayed asset shows up and the narrative shifts. Charybdis is that moment for U.S. offshore wind. It does not solve every bottleneck and it does not immunize the sector from global shocks. It does something more basic. It puts the core lift in U.S. hands and U.S. waters, with a crew that will get better every week it sails.

There will be setbacks. Contracts will be canceled and rewritten. Storms will take workable days away. Components will arrive late, and welders will fix what models missed. None of that changes the baseline. The country now has a domestic installation vessel that can run a multi year campaign from a domestic port, under domestic law, with domestic crews.

That is why the math changes. Timelines compress. Risk premiums shrink. Suppliers invest with more confidence. A second vessel goes from speculative to financeable. Ports plan for steady seasons, not one off surges. And by the time the 2026 to 2028 window closes, the dull, welcome reality of steel in the water will have replaced most of the breathless headlines. That is the kind of progress you can see from shore and feel in your power bill.