One-shot LDL Editing Arrives: PCSK9’s 2025 Inflection

In 2025, PCSK9 base editing crossed from moonshot to near-term prevention. FDA milestones, first human data, and Lilly's move for Verve point to single-infusion cholesterol control.

The news: a prevention moment five decades in the making

The idea that we could edit cholesterol at its genetic thermostat sounded like science fiction. In April 2025, it turned into something more concrete. Verve Therapeutics reported initial Heart-2 data showing that a single intravenous infusion of VERVE-102, an in vivo base editing medicine targeting the PCSK9 gene, produced dose-dependent reductions in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. In the 0.6 mg per kg cohort, the mean drop in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol was more than half, with a maximum reduction approaching seventy percent. These early results sit alongside two pivotal regulatory milestones. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration cleared the Investigational New Drug application in March 2025, and on April 11, 2025 granted Fast Track designation for VERVE-102. That combination moved base editing from a moonshot to a near-term prevention strategy that U.S. cardiology sites can now evaluate.

Then came a corporate shock wave. Eli Lilly agreed to acquire Verve, betting that a one-time genetic intervention can redefine cardiovascular prevention. The headline price, structured with upfront cash and milestone value, framed the deal as a strategic leap from chronic adherence-challenged pills to what many now call a one-shot vaccine for atherosclerosis. The analogy communicates the point: one visit rather than a lifetime of refills. Coverage of the agreement captured how mainstream this is becoming, including the Lilly to acquire Verve story that helped set the tone for the year.

How a single letter edit tames cholesterol

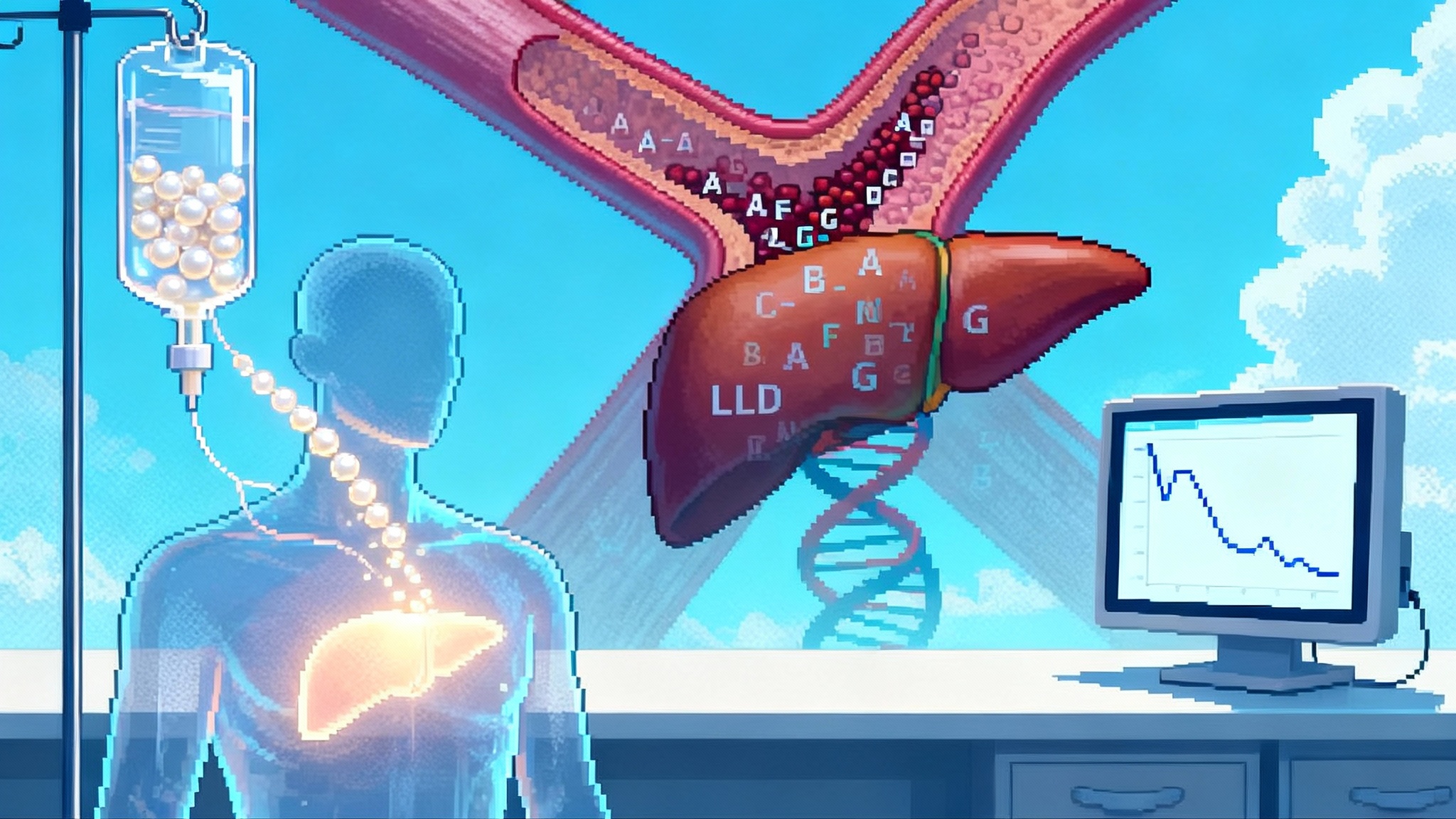

Think of the PCSK9 gene as a thermostat that tells the liver how many low-density lipoprotein receptors to keep on its surface. Those receptors are like drain grates that clear cholesterol particles from the blood. When PCSK9 levels are high, the thermostat removes those grates and the drain clogs. When PCSK9 is turned off, more grates stay in place, and the blood clears cholesterol much faster.

VERVE-102 uses base editing, which is closer to spell-check than to cutting and pasting. Instead of making a double-strand break in DNA, an adenine base editor swaps a single A for a G at a precise spot in the PCSK9 gene. That single typo makes the gene stop working. Because liver cells are long-lived and constantly filtering blood, the effect can be durable. The edit is delivered to the liver in a lipid nanoparticle, a tiny fat-like bubble that carries the messenger RNA for the editor and the guide RNA that steers it to PCSK9. Verve's second-generation particles include a GalNAc targeting ligand so that the package finds liver cells efficiently through two natural receptors. The pitch is simple to grasp: fix the thermostat once, then let biology do the rest.

Why 2025 was the inflection point

Several forces converged this year.

- Regulatory green lights in the United States. The Food and Drug Administration accepted Verve's plan, allowing U.S. sites to open, and then granted Fast Track. Those steps mean faster feedback loops, easier dialogue on trial design, and the possibility of accelerated pathways if efficacy and safety hold up.

- Human data that look like the genetic ideal. For decades, people born with natural loss-of-function variants in PCSK9 have had very low low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and very low rates of heart disease. Drug developers proved the target pharmacologically with antibodies and small interfering RNA that lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol by roughly 50 to 60 percent. Now base editing in humans is tracing that same curve, and doing it with one dose. The gene-silencing arc parallels our coverage of one-dose siRNA for Lp(a).

- A big company signal. Lilly's agreement to buy Verve was more than balance sheet maneuvering. It was a statement that one-and-done prevention can be a primary-care reality, not just a boutique procedure.

Durability: from months to years to a lifetime

Durability drives the economics and the clinical value of genetic prevention. A statin works as long as you take it. Miss doses and the benefit fades. A base edit persists as long as the edited liver cells do. Early human experience is encouraging. In Verve's earlier PCSK9 program, the highest-dose participant maintained large reductions in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol out to at least eighteen months after a single infusion. The 2025 VERVE-102 readout strengthens the case by showing consistent dose-response across cohorts and by connecting total RNA dose to pharmacodynamic effect, a practical lever for clinicians.

Mechanistically, this staying power makes sense. Hepatocytes do not turn over quickly, and the liver is a regenerative organ that tends to copy the edit as cells divide. Clinically, the key question is not whether the edit fades in months. It is whether it remains strong across years and whether that long tail keeps cardiovascular risk low without cumulative harms. The final dose-escalation data and the planned Phase 2 trial should clarify the multi-year slope.

Safety and off-targets: the questions that matter

Base editing avoids making double-strand breaks, which reduces some risks seen with other editing approaches. But the field still watches for off-target edits at both DNA and RNA, for transient toxicities from lipid nanoparticles, and for extreme lowering of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol that might cause unexpected effects.

The initial VERVE-102 dataset is important on all three fronts. First, there were no treatment-related serious adverse events reported across the first cohorts, and there were no clinically significant changes in alanine aminotransferase or platelets. That matters because transient liver enzyme spikes and platelet drops can appear after lipid nanoparticle delivery. Second, the edit itself is designed to mimic a loss-of-function state that many people carry naturally without obvious health problems, which sets a favorable prior for safety. Third, unlike double-strand break editors, base editors operate as precise chemical erasers, which helps confine their action to intended sites when the guide and editor are well engineered.

The cautious view is still appropriate. Rare off-target edits might not surface until larger trials or longer follow-up. Immune reactions to the editor protein or to the nanoparticle components must remain on the watchlist. And while very low levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol have looked safe in trials of injectable PCSK9 blockers, this will be tested anew in a one-time gene edit. The right posture is active surveillance, pre-specified stopping rules, and transparent reporting of any signal that emerges as dosing expands.

Who is likely to get it first

Early access will not be for everyone. Expect a stepwise path.

- Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. These are patients with a genetic tendency to run high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol from birth, often with early coronary disease. Many still struggle to reach targets even on a statin, ezetimibe, and a PCSK9 blocker. A once-per-lifetime reduction could be transformational for this group.

- Premature coronary artery disease with persistently high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. The Heart-2 trial includes adults with early-onset coronary disease who need deep and durable lowering. This mirrors the population where the prevention payoff is largest.

- Statin-intolerant or adherence-challenged patients at very high risk. A one-time therapy may be attractive for those who cannot tolerate standard therapy or who have a history of inconsistent use and recurrent events.

Broader primary prevention will wait for Phase 2 and Phase 3 data, for clarity on long-term safety, and for payment models that fit primary care.

Compressing lifetime exposure: why this changes risk, not just today's number

Cardiovascular risk does not come from a single blood draw, it comes from the area under the curve of exposure over decades. Picture a bathtub with the faucet partially open. Statins and injectables ask you to turn the handle down every day or every few weeks. A one-and-done PCSK9 edit fixes the faucet position. If the faucet is almost off from age 50 onward, the tub fills much more slowly. That lower cumulative exposure should reduce the rate of plaque growth, stabilize existing plaques, and cut the likelihood of heart attacks and strokes across a long horizon. For health systems, this reframes prevention around early, durable interventions rather than constant reminders and refills. It aligns with other step-change approaches we have covered, such as one-shot OA gene therapy and gene therapy restored hearing.

How VERVE-102 compares with today's tools

- Oral statins. Inexpensive and effective when taken, but real-world adherence is mixed and a meaningful subset of patients cannot tolerate them at doses needed for aggressive targets. Therapy must be continued for life.

- Injectable antibodies that block PCSK9. Strong and reliable low-density lipoprotein cholesterol reductions. Dosing is every two to four weeks. Costs have fallen, but access hurdles and adherence can still be challenges.

- Small interfering RNA that silences PCSK9. Twice-yearly dosing removes many adherence problems. It is a powerful option for long-term management.

- Base editing of PCSK9. One infusion, then nothing else to do if the edit sticks and remains safe over years. The open questions are long-term safety, durability across a broad population, and how to price and pay for a single course that delivers benefits over decades.

The practical takeaway: for patients who need deep, durable lowering and for systems tired of chasing adherence, the one-time edit could become the preferred strategy once pivotal safety and efficacy readouts arrive.

Economics and access: the price of a lifetime of prevention

One-time therapies challenge old playbooks. Payers spread the cost of chronic drugs over many years and often across different insurers as people change plans. A one-time genetic edit concentrates the cost up front while the benefit accrues gradually. That makes outcomes-based contracts likely. Health systems and manufacturers can tie payment to sustained low-density lipoprotein cholesterol reduction at twelve and twenty-four months, to reductions in cardiac events, or to a hybrid that begins with biomarker thresholds and graduates to event-based rebates as data matur e.

Hospitals will also need operational readiness. These are outpatient infusions that require a gene therapy workflow: patient selection, genetic counseling, labs before and after dosing, and long-term follow-up registries. Health plans can prepare by building high-risk rosters today, flagging people with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or very high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol despite guideline-directed therapy. When access opens, those lists become the first wave of candidates.

What to watch next

- Final dose-escalation data and longer follow-up from Heart-2. We need to see how the curves look beyond the first months, whether dose-response holds up, and whether editing percentages correlate tightly with cholesterol outcomes across more participants.

- The start of U.S. Phase 2. U.S. site activation will put community cardiology, academic centers, and payers into the same room. Expect a tighter conversation on inclusion criteria, monitoring, and practical logistics.

- Manufacturing scale and lot-to-lot consistency. Lipid nanoparticles and messenger RNA manufacturing matured during the pandemic, but gene editing reagents have added complexity. Consistency at commercial scale will affect both safety and reliability.

- The rest of the pipeline. Verve has programs that aim to edit ANGPTL3 and LPA. If PCSK9 base editing clears the bar, the playbook carries over, and the idea of multiplexed lifetime lipid control becomes plausible.

What clinicians and health systems can do now

- Build a registry of patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia and premature coronary artery disease who remain above target low-density lipoprotein cholesterol despite guideline-directed therapy. Include intolerance flags, prior adverse effects, and baseline imaging if available.

- Standardize shared decision-making materials that explain base editing in plain language. Use visuals that show the thermostat analogy, explain irreversibility, and outline follow-up schedules.

- Define monitoring plans. Pre-specify labs at day 1, week 1, weeks 4, 12, and 24 after dosing to watch liver enzymes, platelets, and lipid panels, with clear escalation pathways for any signal.

- Engage payers and pharmacy and therapeutics committees early. Agree on biomarker thresholds that trigger payment milestones and on criteria for referral to infusion centers.

- Track patient-reported outcomes. Fatigue, muscle symptoms, and anxiety about one-time edits matter. Systematic collection will make the value story stronger.

The bigger bet: healthspan through earlier, deeper prevention

The most important implication of one-time low-density lipoprotein cholesterol editing is not the lab result. It is the possibility of compressing decades of exposure into a safer range, then keeping it there without the daily friction of pills. If that holds, cardiology shifts from rescue to maintenance, from chasing numbers to setting them once. The burden of heart attacks and revascularizations is unlikely to vanish, but the balance could move toward fewer events at older ages and more years lived without symptomatic disease.

The bottom line

This year marked the moment when in vivo base editing for cardiovascular prevention moved from "if" to "when." The science behind VERVE-102 is mechanistically clean, the early human data are consistent with what genetics promised, and the Food and Drug Administration's stance plus Lilly's bid make it clear that mainstream adoption is the goal. The next two years will be about durability, breadth of safety across larger populations, and the health system plumbing that makes a one-time edit practical. If those pieces fall into place, turning down the cholesterol thermostat once could become one of medicine's simplest and most powerful ways to extend healthy years of life.